Part 1: The Palaeozoic Floor

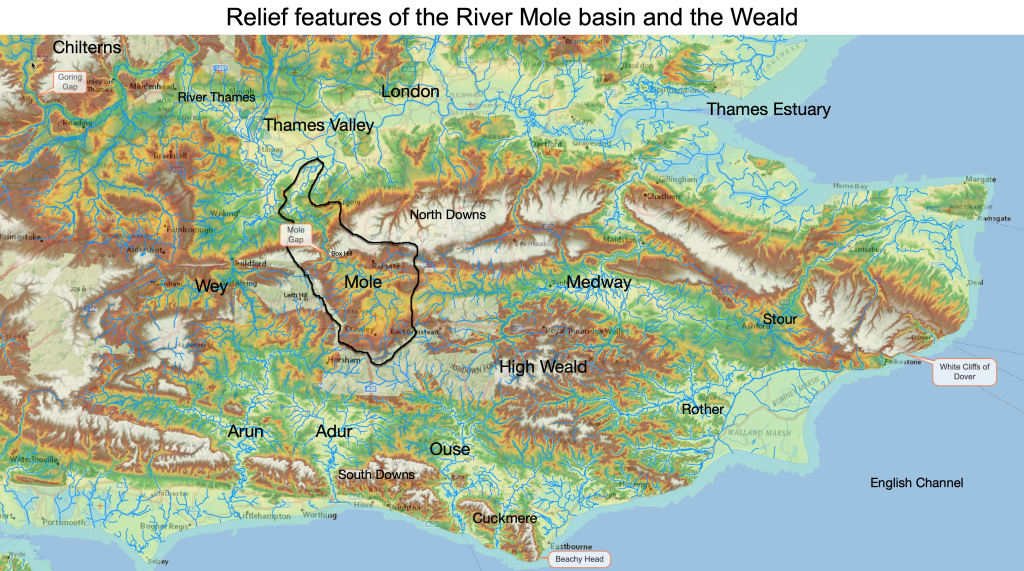

This is the epic story of how the landscape of the River Mole catchment has been formed. Geographically we are dealing with the Downs, the Weald, the Mole Gap and the London Basin to the confluence with the River Thames.

It is an immense topic spanning 400 million years of Earth and Mole history. It’s so long that I’ve split it into these four parts. I’ll post each part as I finish writing it.

This post is Part 1 which covers a review of the current landscape, a history of some theories of formation, and a dive into deep Earth history to discover the rocky foundations of our corner of the Weald. Other posts will follow soon!

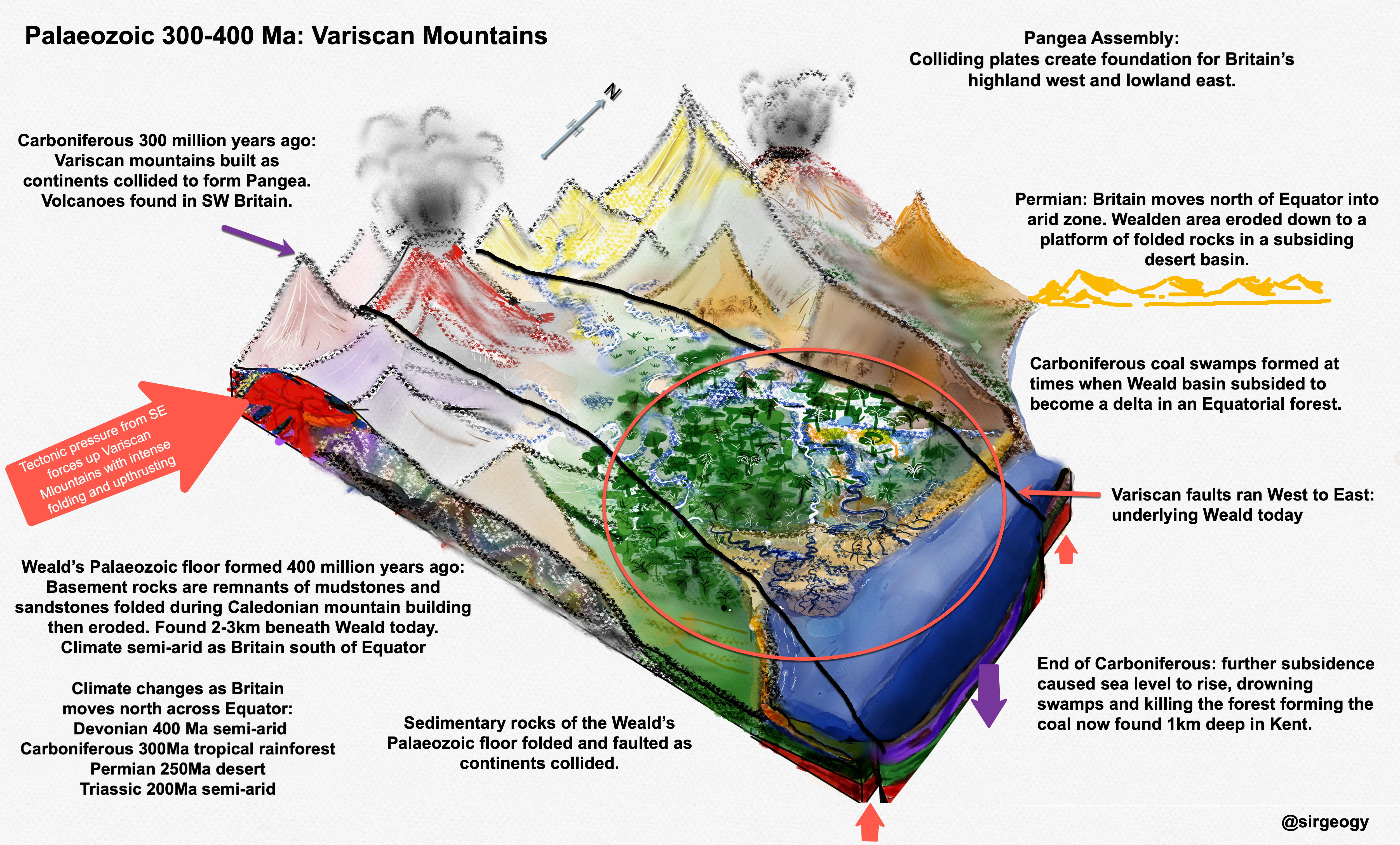

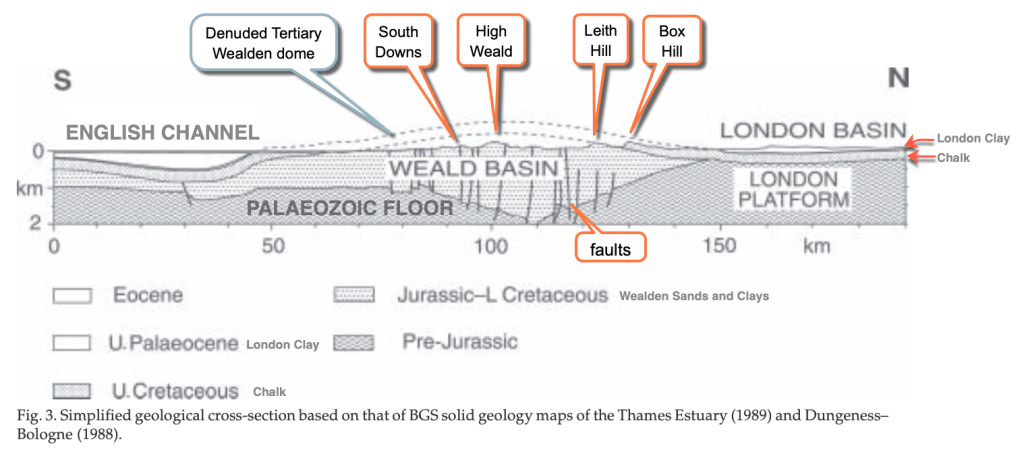

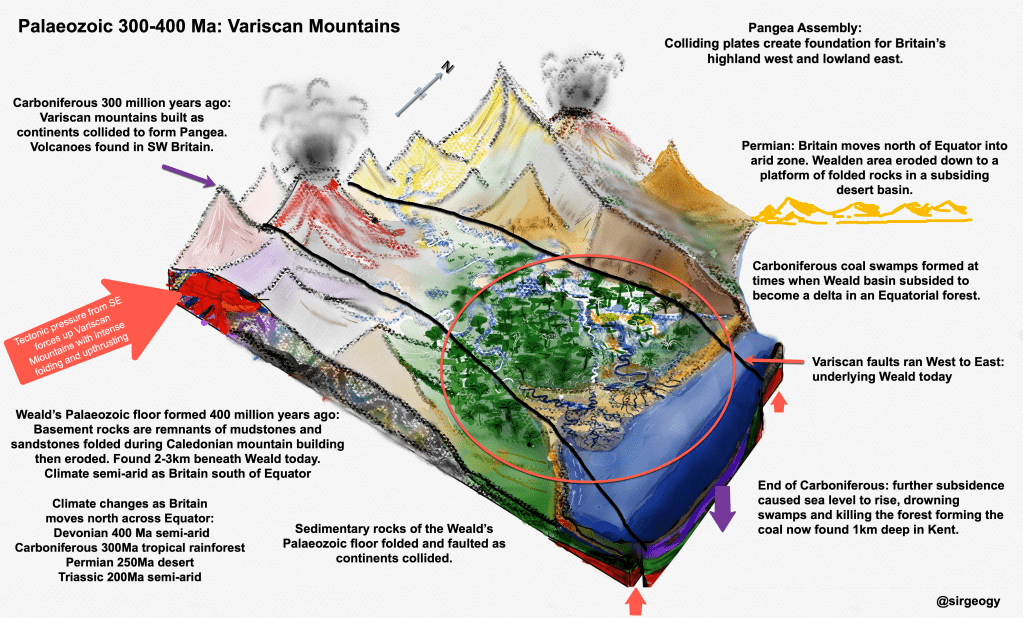

Part 1: The Palaeozoic Floor: the first part of the Weald story starts when our piece of the Earth’s crust, somewhere in the Southern Tropics, was on the edge of a fold mountain range called the Variscan Mountains which left faults crucial to how the Weald landscape formed 200 million years later. The very oldest rocks beneath the Weald are now buried kilometres beneath our feet and include the coal found in Kent, itself 3000 feet down. These oldest, deepest rocks form what geologists call the “Palaeozoic Floor” or basement.

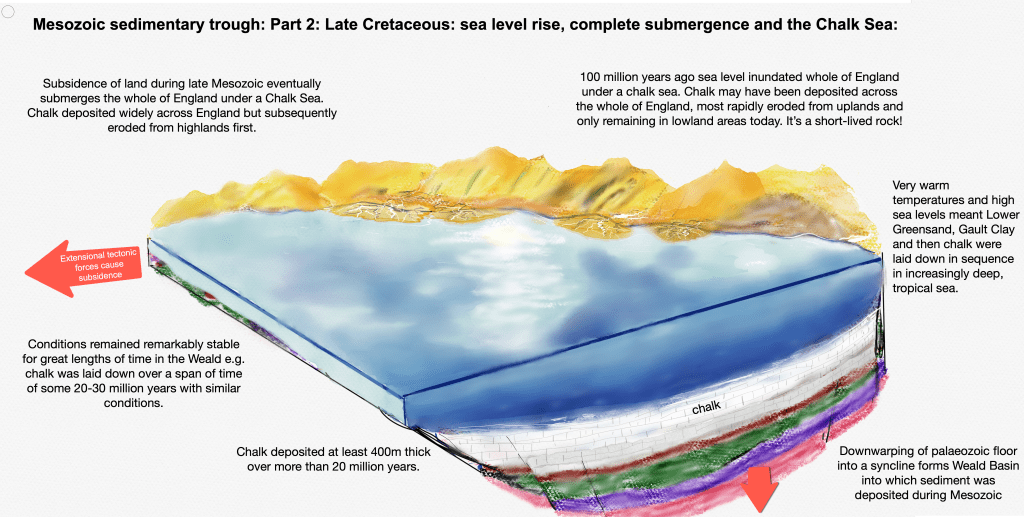

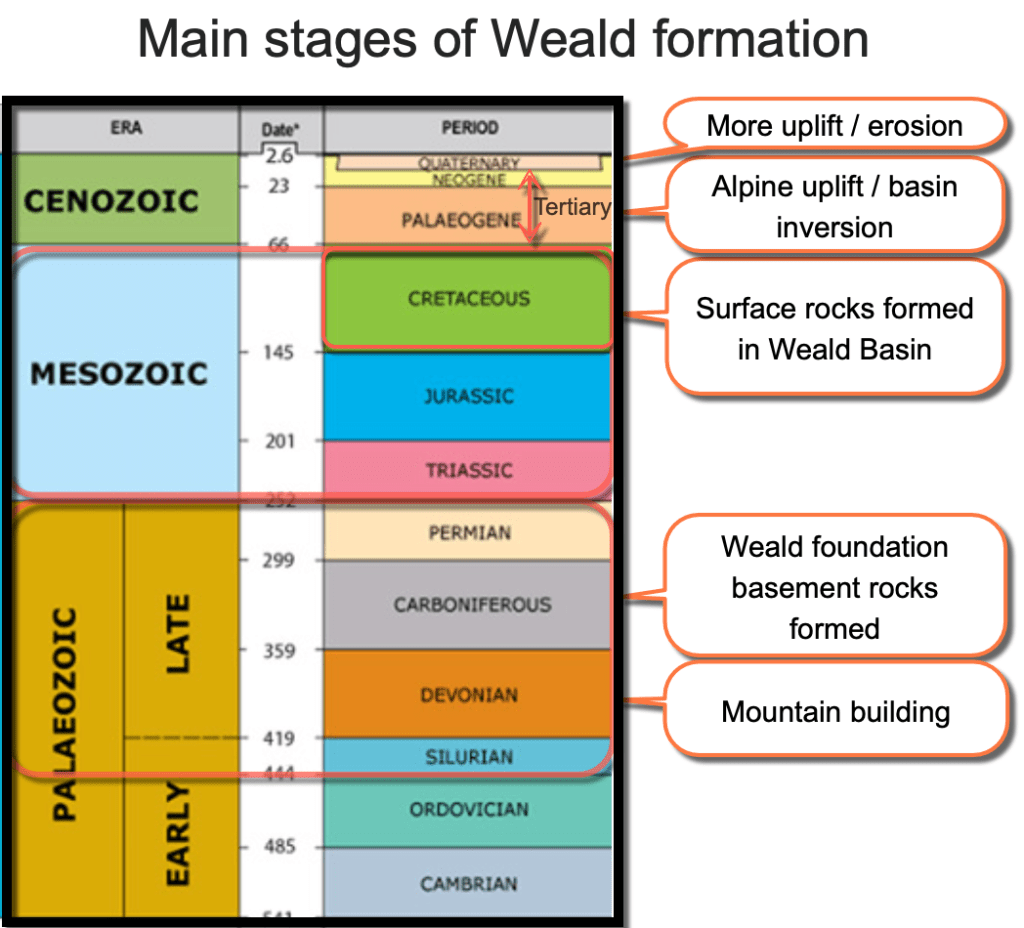

Part 2: The Mesozoic Trough: the 200 million year story of how the rocks beneath our feet were laid down in watery basins, mainly during the Cretaceous. The bands of sedimentary rocks around the Weald, from sandstones in the High Weald to Chalk on the Downs, were laid down during the Mesozoic. Changes in rock type mark the different environment where rocks were deposited..from muddy deltas where Iguanadon roamed, to deep tropical Chalk seas.

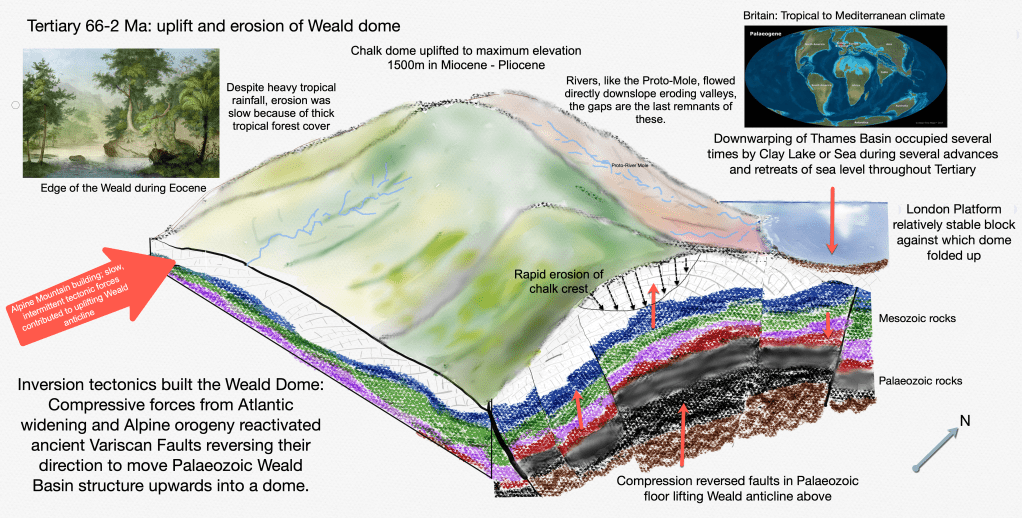

Part 3: Tertiary Uplift: the traditional story of Mid-Tertiary uplift of a huge dome and subsequent denudation has been revised by geologists as discoveries of the deepest Wealden structures have been made through borings and seismic surveys by, amongst others, the hydrocarbon and nuclear industry. However, exactly what happened in the Weald during the Tertiary is still a mystery and doesn’t seem to have been quite settled yet. Part 3 unravels the threads of that 65 million year history.

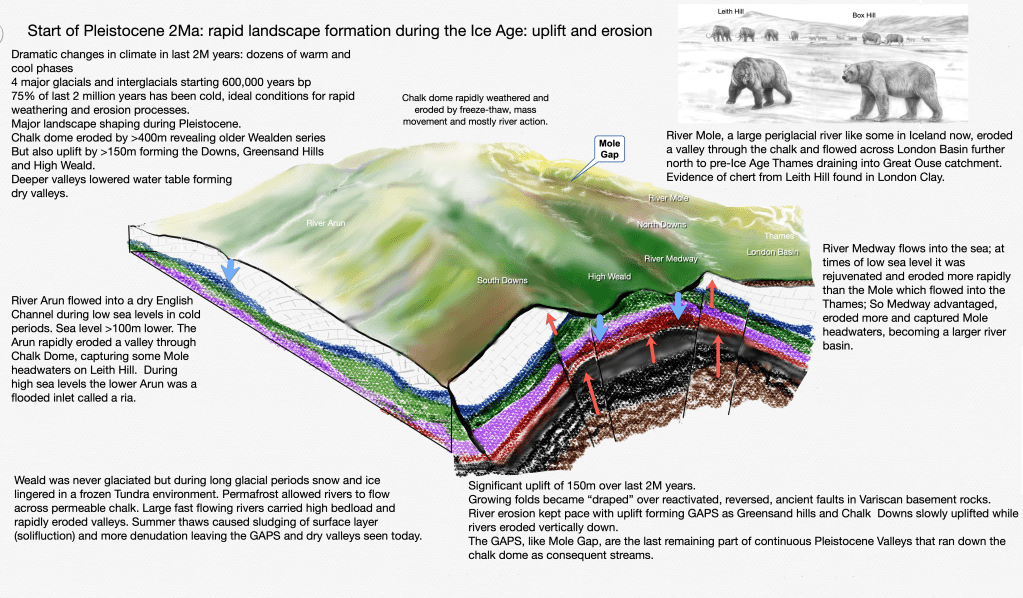

Part 4: Pleistocene Ice Age to now: The great fluctuations of climate in the last 2.6 million years have been responsible for rapid erosion and landscape change. For 80% of this time the Weald would have been a frozen, windswept Tundra. Brief periods of warmth caused permafrost to thaw, snow and ice to melt and torrential rivers to erode and transport debris into valleys. Warm interglacials and the spread of forests stalled landscape formation into a warm, sleepy state…which is where we are now.

During the last 400 million years our corner of the Earth’s crust has experienced extreme changes each responsible for adding or removing layers of the geological cake and sculpting the landscape into what we see today. By the way, the diagrams above are drawn by me and, when you see the large version in each post, you’ll see that I’m not an artist but hope they convey a part of the story well enough.

From tectonic uplift, subsidence under lakes and seas, windy arid deserts, lush tropical forests and, most recently, Arctic Tundra conditions during the Ice Age, each stage has brought different tectonic, erosion and weathering processes that have shaped the landscape. Sometimes the shaping of the landscape has been rapid, at other times the rate of change has been incredibly slow or even static. Let’s start by reviewing the current landscape through which the River Mole flows right now.

The Mole Landscape

The River Mole flows north into the River Thames, descending a modest 90m height over an 80km journey. It flows through a low relief landscape, meaning the difference between the highest and lowest elevations is relatively small, the highest point being 270m near Coldharbour on Leith Hill and the lowest point at the confluence with the Thames at Hampton Court at 9m. Hills in the catchment are a modest size and average slopes are a low gradient. The source starts at around 100m elevation just south of Rusper on the southern slope of a low ridge that extends across the Mole Valley to overlook Gatwick.

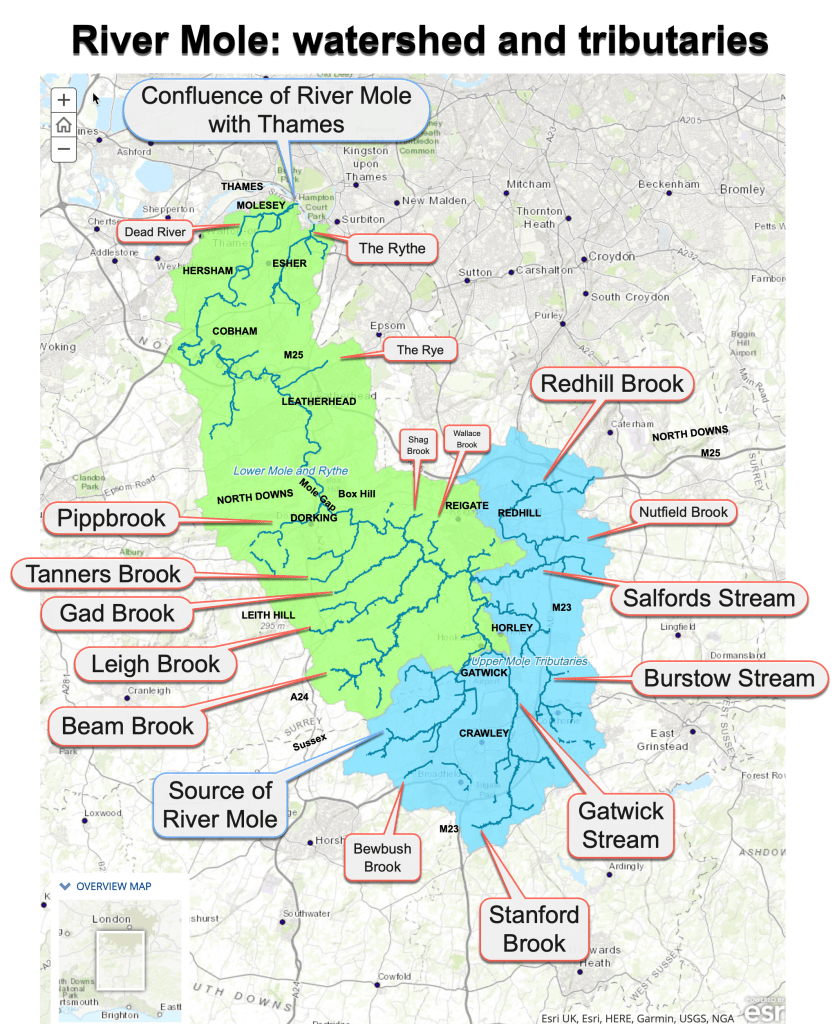

Numerous other tributaries spring from higher ground and more remote places on the watershed. Pippbrook rises from over 200m in a valley on the eastern shoulder of Leith Hill; Stanford Brook, which becomes Gatwick Stream, emerges from remote hills in Worth Forest south of Crawley, while Burstow Stream has tributaries rising from land in the far-flung south east of the catchment around Tulleys Farm near Crawley Down. There are no tributaries through the Mole Gap and only a few north of it including The Rye, rising from Ashtead Common, a bourne rising in Bookham which I think is called the Earbourne and the aptly named “Dead River” (a sluggish ditch) which flows into the Lower Mole just before the confluence with the River Thames at Hampton Court.

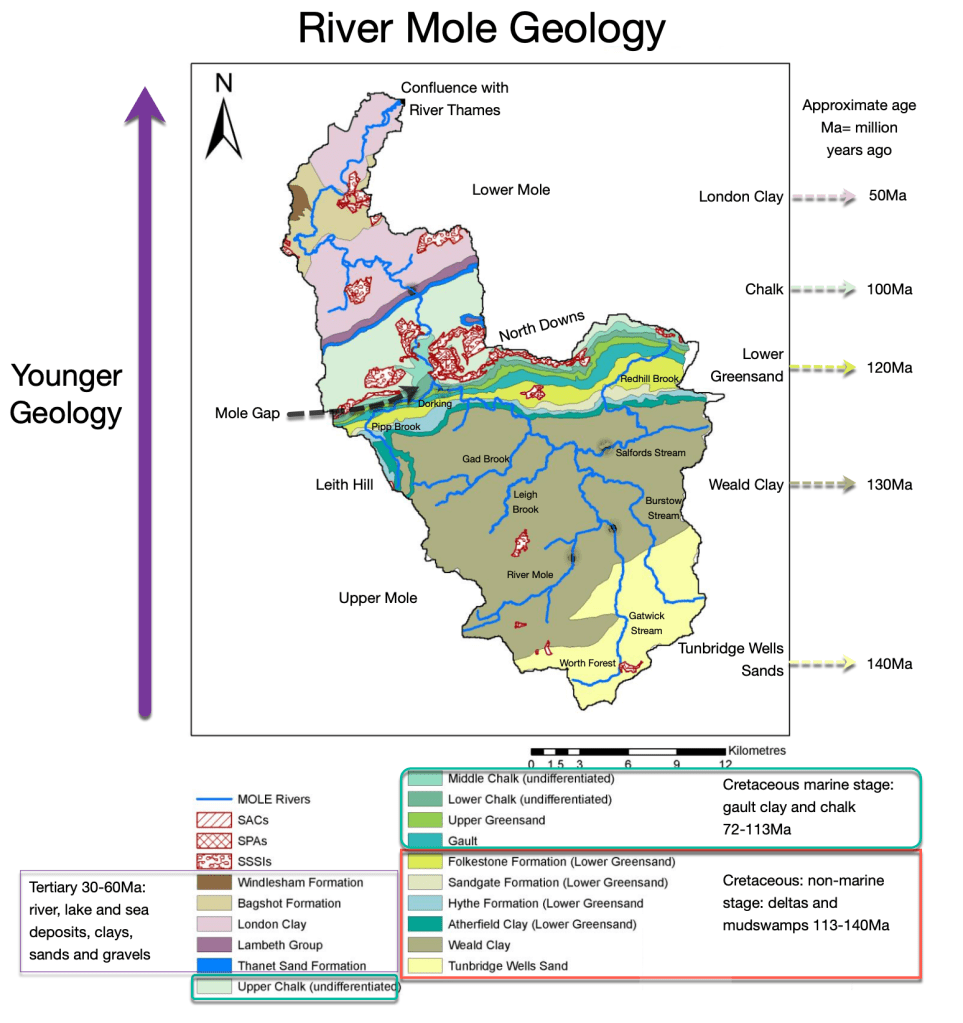

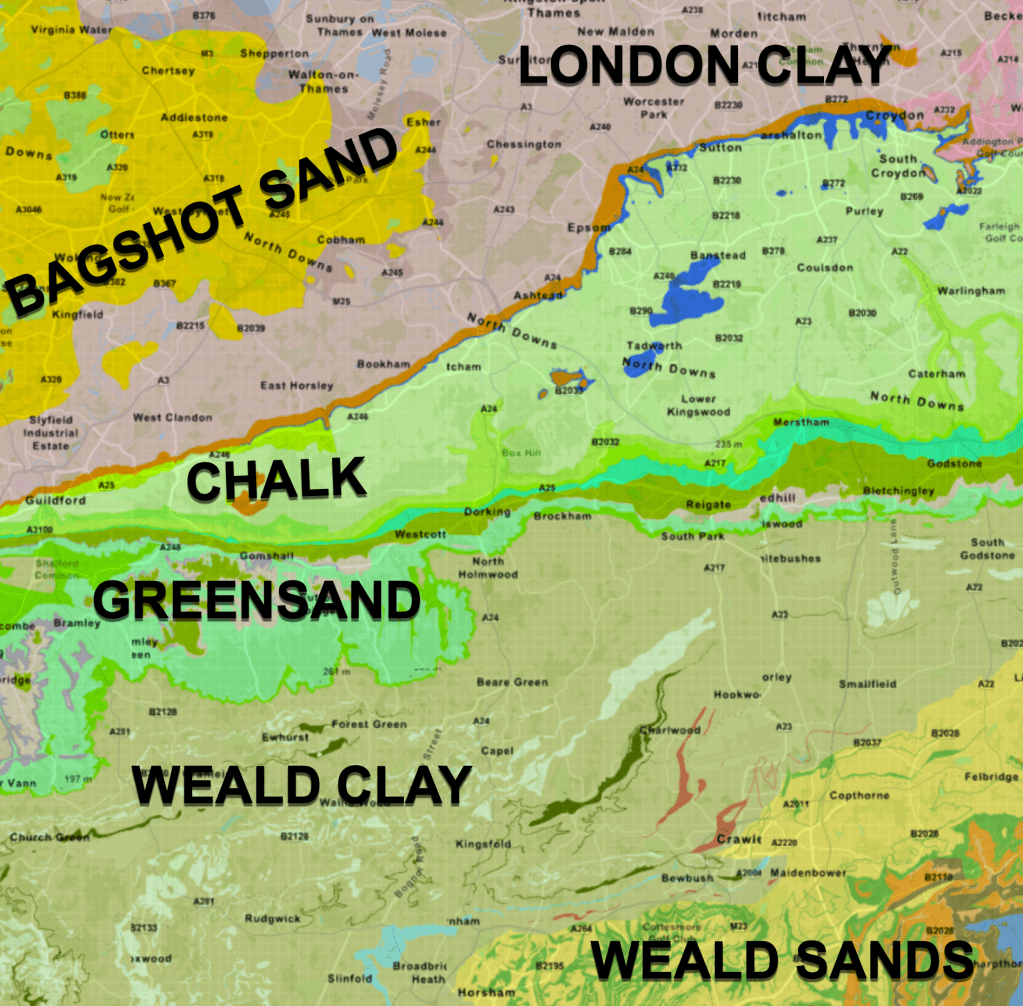

The surface rocks forming the majority of the Mole catchment formed quite recently between 50 and 140 million years ago (Ma). The rocks get younger the further north you go and they vary in how resistant they are to erosion.

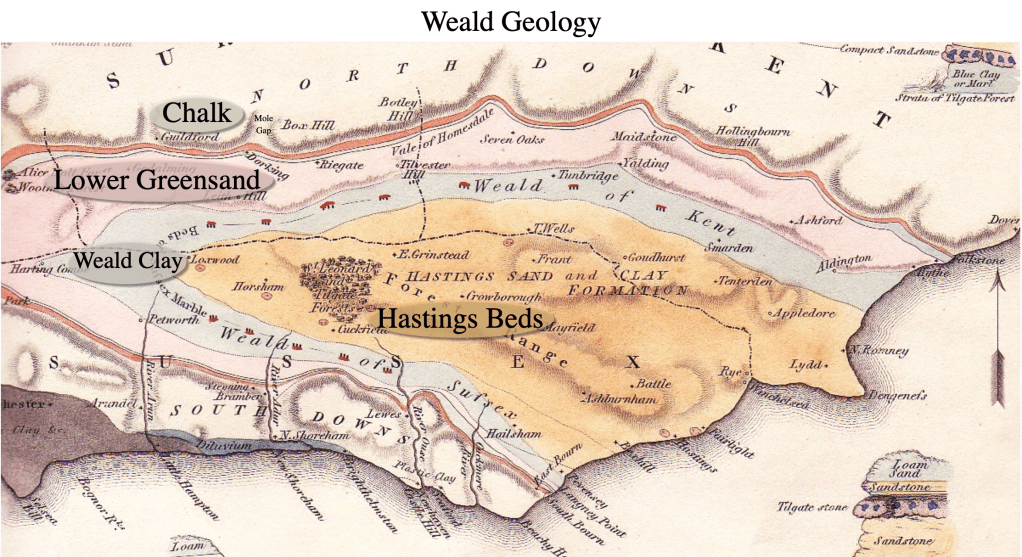

Using the rivers as a guide, the Gatwick and Burstow Streams rise from Tunbridge Wells Sands, part of the oldest geology in the Mole catchment. These rocks are relatively resistant sandstones and form the forested hills south of Crawley, easily seen from the M23 as you skirt the town. This range of hills forms the southern watershed of the Mole catchment and they continue east to eventually join up with the Ashdown Forest which forms the watershed between the Medway and the Ouse. Collectively, the rocks found in the central High Weald are known as Hastings Beds and were laid down in the Cretaceous around 140 million years ago.

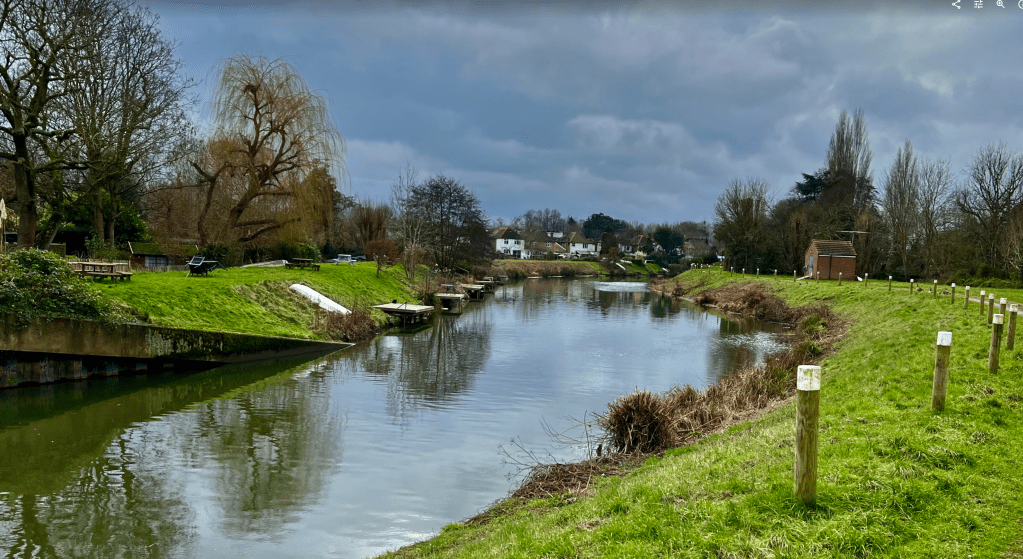

Beautiful streams in the Worth Forest (photo) form the Gatwick Stream that joins the River Mole north of the airport. Further tributaries also join the Mole north of Crawley where the river meanders across an extensive flat plain of impermeable Weald Clay all the way to Dorking.

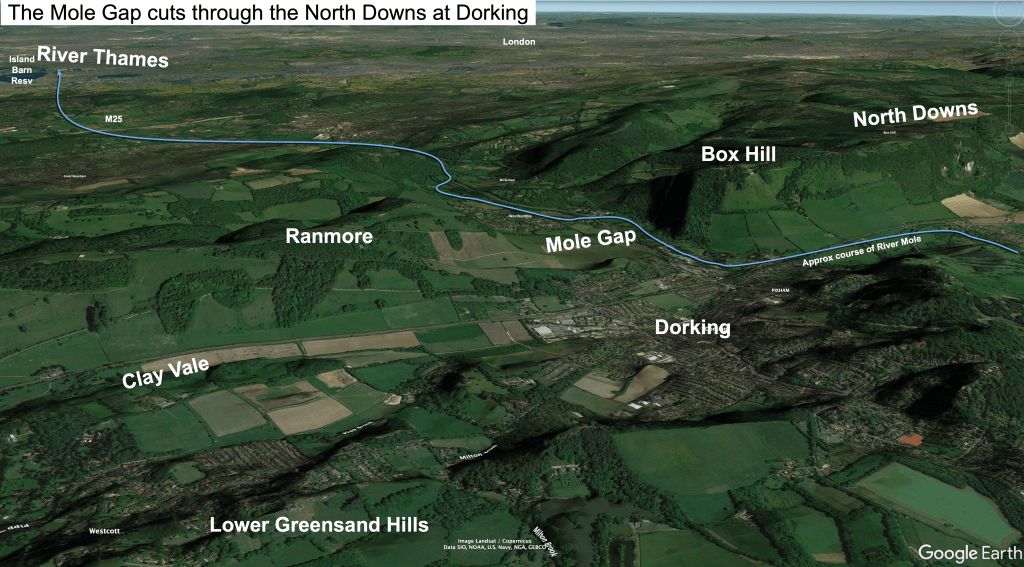

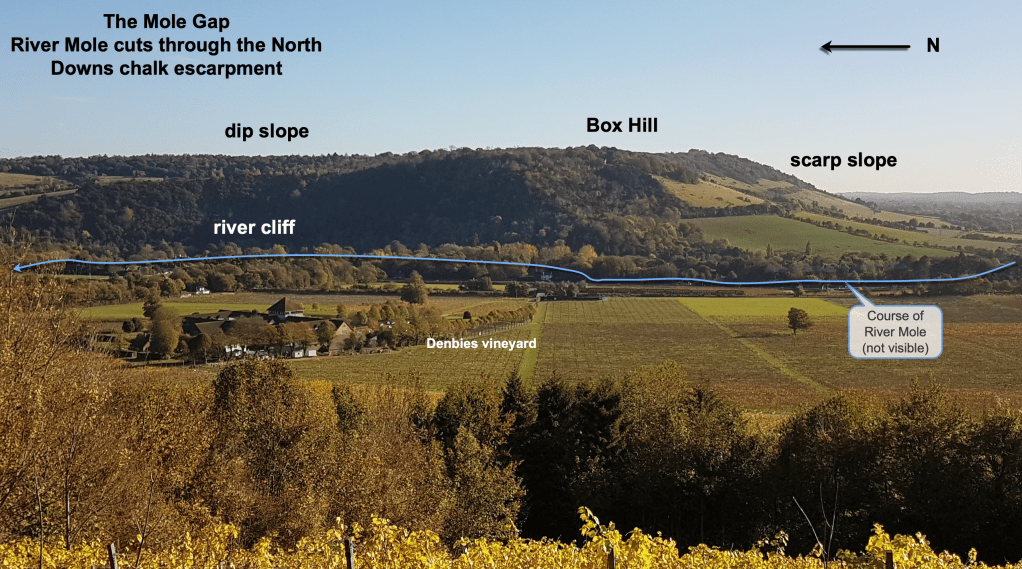

The Mole then flows north west to Dorking where it turns north to pass through the Chalk ridge of the North Downs between Box Hill and Ranmore via the impressive valley of the Mole Gap (photo). Chalk is permeable but is relatively resistant to erosion.

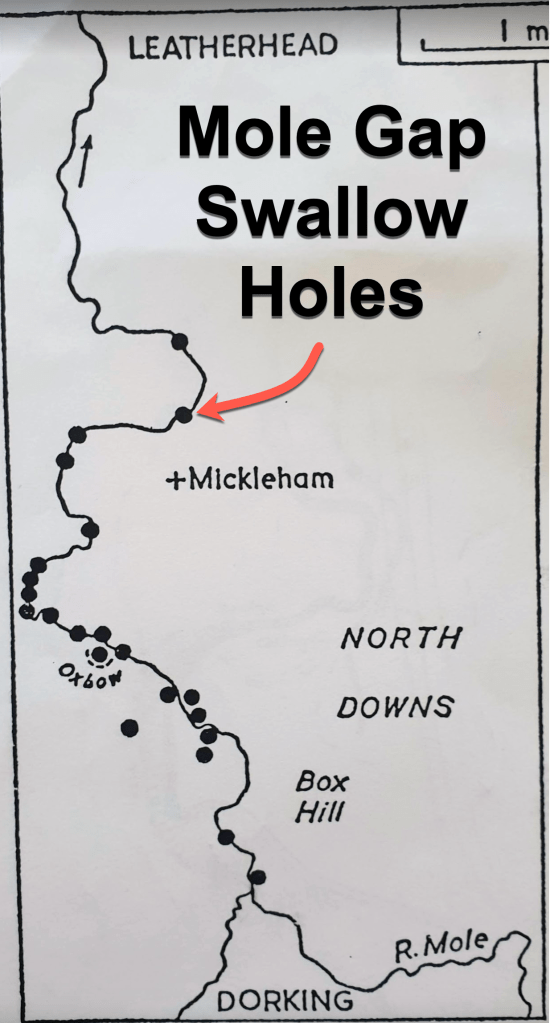

On the journey through the Mole Gap the River Mole famously passes over Chalk where some discharge is lost into the permeable rock through swallow holes. At times of very low flow due to prolonged dry weather, such as late Summer 2022, the River Mole can disappear underground into the chalk in the Mole Gap, reappearing at points of resurgence at Leatherhead, on located in Fetcham Pond, where the geology changes to impermeable clay.

After Leatherhead, the Mole turns north westerly across younger London Clay (50Ma) as it meanders three times under the M25. At Cobham the river meanders back to a northerly direction, passing over sandy Bagshot Formation.

At Esher the river enters a heavily managed course as it crosses back onto London Clay. It divides into two channels, the native Mole meandering north away from the straightened artificial Ember flood relief channel. The two water courses encircle Island Barn reservoir before joining again just before the Mole’s confluence with the River Thames at Cigarette Island Park with fine views of Hampton Court Palace on the opposite bank.

The bedrock geology found at the surface forms a simple pattern. The river flows mostly north or north-west across rocks that lie in more or less parallel bands going from oldest strata in the High Weald, 140Ma, to the youngest strata, around 50Ma, in London.

In addition to these bedrock strata, there are also “superficial deposits”, once called drift, which are patches of sands, clays and gravels deposited loosely on top of solid geology. This includes a liberal covering of Clay-With-Flints across the top of the Chalk Downs, a gravelly “beach” deposit found over 180m up on Netley Heath (just outside the catchment but worth mentioning) and widespread river deposited sediment in valleys known as terrace gravels and alluvium.

For the Weald as a whole, the rock outcrops appear in parallel and form concentric horseshoes around the central High Weald, again going from oldest to youngest on the edges.

While the geology is quite straightforward, the landscape and drainage pattern of the Weald and the Downs as a whole has been a challenge for geologists to explain and it remains challenging today with no unifying theory that convincingly explains everything.

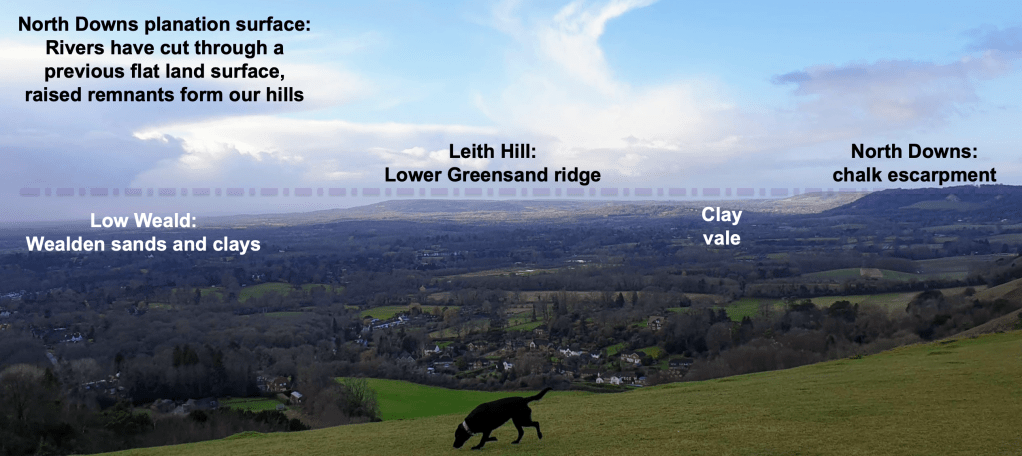

Follow any Wealden river downstream from a source and soon you will spot something odd. Most streams start from high ground around 200m in the sandstone hills of the High Weald, flowing away to form main channels across clay plains. However, not far downstream they meet lines of hills, or escarpments. Rivers flowing north meet the Greensand hills first, but all meet the Chalk Downs, a striking escarpment rising over 200m high in places.

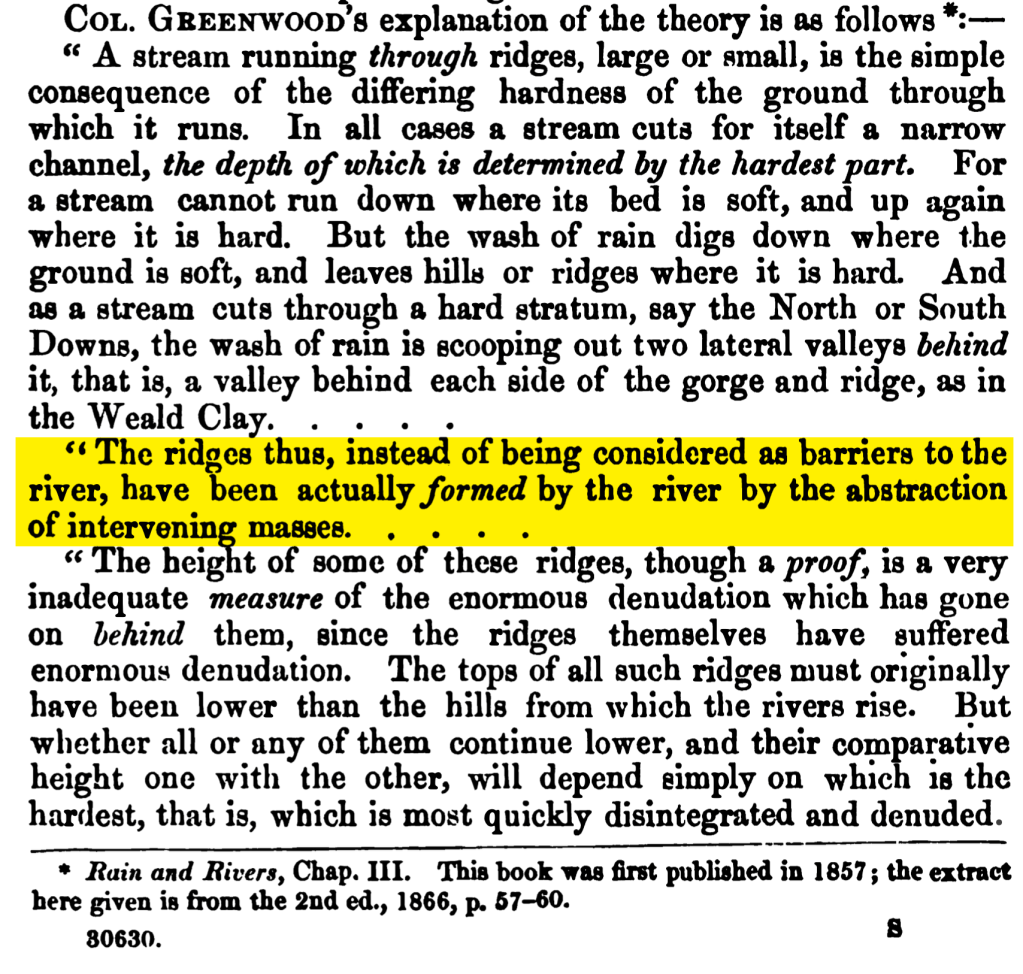

Strangely, these modest, under-sized rivers all manage to pass through convenient gaps in the Downs, flowing straight through the hills via outsized valleys that carve completely through the escarpments as if the hills were not there!

The Mole Gap is one such through-valley, there are at least eight other river gaps cutting through hills around the Weald, excluding numerous elevated dry “wind gaps” which no longer host a river.

Globally, plains with rivers cutting through lines of similar height hills of varied rock types are a common landscape. Geologists call these landscapes planation surfaces. The theory goes that the original surface was assumed to have been formed by time spent submerged under the sea with waves planing-off relief. Later uplift allowed rivers to cut through and denude the raised plain, leaving only isolated hill tops at similar height as evidence of the former layer.

Early Theories

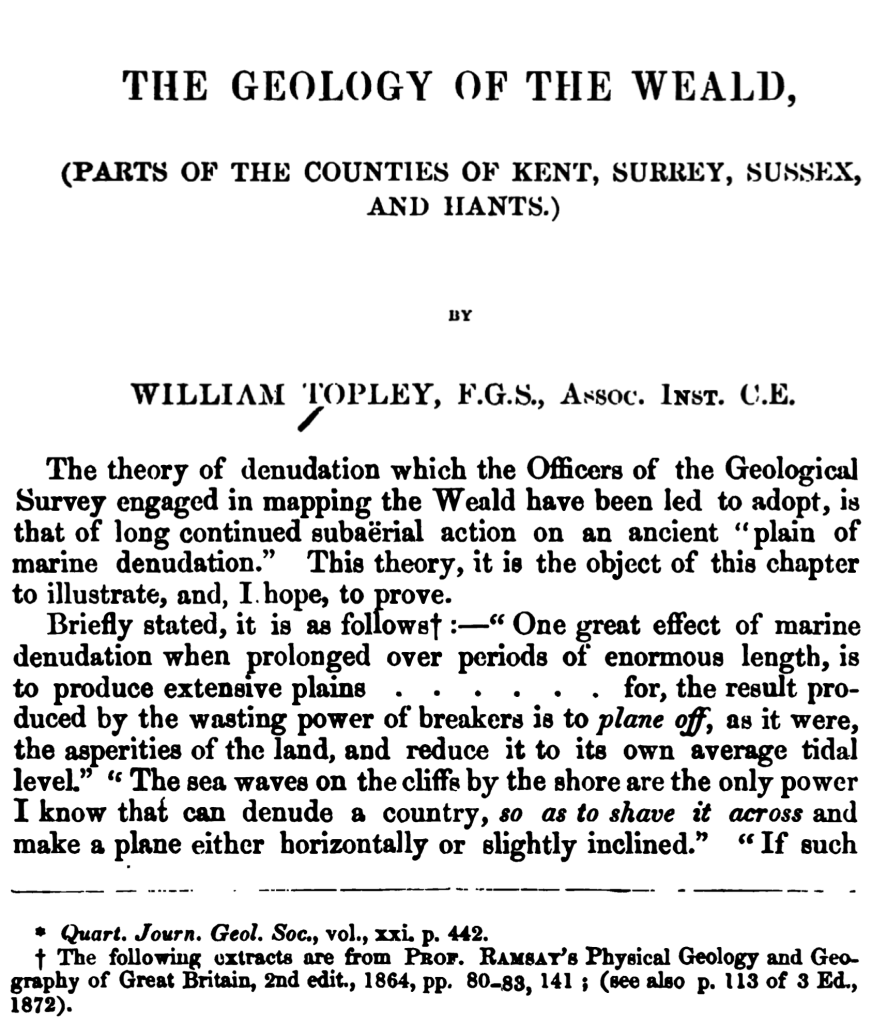

The marine-planation theory was a popular explanation of the Weald landscape in the 19th Century. It seemed to account for the apparent concordance of hill top height. The text below is from the 1874 account of “The Geology of the Weald” by W Topley. I have not come across anything that better describes the landscape from such a deep wealth of personal knowledge! The description of landscape formation is wonderful..

Here is another lovely explanation from the same book accounting for the apparent conundrum of rivers flowing through lines of more resistant hills via gaps like the Mole Gap.

So, next time you get a view from the Downs or Greensand ridge notice how the distant hills seem planed-off to a similar height of 200m around which rivers like the Mole have eroded large vales between the hills and cut impressive gaps directly through them. Marine planation might explain some of this landscape but modern geology has found evidence to suggest this is by no means the entire story.

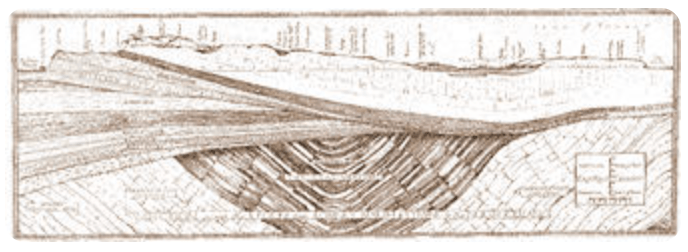

I love the idea that Nineteenth Century geologists were fascinated by the modest landscape of the Weald. Indeed, it occupied the life work of some famous practitioners such as Robert Godwin-Austen.

Explaining the Weald has fascinated geologists for centuries but still remains a challenge as mentioned here by one of the foremost geologists writing about the Weald in recent times.. D.K.C.Jones,

“The Weald must rank as one of the best-known denuded dome landscapes in the world, and yet great uncertainty still exists as to

Jones, D.K.C. (editor), 1980. The Shaping of Southern England, Institute of British Geographers Special publication, No.

its geomorphological evolution.”

A few early ideas explaining the formation of the gaps and the Weald can be ruled out straight away.

Glaciers are effective at eroding clean through hills by deepening and widening valleys but, whilst cold glacial periods were important in shaping our local landscape, ice sheets never got this far south in England. The maximum extent of ice sheets reached just north of London in one of the first and most extreme cold periods, the Anglian Glaciation, around 450,000 years ago. The Weald would have been under extremely cold peri-glacial Tundra conditions for 85% of the last 2 million years. Associated weathering and erosion and transport processes involving deep snow and freeze-thaw action of ice has certainly played a part in the formation of the Weald but full glacial conditions on the Downs must be discounted.

Despite not being glacial, the climate over the vast majority of the last 2 million years has been cold! Think of a place like Southern Iceland now, away from the glaciers, where large rivers carry huge volumes of meltwater and bedload in braided channels, and treeless slopes suffer regular freezing and thawing in extreme conditions. Summers are brief and cool while winters are brutally cold. This would be a climate similar to the Weald for most of the last 1 million years at least: a place of rapid landscape change on the edge of ice sheets.

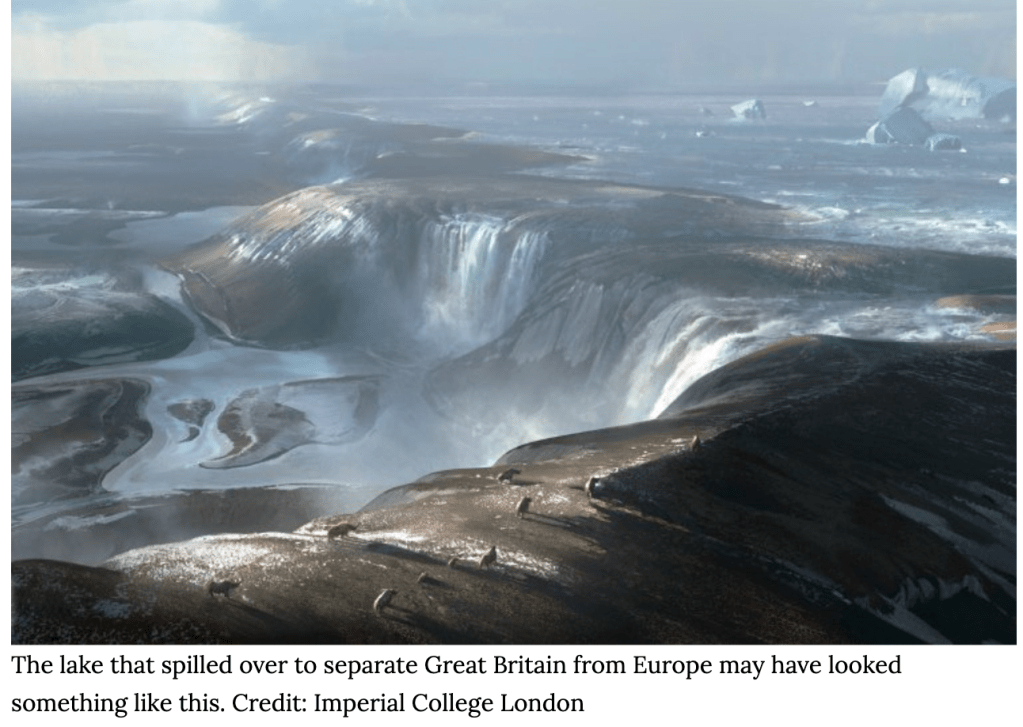

Theories involving catastrophic floods and overflow channels have also been suggested. Not far from the Mole, the River Thames flows through the Chalk ridge of the Chilterns via the Goring Gap. The accepted theory for this gap involves a large pro-glacial lake that filled up across Oxfordshire, dammed by ice sheets further north and the Chilterns in the south. The lake brimmed full as ice melted and eventually found a low point in the Chiltern hills to overflow into the Thames Basin. The torrential overflow, constricted in a narrow channel, rapidly eroded the Goring Gap. Whilst tantalisingly similar in shape, geologists have found no evidence of catastrophic lake overflows forming the Wealden gaps. So, as tempting as it seems being so nearby, the “Goring Gap” theory must be ruled out. Similarly, the story of the English Channel involves catastrophic breaching of the land barrier formed by a continuation of the North Downs chalk ridge that once linked England to France.

The Chalk barrier, the Weald-Artois Ridge, was breached across the Dover Straights when ice sheets in the North Sea dammed a massive meltwater lake which then overflowed in a mega-flood during the Anglian Glaciation, 450,000 years ago. This torrential overflow rapidly lowered the Chalk ridge to form the English Channel which became a large river system draining the Rhine and Thames south west into the Atlantic until sea levels rose to drown the entire valley and form the Channel during warm interglacials. Evidence for the overflow exists under the Channel in the form of giant plunge pools and gorges eroded by the torrential overflows. Sadly, despite being nearby, no evidence for a mega-flood exists in the Mole Gap.

Early theories also considered the Chalk inward-facing escarpments to be abandoned sea cliffs (Lyell 1833). Whilst it’s true the Weald has been submerged numerous times, the scarp slopes and chalk gaps of the North and South Downs have not been eroded by the sea.

Without glaciers or the sea or overflow channels, the gaps in the Downs can only be explained by looking back to a time when the Wealden rivers drained a landscape that was completely different from what we see today. Geologists have discovered an incredible story that reveals the origin of the gaps in the Downs. It turns out the Mole Gap, and gaps like it, is the last remnant of impressive valleys carved by torrential rivers that cascaded from higher hills in the centre of the Weald.

Having outlined the landscape and early attempts to unveil the mystery, let’s dig back to the beginning to begin to understand the formation of the River Mole and the wider Weald. This means going back 400 million years, so buckle up, it’s a big story!

Palaeozoic foundations

We can think of the formation of a landscape something like building a house. The foundations are first to go in. For the Weald this would be the oldest rock foundations laid down between 300 and 400 million years ago in the Palaeozoic. These rocks would become what geologists call the “basement” or Palaeozoic Floor. They are now buried under several kilometres of more recent, younger, overlying rocks. Kent coal, for example, is found up to 3000 feet or 915m below the surface.

A cross-section of east Kent from Lympne on the English Channel to Margate on the North Sea.

Basement rocks include a variety of rock types reflecting the climate that prevailed when they were laid down, whether the land was above or below sea level and how much erosion was going on to form sediments. Whilst volcanoes were at times not far away, none of the rocks in the Weald have a volcanic origin. Wealden rocks are all sedimentary. This means they are the product of eroded debris or dead carbonate rich life forms accumulating in quiet conditions, like an estuary, a delta, lake or sea, and being compressed and cemented into solid rocks.

The whole Palaeozoic era spanned an unimaginable 300 million years. From the Weald point of view, we are “only” really interested in a time from mid-way through when our deepest and oldest basement rocks were being deposited. Little is known about the detailed structure of the oldest Palaeozoic rocks which form the basement floor of the Weald because they are buried several kilometres beneath the present day surface.

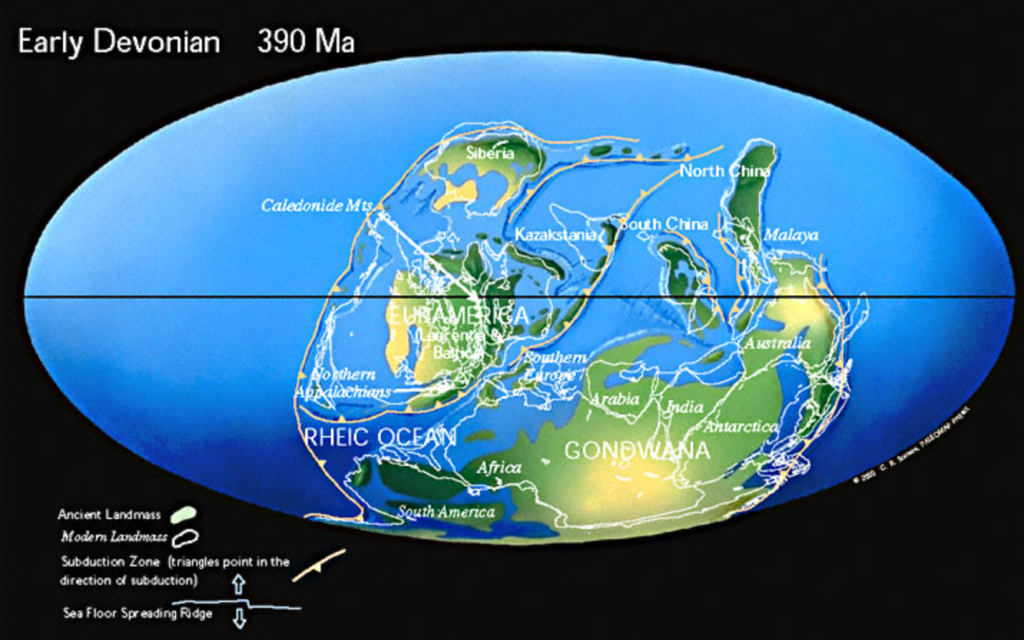

The Palaeozoic was a time of continental upheaval with blocks of land being thrust up into mountains and then eroded away, with eroded debris washed by rivers into subsiding basins. Some of the oldest Wealden rocks are marine deposits laid down in shallow seas which filled up with silt and mudstones during the Silurian period, 430 million years ago. All of these oldest rocks are heavily folded and faulted due to the earth movements that took place in this mountain building phase of Earth’s history. At this time most land, including our bit of the crust, lay south of the Equator and animals were evolving legs to move onto dry land in search of the first plants.

During the Devonian, the arid desert climate and erosion of the huge Caledonian Mountain chain, favoured the deposition of sandstone in the Weald, now buried 3km beneath the surface. There were still the mountains of the Anglo-Brabant Massif to the north and an ocean further to the south.

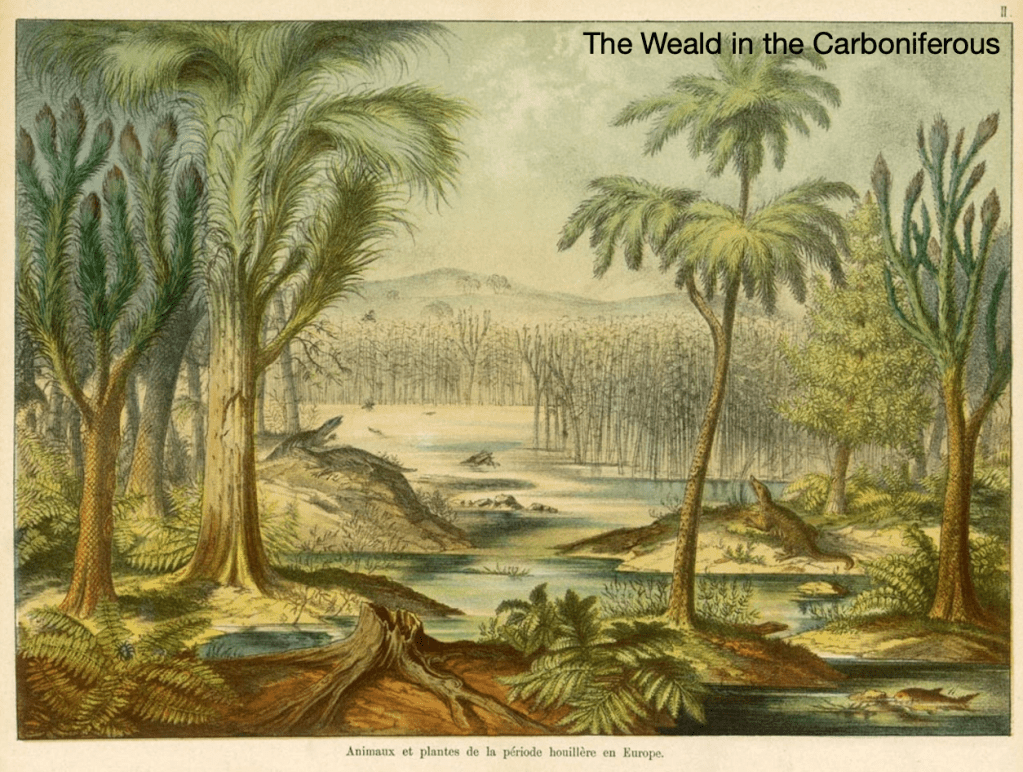

The Carboniferous, 299-359 million years ago, was a crucial time for the nascent Weald. Britain moved Equator-ward and the climate became increasingly hot and wet with the growth of swampy tropical forests. Higher temperatures caused sea levels to rise and forest swamps were slowly drowned. The drowning trees died, were buried and decayed in anaerobic conditions under more sediment and compressed into coal seams now found below Kent. The Carboniferous period saw the greatest sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere into the ground in Earth geological history. It took more than 10 million years to capture the carbon but humans have emitted much of it back into the atmosphere in less than 100 years!

“The major structural framework of southern England

Lefort & Max 1992

was formed during the Variscan Orogeny around 300

Ma, when the Armorican crustal block of Brittany

pushed northwards towards the Midland Craton of

central England”

A key feature of the Palaeozoic was mountain building, periods known as orogenies. Plates were colliding and assembling the supercontinent of Pangea. Britain found itself in the middle of this continental collision, on the flanks of a mountain chain called the Variscan Mountains which formed towards the end of the Carboniferous. This range ran along the edge of a continent that included North America. The Appalachians are an ancient eroded remnant of the Variscan range surviving today. While there were volcanoes and intrusions of magma in what would become South West England, the Carboniferous rocks below Surrey are limestones and shales.

The “Variscan Front” shown on the map above, is the northward limit of the main Variscan Mountain fold belt. It runs about 1km deep through Addington.

In our area, the result of plate collisions caused major faults or cracks to form in the basement rocks. Importantly, and by chance, these faults ran east-west across the basement rocks that would eventually be important in the formation of the Weald Basin during the Tertiary uplift.

Towards the end of the Carboniferous, 300 million years ago, the Weald became a dense Equatorial forest in a subsiding watery basin sinking between major faults, surrounded by stable landmasses, particularly to the north. Through the following arid Permian period, tectonic pressures caused more subsidence of the Weald into a downwarped basin structure known as a syncline.

At this point, the Weald Basin was all set to spend most of the next 200 million years at various states of submergence under water. From just dipping it’s toes into deltas and lagoons near the shore of lakes to complete submergence under the sea, the Weald Basin would become the final destination for sediment eroded from the collapsing mountain chains around it. The geological structure of the Weald Basin created in the Palaeozoic would become crucial to the deposition of sedimentary rocks that went on to build the Weald we see today.

Thank you for reading my post! Part 2 covers the Mesozoic.

References:

History of the major rivers of southern Britain during the Tertiary Compiled by Philip Gibbard & John Lewin https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/tertiaryrivers/

D K C Jones London School of Economics: The Weald p73-101 A. Goudie and P. Migoń (eds.), Landscapes and Landforms of England and Wales, World Geomorphological Landscapes,

Nick Baker 2016: The Problem of Post-Cretaceous Drift Deposits https://mfms.org.uk/pages/pdf/Muck%20notes.pdf

Pliocene beach under London https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2018/03/19/workers-discover-ancient-coastline-in-west-london/

Hansen, D.L., Blundell, D.J. & Nielsen, S.B. 2002–12–02. A Model for the evolution of the Weald Basin. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, Vol. 49, pp. 109–118. Copenhagen.

South East Research Framework Resource Assessment and Research Agenda for Geology and Environmental Background (2018 with additions in 2019)Geological and Environmental Background Martin Bates and Jane Corcoran

Migoń, P. & Goudie A., Pre-Quaternary geomorphological history and geoheritage of Britain. Quaestiones Geographicae 31(1), Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań 2012 https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.2478/v10117-012-0004-x

British Geological Survey: Geology Viewer and Lexicon https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/?_ga=2.7037298.1327190817.1675929737-1868444071.1675929737

Mole Valley Geology Society https://www.mvgs.org.uk/geomorphology

How Britain Became and Island: Lecture with Professor Phil Gibbard. https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/englishchannelformation/

Variscan Orogeny https://variscancoast.co.uk/variscan-orogeny

The Geology of the Weald. William Topley FGS. Published HMSO 1874

Relative Land-Sea-Level Changes in Southeastern England during the Pleistocene, Vol. 272, No. 1221, A Discussion on Problems Associated with the Subsidence of Southeastern England (May 4, 1972), pp. 87-98 (12 pages) R. G. West Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences

Leave a reply to Making Mole Hills out of Mountains: Part 3 – The Mole Story Cancel reply