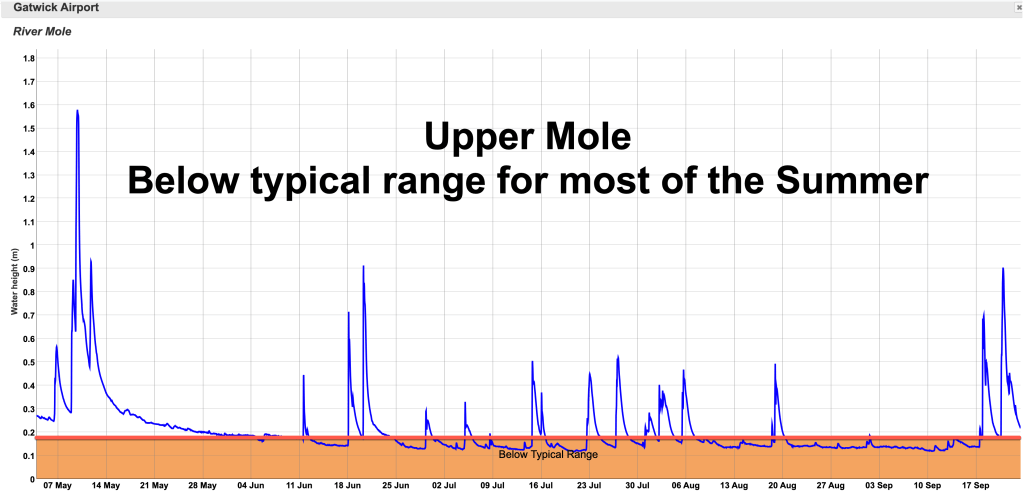

Here is a quick review of two recent early Autumn rainfall-runoff events producing quite contrasting responses in the River Mole. Just to point out this was not a flooding event, far from it…the river has been in unusually low flow for much of the Summer and this early Autumn rain was most welcome to top up river levels to nearer where they should be.

This is part of an on-going study to understand how our local river reacts to rainfall of different intensities, duration and distribution. It’s a work in progress so any discussion and observations are welcome in the comments below.

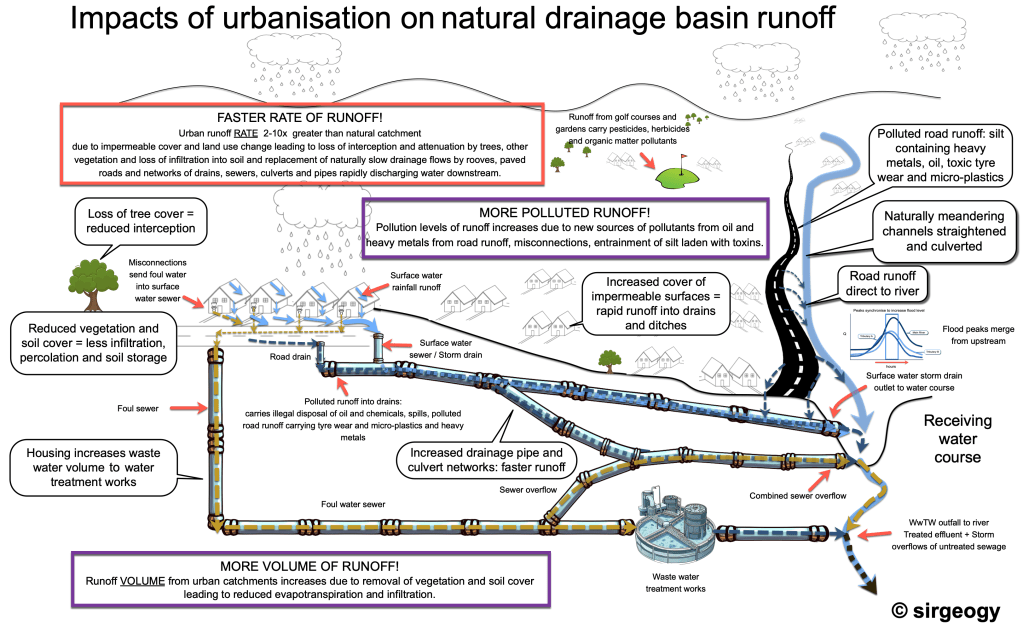

How our river reacts to rain, or the lack of it, is important because flow is intimately linked to water quality and river health. Examples of flow connecting to river health include storm overflow discharges, accelerated bank erosion carrying high silt load into the river, the effects of road and surface runoff flushing pollutants into water courses. The impacts of unmanaged urban and agricultural runoff all create an enhanced pollution hazard for the river.

Nature Based Solutions including Natural Flood Management can moderate flow and improve river health by simply tackling how water runoff enters the river even where directly reducing, for example storm overflows, is problematic and slow. Ultimately, the route runoff takes to enter the river determines how polluted it is.

Anyhow, let’s now look at these two Mid-September rain events and see what clues they provide to rainfall-runoff processes in the Mole.

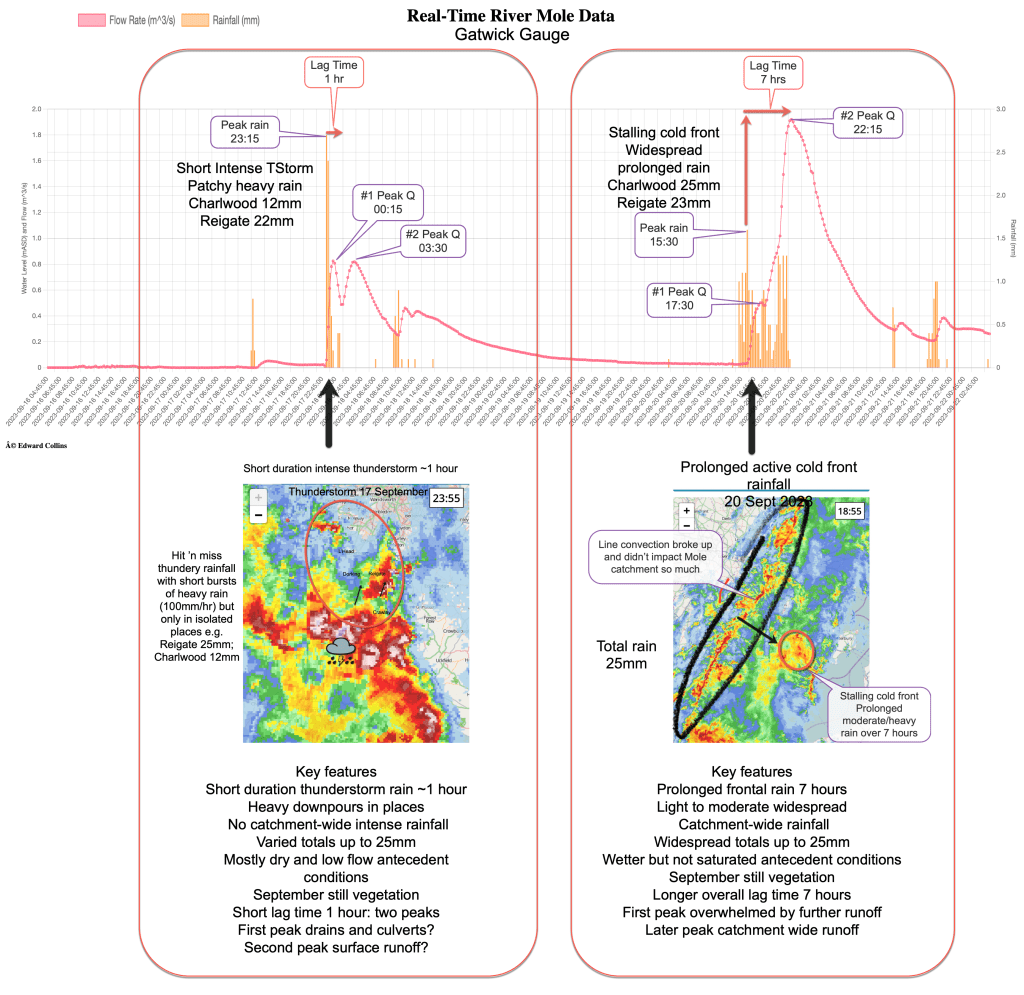

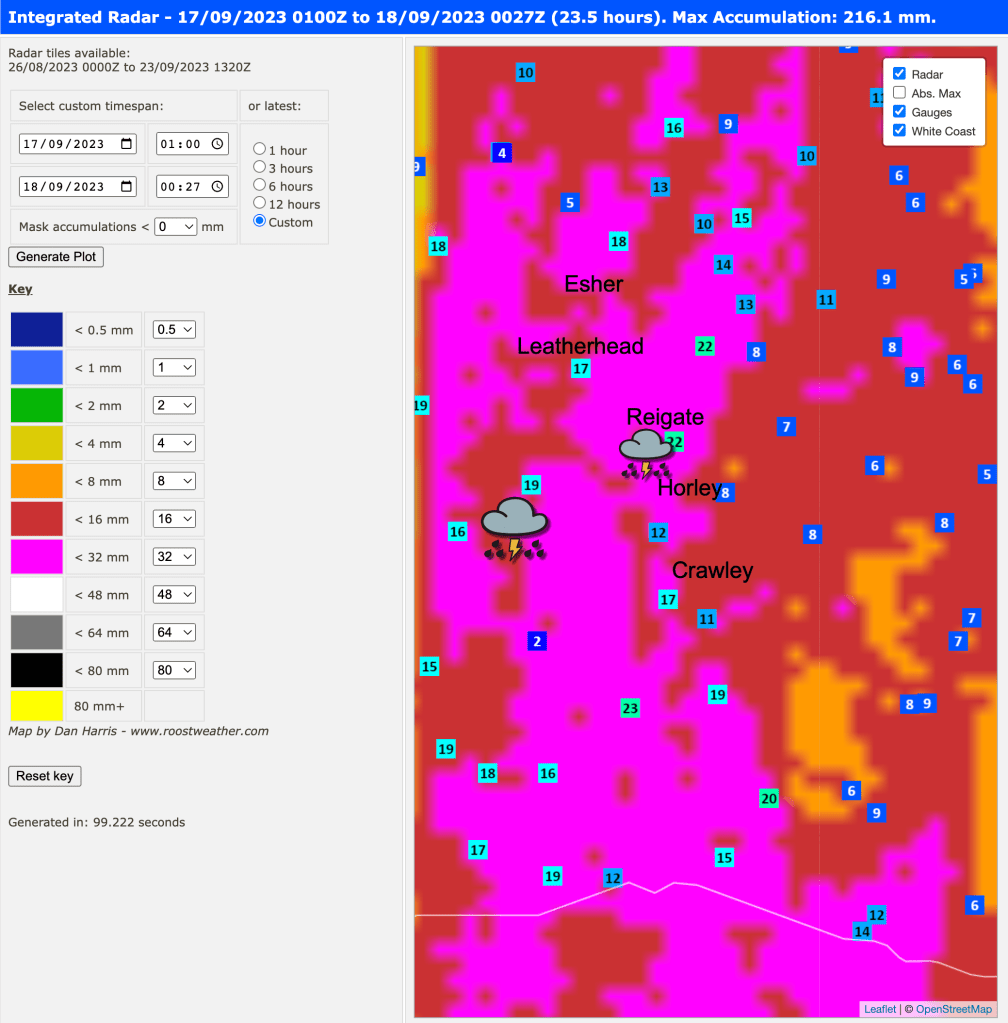

The first rainfall was a plume event bringing lively thunderstorms tracking north from the Channel and popping up some heavy rainfall as they passed over the Mole catchment. The thunderstorms dropped intense rainfall in places but only for a short duration. In such places rain accumulated up to 25mm in just 45 minutes. In other places much less rain fell. For example, while Reigate had 25mm of rain over 45 minutes, Charlwood only recorded 12mm and Burstow a paltry 7.8mm during this event. The distribution of rain accumulation shown below is from radar and local gauges.

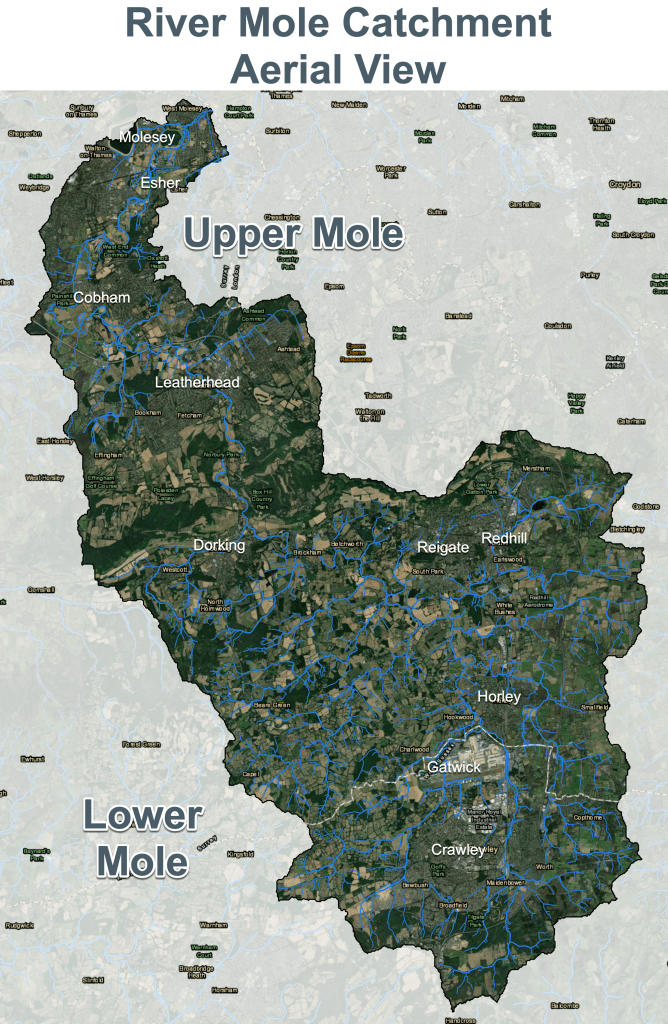

This highlights the patchy nature of thunderstorm rain.. it is rarely catchment wide and the nature of the land where the intense rain falls, whether it’s urban or rural, fields or woodland, makes a tremendous difference to the response of the river. In this case, the heaviest rain did not seem to impact Crawley so much but popped up further north and west towards Reigate and across the North Downs, a more permeable catchment, less urban and with streams contributing far less to overall river discharge. Indeed much of the heaviest rain probably fell across the chalk Downs where drainage density is very low.

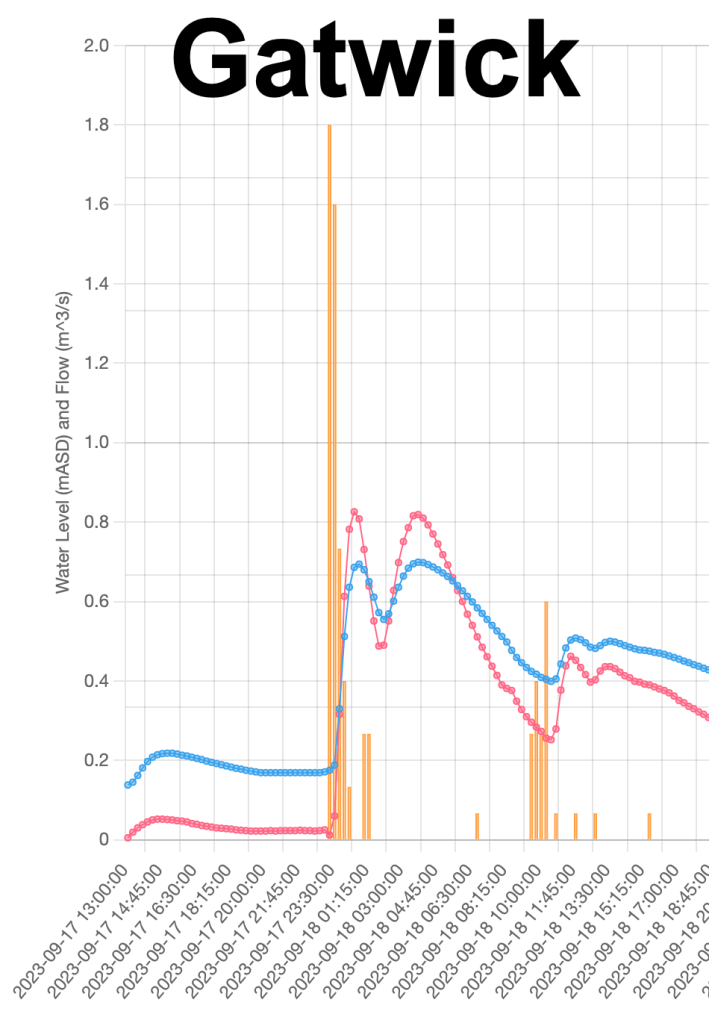

The River Mole at Gatwick responded very quickly to the thundery rain with two minor peaks of discharge, the first in less than an hour of peak rain intensity. The peak discharge was a modest 0.8m3/s. I interpret these very rapid initial peaks as local runoff from roads and urban areas. Unfortunately, identifying the exact provenance of these flows will need much more investigation. The Gatwick Gauge is upstream of the airport so the two early peaks do not represent any runoff from the runways, which is attenuated to grassy runoff rates anyway.

There is a third, lower, peak which follows another shower in the morning of the 18 Sept. Again this shows the characteristic rapid river response within an hour or so. This has been an unexpected feature of summer rainfall in the Upper Mole.. the lag times have been very short indeed. This is contrary to what we expect as traditional explanations suggest summer lag times are longer because of enhanced interception and evaporation and transpiration by vegetation in leaf. The findings this summer have shown lag times are shorter. This might be due to local drains and culverts collecting the short bursts of summer rain and conveying it quickly into water courses, while the drier warmer and more leafy conditions across the wider catchment mean more distant flows simply never make it to the river but are instead intercepted and lost through evaporation, transpiration or soil storage. The result is that only the first “portion” of the rising limb in summer rainfall ever reaches the river. That’s just a theory for now and needs more investigation of course but goes some way to possibly explaining the very short lag times in Summer in the Upper Mole catchment.

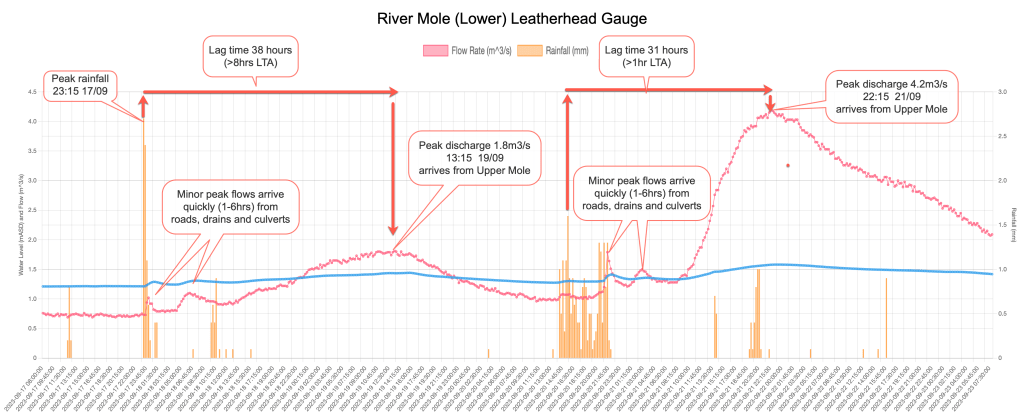

Interestingly, the short lag times in Summer only apply to streams in the Upper Catchment . In particular, the Gatwick and Horley gauges recorded rapid responses some 4 hours quicker than the long term average lag time in those locations. Further downstream in the main channel at Dorking and into the Lower Mole at Leatherhead and Esher the lag times are longer and response somewhat slower than the average, for example up to 8 hours slower at Leatherhead than the long term average lag time. This is in line with expectations as, overall, summer rainfall is slower to reach gauging stations from the more leafy surroundings as more of it is intercepted. Nevertheless, even in the Lower Mole there is evidence of these fast minor peak flows arriving earlier than the main peak discharge as shown below.

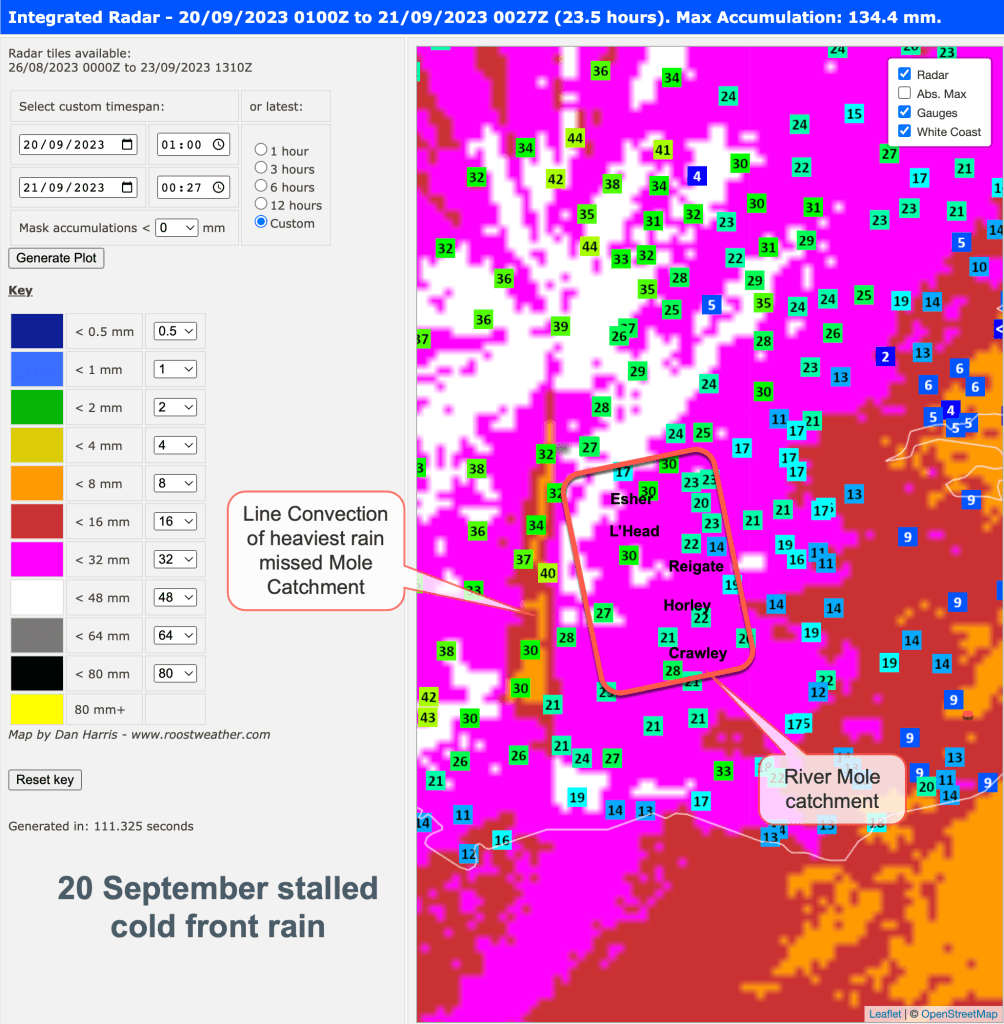

The second rainfall event occurred on 20 September and was brought in from the NW by an active cold front. The cold front developed a line convection feature which dropped very heavy rain but this broke up before it got to the Mole catchment so most rainfall for our area did not exceed 20-30mm for the 7 hours of rainfall duration.

This was the remnants of Hurricane Lee and the front progressed SE during the day and slowed and stalled dropping over 25mm of rain quite widely across the Mole catchment. This was a frontal rainfall event so had more widespread rainfall. It also had a line of heavy rain associated with convection but this never arrived in earnest as but broke up and didn’t impact the Mole catchment. So frontal rain dominated for 7 hours without the dramatically heavy rain associated with the line convection elsewhere to the north and west.

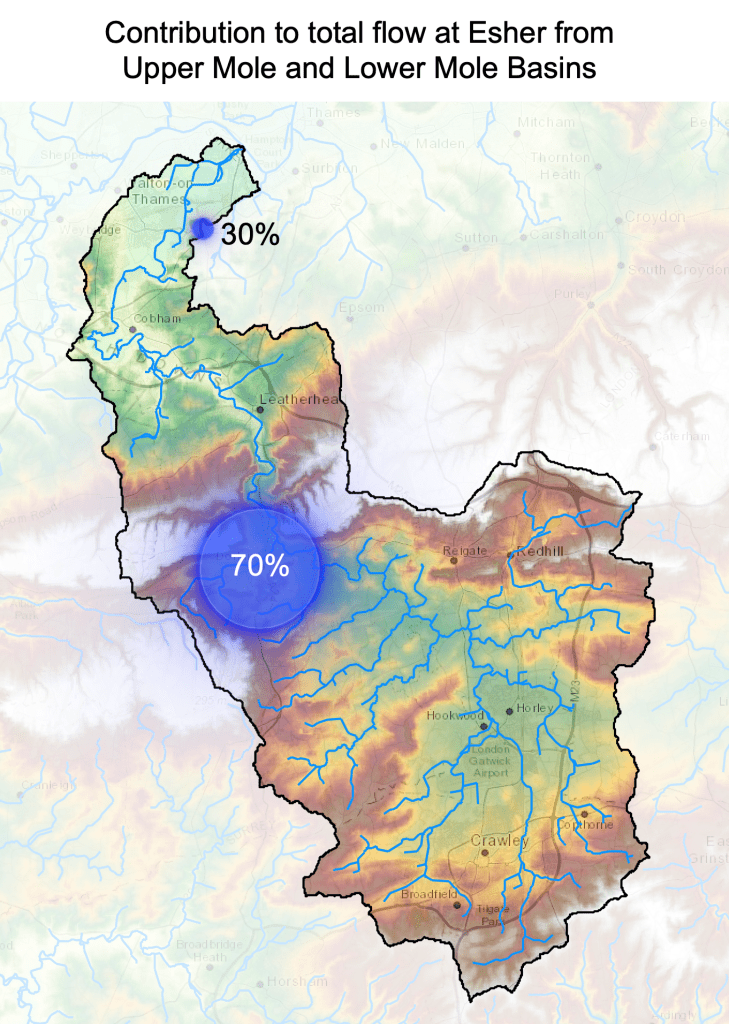

The response at Leatherhead and downstream still shows minor peaks in discharge arriving promptly into the river from local runoff, between 1 to 6 hours after the heaviest rain. There is then a long gap before the peak discharge from the Upper Mole arrives some 30 hours later. This response supports the contention that the vast bulk of river flow in the Lower Mole is provided by runoff from the Upper Mole, with only minor contributions from a few tributaries such as The Rye or Bookham Brook (dry for most of the Summer) or groundwater from the chalk aquifer which is low at this time of year.

The prolonged frontal rainfall event on 20 September across more of the catchment caused higher discharge but with a longer lag time. Interestingly, the lag time for this event was longer and slower at Gatwick than the long term average for the Mole. There is, however, still the hint of two peaks, as shown in the hydrographs above. This would support the theory that rainfall arrives very quickly from local drains, including field drains, and culverts but, on this occasion with much more prolonged rain, this initial peak was then rapidly overwhelmed by incoming surface runoff from the wider catchment. As Autumn progresses one can presume that this early local peak will be subsumed and undetectable as the ground saturates and vegetation dies back so that the wider catchment becomes the main contributor to river flow rather than just local urbanised runoff.

These observations regarding rainfall-runoff might seem rather niche but have importance when thinking about how to tackle pollution from storm overflows and how natural flood management and sustainable urban drainage might contribute to improving the health of the river. River health is intimately tied to flow.. both high and low flow. Thank you for reading!

Leave a comment