This is Part 2 of a series of 4 posts I am writing on the formation of our landscape, that is the landscape around the River Mole in Surrey. The first part can be found here: https://themolestory.com/2023/01/31/making-mole-hills-out-of-mountains-the-formation-of-the-mole-and-the-weald/

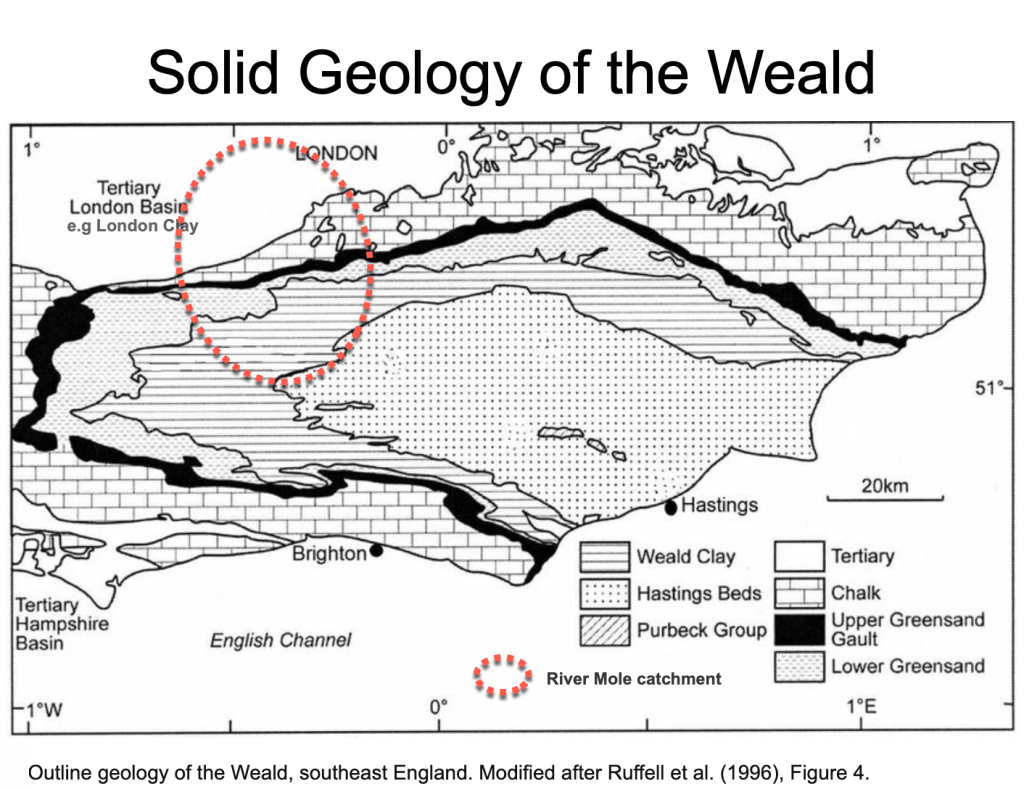

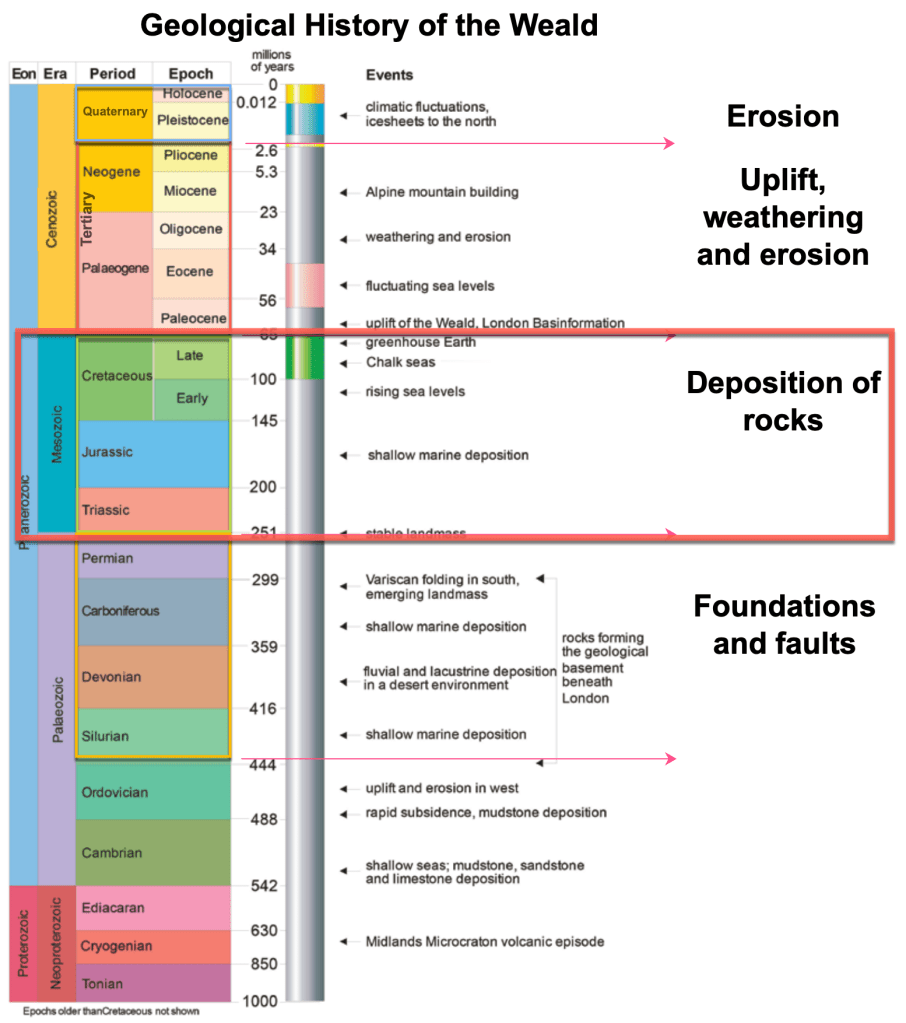

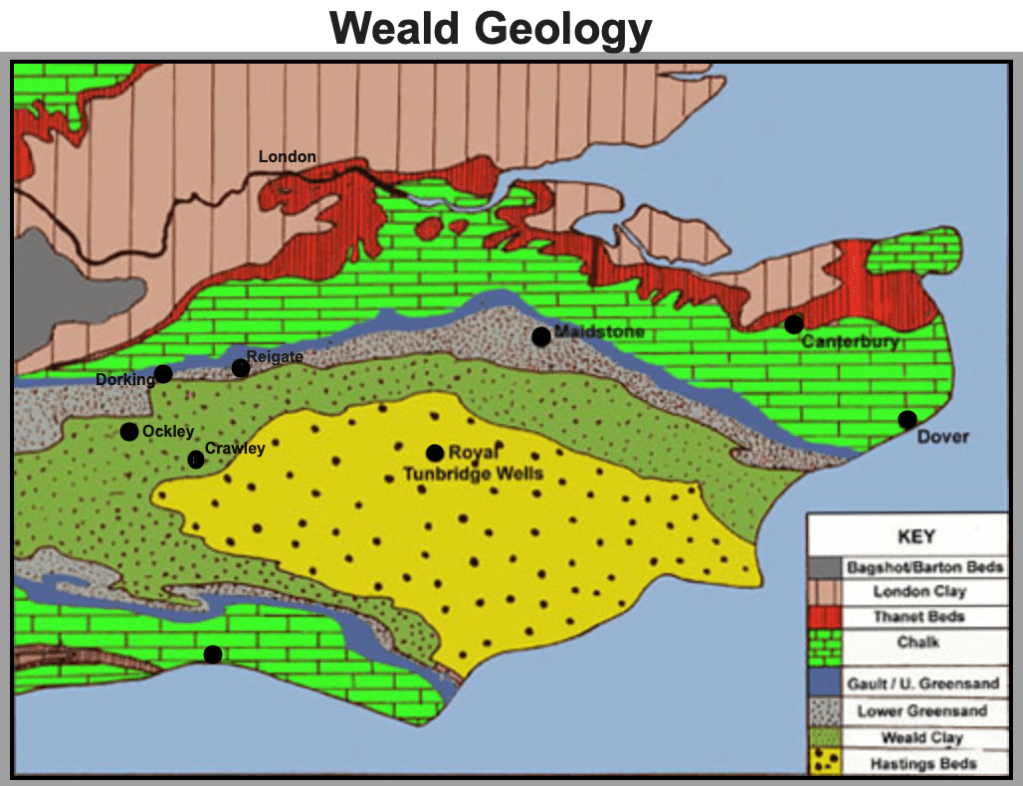

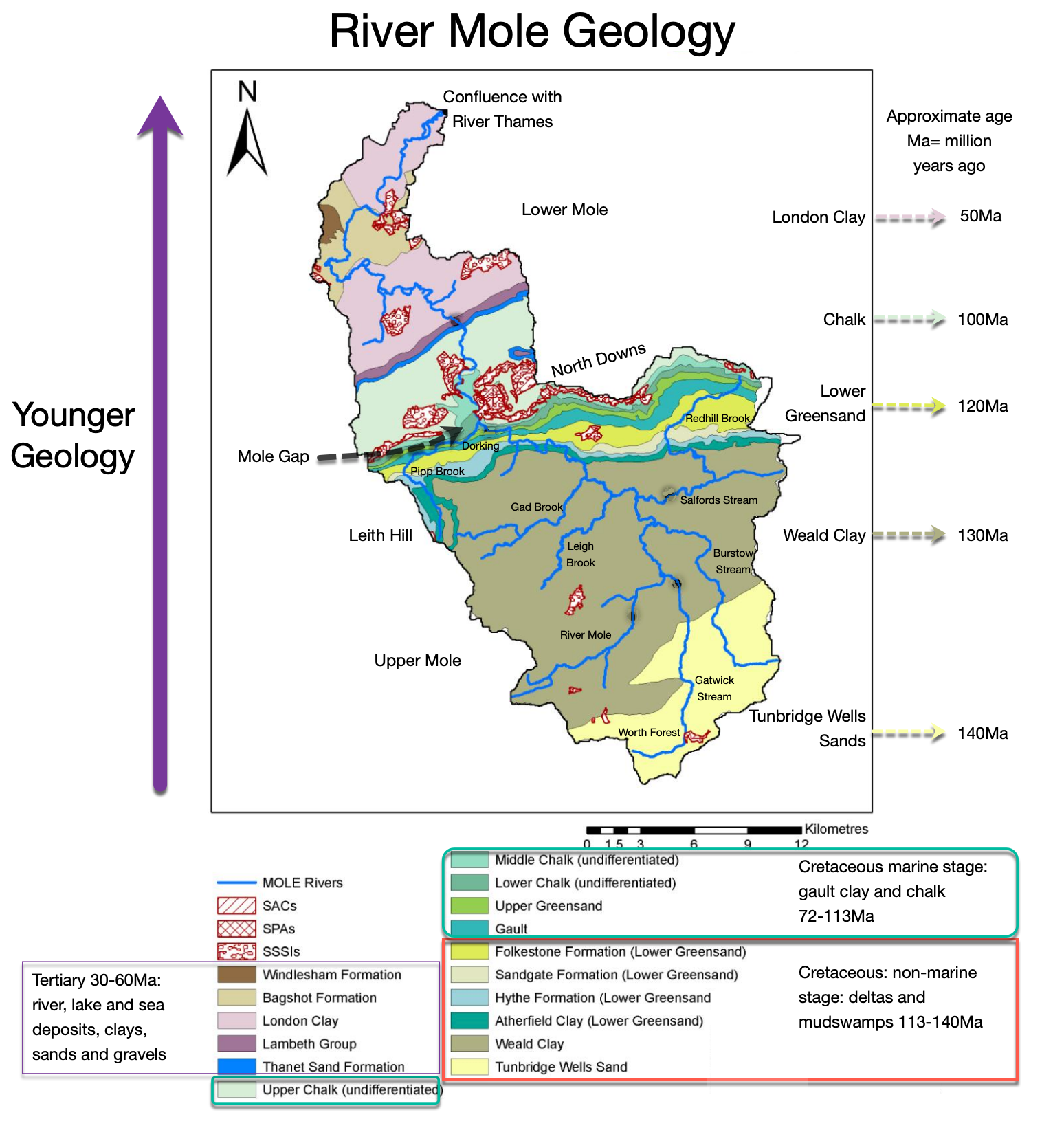

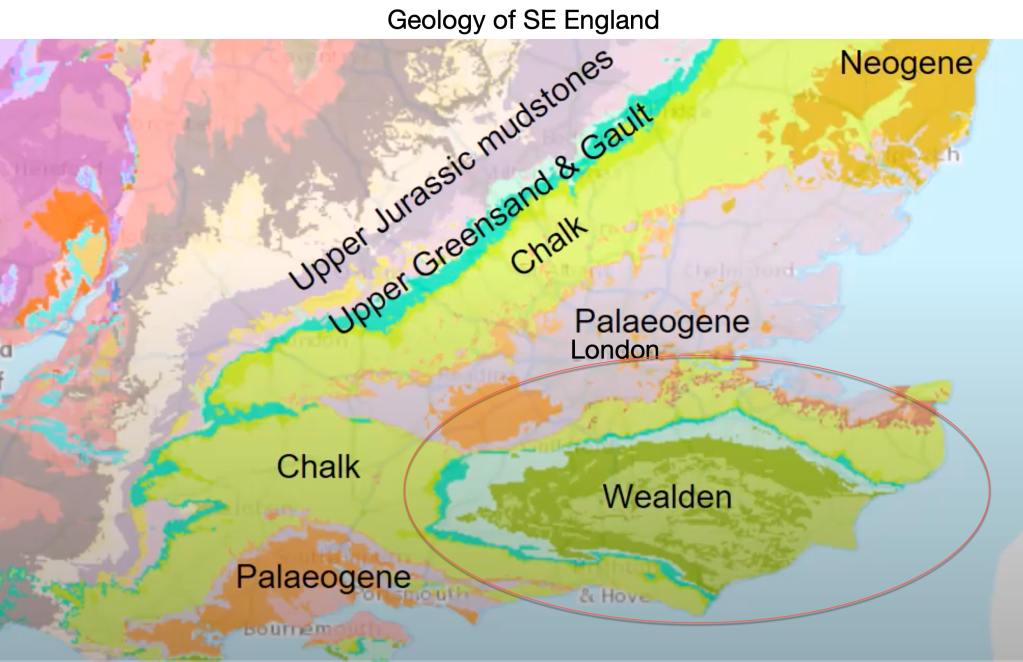

The Mesozoic era lasted an immense 200 million years. Between 250 and 66 million years ago, sediment from the erosion of surrounding land was deposited in a depression or trough. The sediments accumulated into an immense thickness of rock several kilometres deep. These rocks formed the building blocks of the Weald and the Downs. The latter half of the Mesozoic, called the Cretaceous Period, is responsible for almost all the solid bedrock geology now found in the Upper Mole Catchment and seen on geology maps. The map below shows the groups of rocks laid down in the Mesozoic which are now found at the surface.

The long period of time during the Mesozoic witnessed huge thicknesses of debris accumulating in deltas, lakes and seas. Each layer of sediment reflected the character of the environment from which it was derived.

Weald Clay, for example, is found across a wide swathe of the Upper Mole Basin from north of the A264 to the foot of the North Downs. It is formed from the eroded remains of a hilly landmass which existed to the west of the Weald trough called Cornubia. Large rivers swept debris from Cornubia into a Tropical mud-swamp between 130-125 Ma. The clay pits around our area are famous for dinosaur discoveries buried in the clay from that period of the Cretaceous.

Baryonix, for example, was discovered in the clay at Smokejack clay pit in Ockley. The picture below shows the clay pit with fossil hunters working away. On a trip with palaeontologists to a Weald Clay pit, David Bangs, in his excellent book “The Land of the Brighton Line, A Field Guide to the Middle Sussex and South East Surrey Weald” remarked:

Looking down on the pin sized figures working away at its base..I realised that those layers represented only a small part of the Wealden Clay sequence. I got a real sense of the immensity of the time and geological processes that went into the making of our soft countryside of little woods and fields and slow streams”

David Bangs The Land of the Brighton Line. A field guide to the Middle Sussex and South East Surrey Weald 2018

Over 5 million years, a 500m layer of clay accumulated. This is a rather pedestrian rate of accumulation and results from a slow rate of erosion from surrounding land. The slow erosion rate was probably the result of a dense cover of tropical forest covering the land and slowing weathering and erosion to a snail’s pace. There was a lot of time, so no hurry!

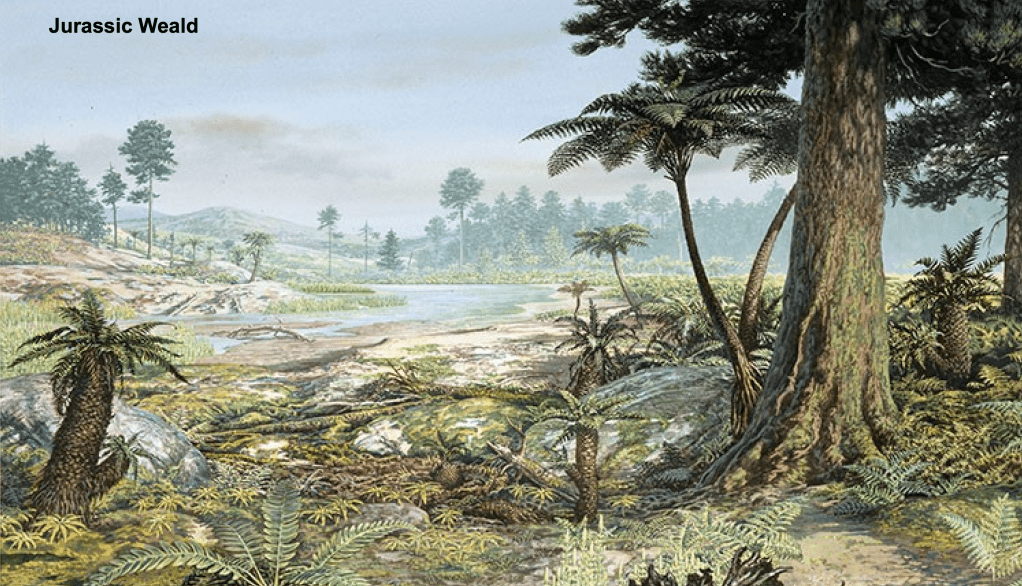

During this period England was located in the mid-latitudes and experienced a highly variable climate of alternating searingly hot dry seasons with forest fires and baked ground and stormy wet seasons with flash floods which created lakes in a floodplain environment. The resultant ecosystem was highly diverse, supporting a vast number of aquatic and land-dwelling organisms

https://ukafh.com/tag/weald-clay/

Let’s take our own time to see how the Mesozoic has shaped our landscape:

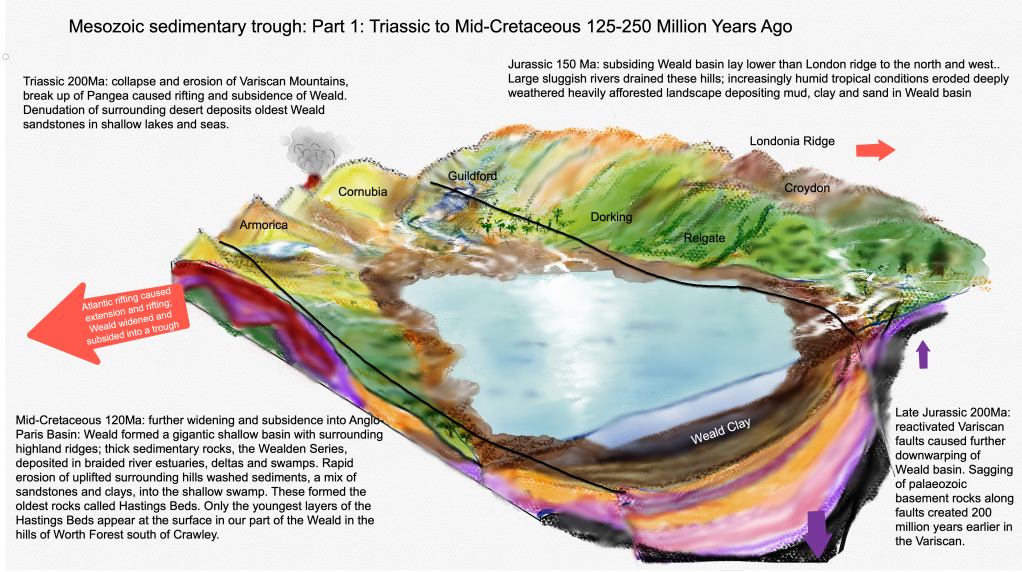

At the start of the Mesozoic, around 250 million years ago, the Variscan Mountains were collapsing, partly due to rifting forces as Pangea broke up and the Atlantic started to widen, and also due to erosion in the hot, arid Triassic climate.

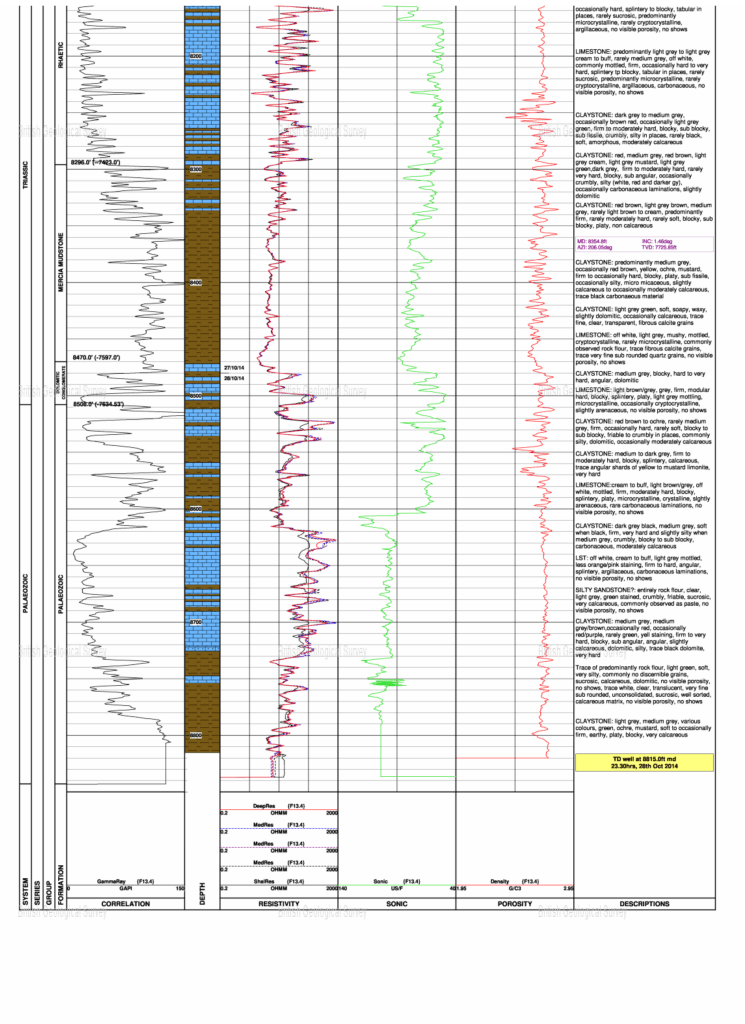

Britain at the time sat in an arid belt around 30N of the Equator. By the Late Triassic the Weald existed as an arid depression as extensional forces caused it to subside while the stable London Platform to the north sustained higher ground known as the Wales-Brabant Massif, from which eroded debris entered the basin via large rivers. The Triassic and Upper Jurassic sandstones probably deposited as shore-line sand bars, are the earliest sedimentary rocks of the Mesozoic period found in our region but are now buried under 2-3 kilometres of younger rocks, so you wont find any at the surface!

From around 200 million years ago, in the increasingly humid Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, the Weald subsided further into a large depositional trough along the axes of the already extremely ancient Variscan faults. Sea levels also rose.

During the Jurassic Period, the site of the future Weald was eventually submerged by the sea and a sedimentary basin developed.

D.K.C.Jones The Weald

A. Goudie and P. Migoń (eds.), Landscapes and Landforms of England and Wales, World Geomorphological Landscapes

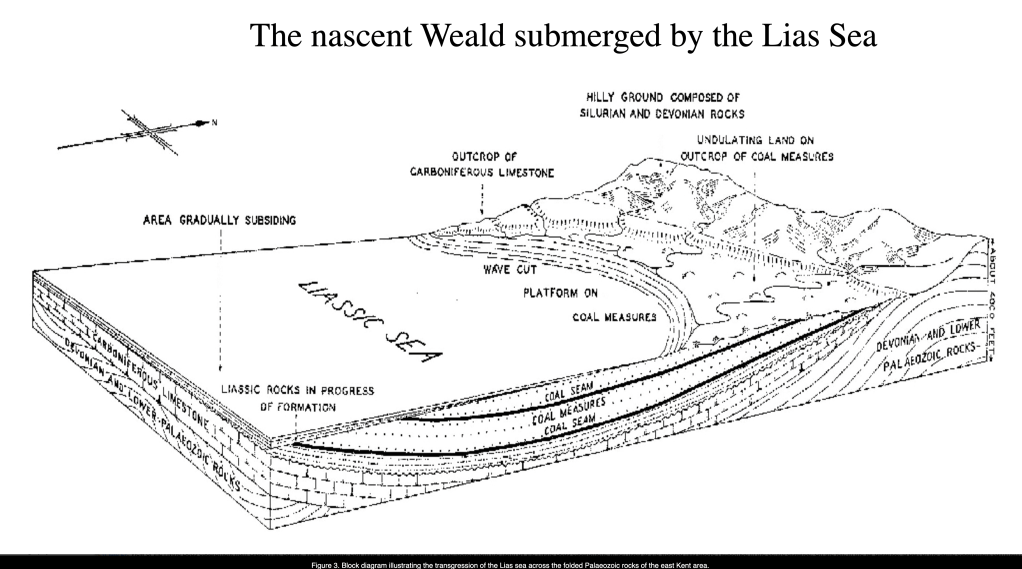

Extensional tectonic forces further widened the basin, reactivating the Variscan faults causing the Palaeozoic floor to sag under the burden of accumulating sediments washed in by large rivers draining from the surrounding humid tropical landscape. The “Lias Sea” was formed.

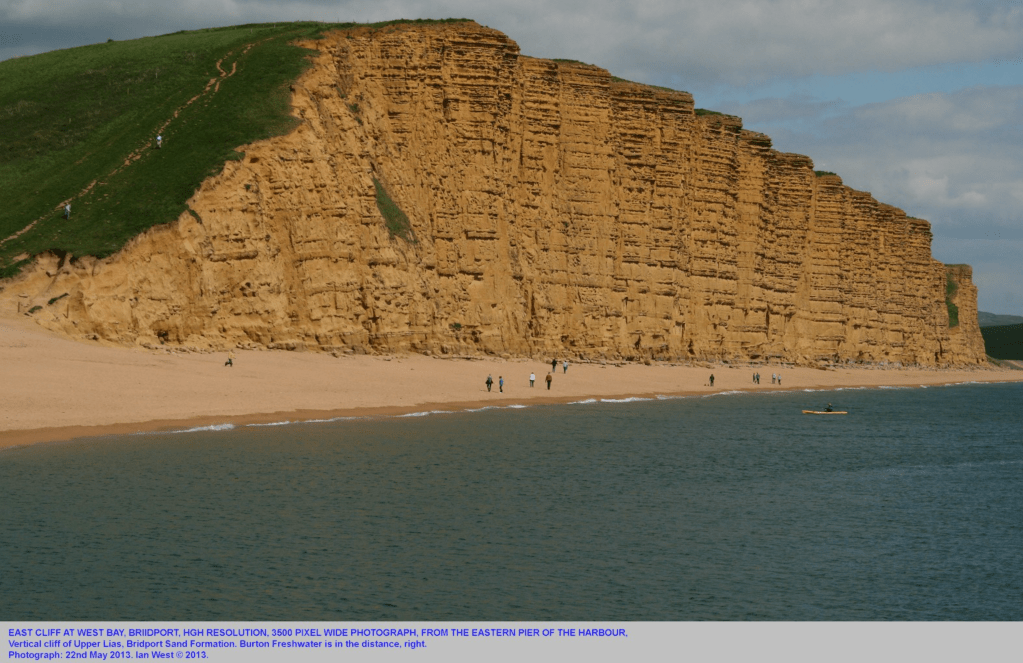

Tropical conditions on surrounding land chemically weathered rocks producing a mantle of fine muds and clays which were readily eroded and washed out. The debris was deposited in the sea to form rocks like mudstone and clay. These rocks are known as the Lias Group and include mudstones, clays and layered limestones called shale. These occur at the surface in Dorset where they can be seen in cliffs at West Bay but occur several kilometers underground in the Weald. Lias is the source rock for the Weald Basin petroleum and gas system.

Occasionally, relative uplift of the surrounding land to the north, known as the London Platform, caused rivers to erode more vigorously into the landscape, a process called rejuvenation. This deposited coarser sands and gravels in the basin. Over time, the basin subsided into a deeper tropical sea, like the Bahamas now, when Jurassic limestone was laid down.

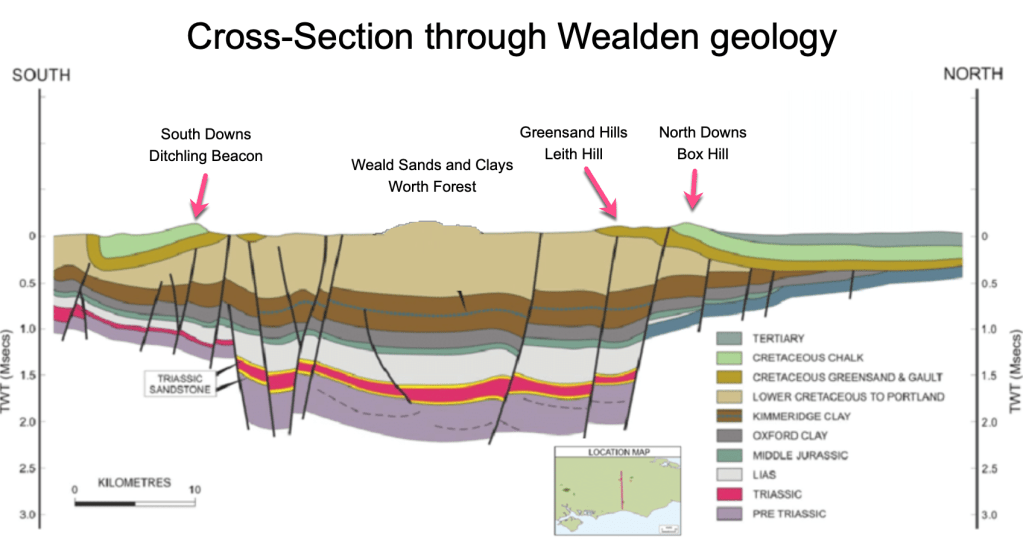

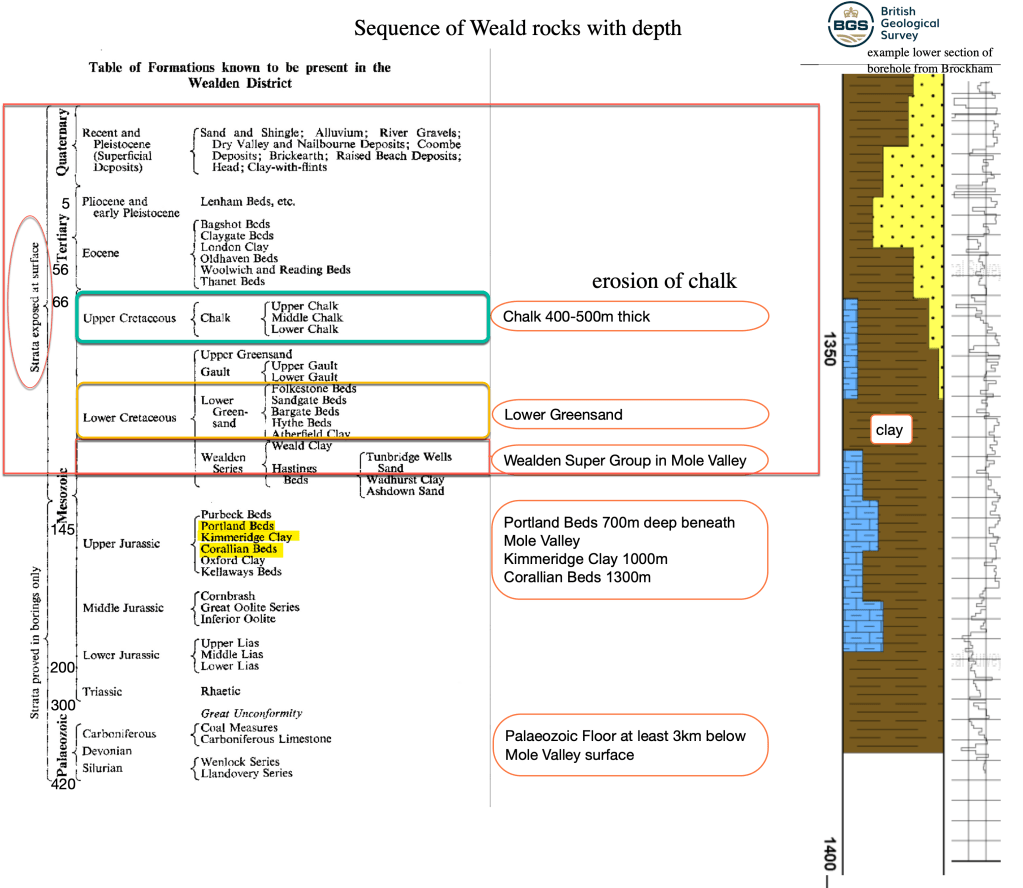

Today, bore holes drilled at Horsehill, Brockham and Norwood Hill have discovered Jurassic Purbeck Limestone at 450m below the surface, Portland limestone at 500m, Kimmeridge Clay at 700m and Corallian Sandstone over 1100m deep. The oldest Jurassic layers extend below 1800m deep while Triassic mudstones appear around 2400m. The Palaeozoic Floor starts at over 2500m deep beneath the Mole Valley at Horsehill.

In total over 1500m of Jurassic sediments accumulated in the basin causing a downward “sag” in the Palaeozoic rocks and reactivation of the pre-existing Variscan faults.

The Cretaceous turned out to be a critical period for forming the rocks that built the structure of the landscape we see today. In the Early Cretaceous, around 135 million years ago, the Lias Sea retreated and the Weald became a freshwater lake. This lowland was part of the Anglo-Paris Basin probably occupied by a sea further south, open to the Tethys Ocean somewhere in central France. A lake shoreline ran north of the Weald beneath a ridge roughly where London is now. Two large river systems eroding this ridge deposited Wealden sands and clays and, later, Lower Greensand across swampy deltas, possibly like Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela now.

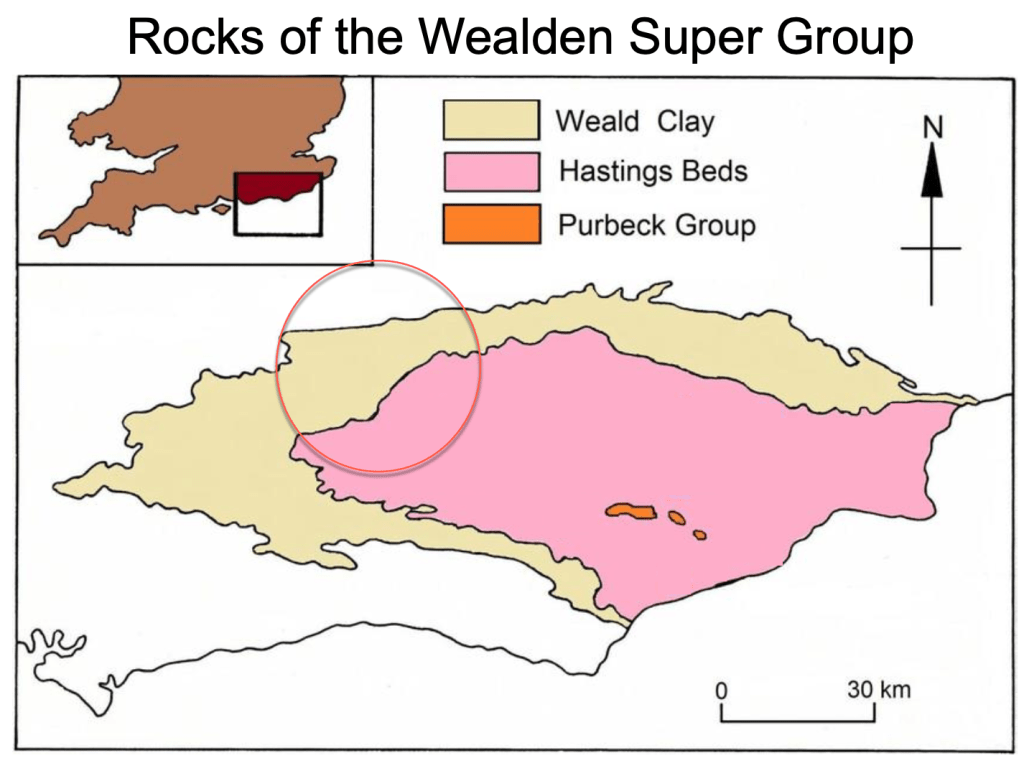

The early Cretaceous rocks are the oldest exposed rocks now found in the Central Weald and are collectively known as Hastings Beds. They were exposed at the surface only because the younger overlying layers of the Weald anticline were eroded after uplift in the Tertiary.

To expose the oldest Hastings Beds, hundreds of metres of overlying younger rocks had to be eroded away, a process called denudation. We will find out how this happened in the next part!

In the Mole catchment the Hastings Beds include Tunbridge Wells Sand and Weald Clay. Collectively they are known as the Wealden Super-Group.

Tunbridge Wells Sand forms the hills south of Crawley around Worth Forest and the Weald Clay. The Weald Clay is more easily eroded and so forms the extensive lowland part of the Upper Mole around Gatwick. Weald Clay was laid down as debris from the erosion of the London ridge.

The clay was deposited by sluggish rivers meandering around a giant mud swamp for 7 million years! This was ample time for the clay to accumulate into incredible thicknesses, up to 500m thick in the Mole Valley.

At the end of the Weald Clay times, around 126 million years ago, the land barrier with the sea was breached and the Weald Basin became an arm of the ocean into which Lower Greensand was deposited. Some uplift of the land occurred during this period so rivers eroded more energetically and deposited coarser sands in the shallow bay.

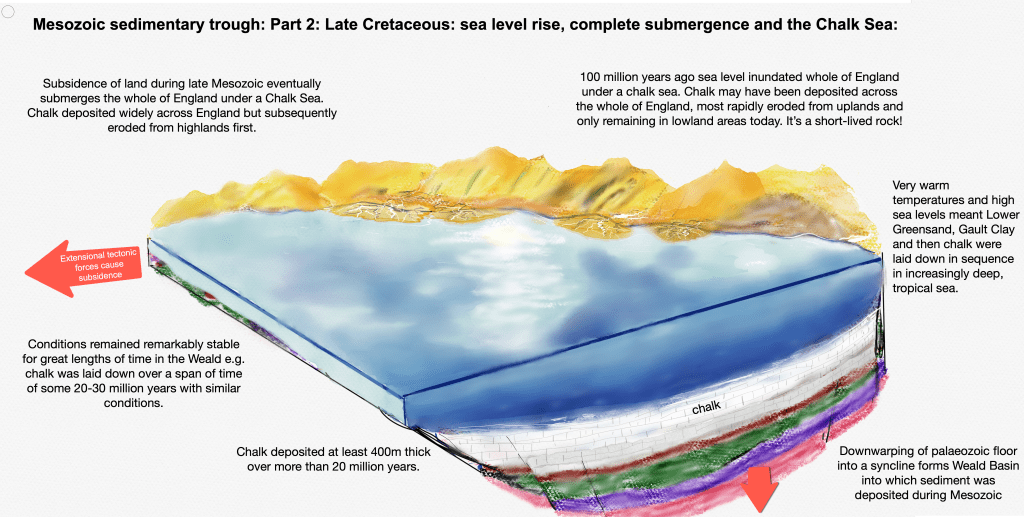

The Late Cretaceous is thought to have had a ‘super greenhouse’ climate, produced by large amounts of submarine and continental volcanic activity that pumped huge volumes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, melting ice and raising sea levels and creating the conditions for prolific life to form in tropical oceans. These conditions were ideal for the deposition of our most iconic geology in the Mole Catchment and the South East: Chalk!

The height of the Chalk Downs is a visible reminder of the enormous length of time it took to deposit the rock. It also shows the vast amount of carbon sequestered in those white rocks.

The Late Cretaceous, from about 100 million to 65 million years ago, was a period of ‘Greenhouse Earth’, with a much warmer global climate than at the present, and globally very high sea levels, possibly the highest of the past 500 million years

London’s Foundations 2012

The Chalk Sea 100Ma

Between 70 and 100 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous, sea level rose to inundate much of England, apart from the highest tops, beneath a deep tropical sea. This is known as a marine transgression. The immense Chalk Sea extended as far east as Kazakhstan where chalk mountains can still be seen today.

At first, the sea would have planed-off the remnants of any hilly landscapes of the Jurassic forming a flat layer onto which, first Gault Clay and then Chalk, were laid down. The shorelines were swept back to the uplands of Wales and Northern England. As the downward movement of the land continued the sea level rose and a tropical sea, a bit like the Red Sea today, took shape. With land increasingly distant, very little input of eroded debris entered the sea, except occasional clouds of volcanic ash now found as fine layers in Chalk.

The tropical Chalk Sea teemed with life including microscopic shelly creatures called coccoliths. These creatures were eaten by shrimps and their excreta rained onto the sea floor and created a carbonate-rich sludge, compressing over time to form chalk. So Chalk is quite literally white marine poo! The Cretaceous Chalk Sea lasted over 20 million years during which time a 400-500m thick layer of chalk was laid down over the Weald.

The Weald was covered by between 400 and 500 m of chalk during

Hansen et al.: A model for the evolution of the Weald Basin p111

the Upper Cretaceous, which extended across the

whole of southern Britain, northern France, and beyond.

Conditions remaining stable for this long to form such a widespread thickness of pure white limestone seems extraordinary. Since then, most of the chalk has been comprehensively removed by erosion and what we see now on the Downs and Chilterns are only scrappy remnants of what was originally laid down. Even today, Chalk extends under the Channel and emerges again in Northern France.

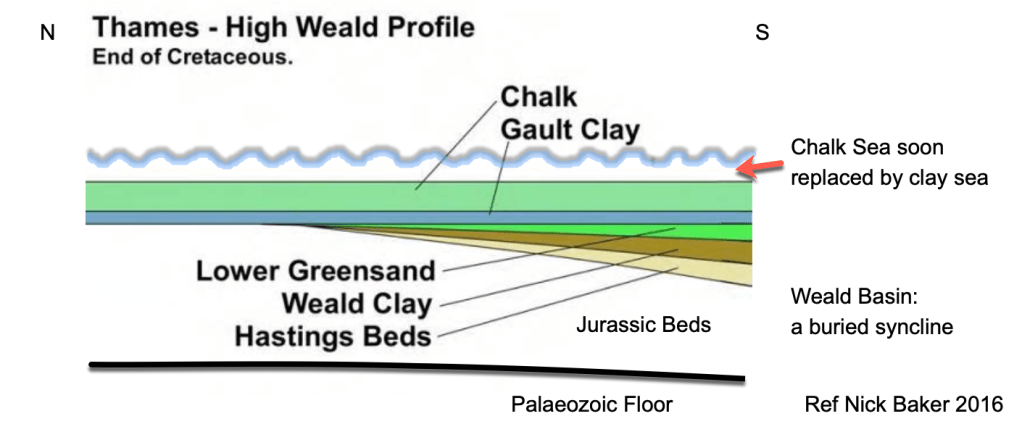

By the end of the Cretaceous period, the raw materials were in place from which the current Wealden landscape is now built. From the deepest sandstones of the Hastings Beds, the soft Weald Clays and youngest Lower Greensand and Chalk, these layers total some 1500m thick of Mesozoic rocks that were “draped”, layer by layer, over the ancient Palaeozoic floor in a vast basin.

Schematically, the layers looked something like the cross-section above with the youngest Chalk at the top and progressively older rocks deeper down the bulk of which had been deposited in the Weald Basin, a downfold known as a syncline, shown on the right hand side of the diagram. The resulting rocks laid down during the Mesozoic are shown below. These are the oldest rocks found at the surface in our part of the Weald and form the backbone of the River Mole catchment landscape.

The familiar horseshoe rings of geology in the Wealden area shows the oldest rocks in the centre of the Weald and the youngest on the outside. In my next post, we will explore how these rocks, deposited in thick layers with the oldest rocks deeply buried under kilometres of more recent rocks at the surface, came to be exhumed in this horseshoe shape.

Thank you for reading my post which covered the formation of the rocks we now find in the Mole Catchment and form our landscape. I hope you enjoyed it. The next post will be on the uplift in the Tertiary.

References:

History of the major rivers of southern Britain during the Tertiary Compiled by Philip Gibbard & John Lewin https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/tertiaryrivers/

D K C Jones London School of Economics: The Weald p73-101 A. Goudie and P. Migoń (eds.), Landscapes and Landforms of England and Wales, World Geomorphological Landscapes,

Nick Baker 2016: The Problem of Post-Cretaceous Drift Deposits https://mfms.org.uk/pages/pdf/Muck%20notes.pdf

Pliocene beach under London https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2018/03/19/workers-discover-ancient-coastline-in-west-london/

Hansen, D.L., Blundell, D.J. & Nielsen, S.B. 2002–12–02. A Model for the evolution of the Weald Basin. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, Vol. 49, pp. 109–118. Copenhagen.

South East Research Framework Resource Assessment and Research Agenda for Geology and Environmental Background (2018 with additions in 2019)Geological and Environmental Background Martin Bates and Jane Corcoran

Migoń, P. & Goudie A., Pre-Quaternary geomorphological history and geoheritage of Britain. Quaestiones Geographicae 31(1), Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań 2012 https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.2478/v10117-012-0004-x

British Geological Survey: Geology Viewer and Lexicon https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/?_ga=2.7037298.1327190817.1675929737-1868444071.1675929737

Mole Valley Geology Society https://www.mvgs.org.uk/geomorphology

How Britain Became and Island: Lecture with Professor Phil Gibbard. https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/englishchannelformation/

Variscan Orogeny https://variscancoast.co.uk/variscan-orogeny

The Geology of the Weald. William Topley FGS. Published HMSO 1874

Relative Land-Sea-Level Changes in Southeastern England during the Pleistocene, Vol. 272, No. 1221, A Discussion on Problems Associated with the Subsidence of Southeastern England (May 4, 1972), pp. 87-98 (12 pages) R. G. West Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences

Leave a reply to Making Mole Hills out of Mountains: Part 3 – The Mole Story Cancel reply