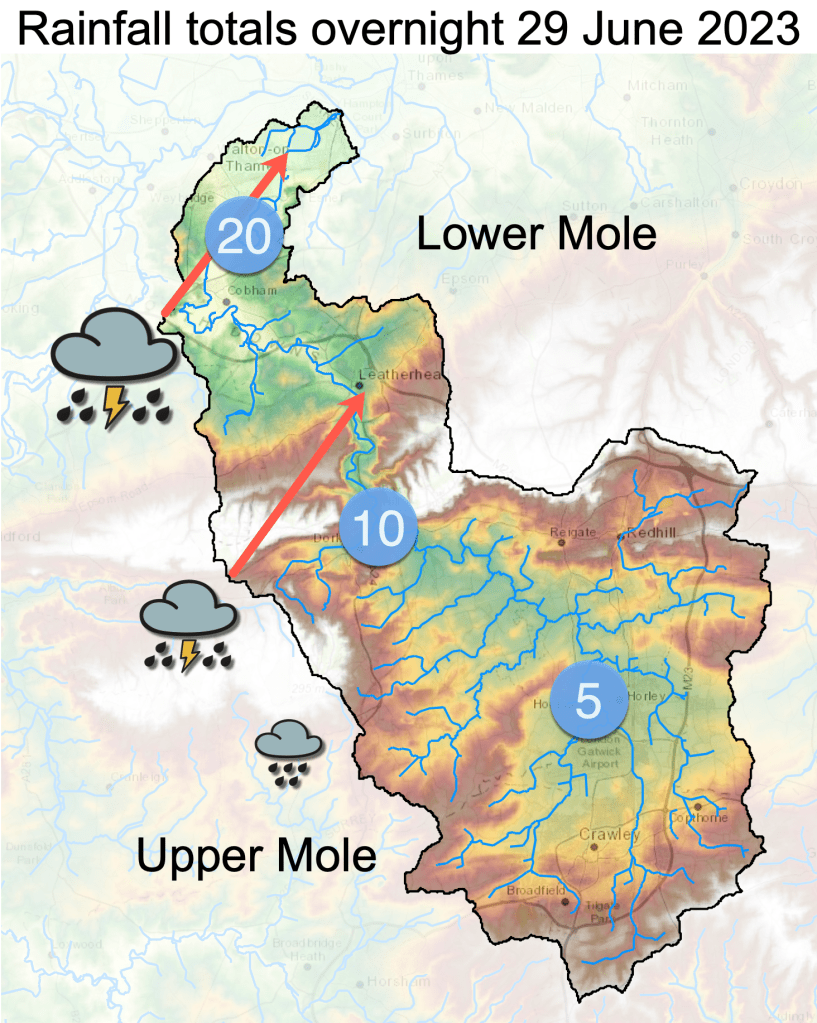

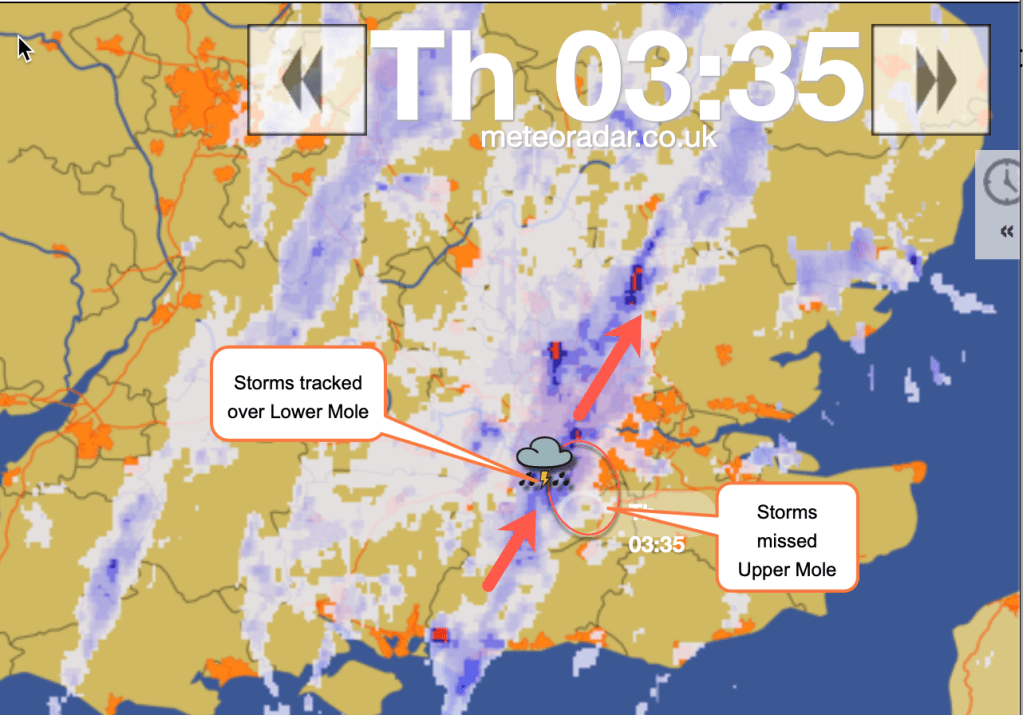

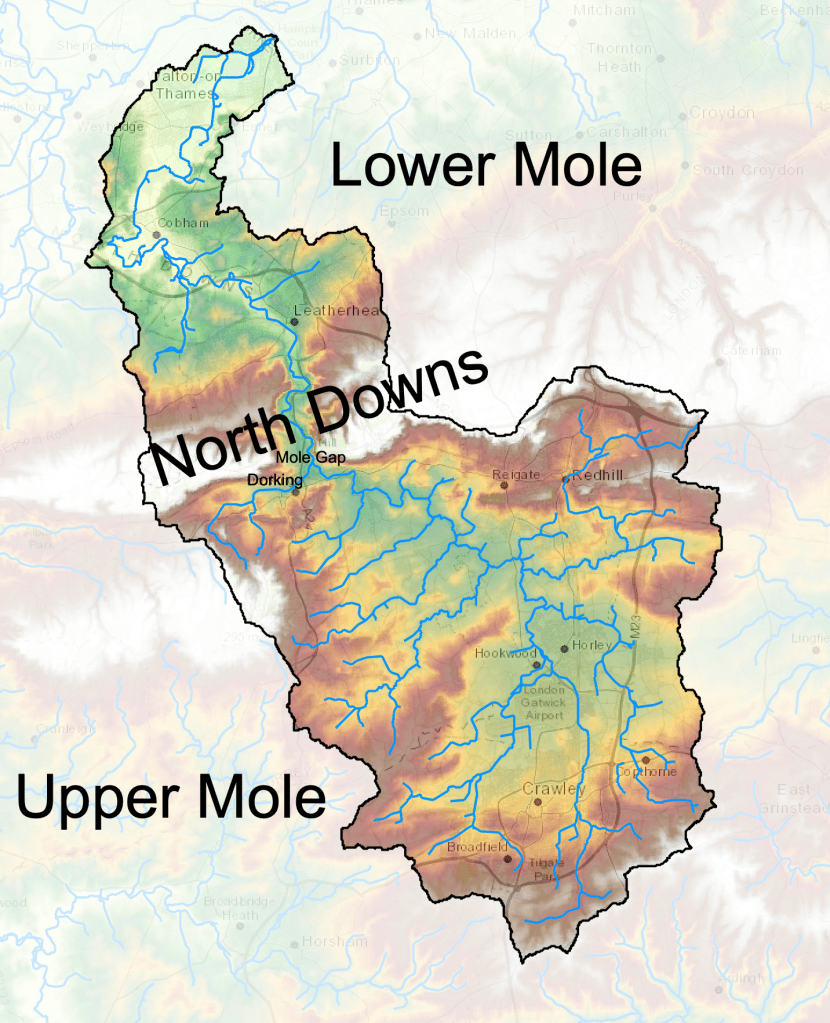

Thunderstorms tracked across the Lower Mole basin in the early hours of 29 June 2023 but they largely missed the Upper Mole. The storms were much heavier over the Lower Mole to the north of the catchment over places like Molesey and Esher. In contrast the Upper Mole catchment to the south of Dorking received much less rain.

The characteristic response of the river serves to highlight the critical importance of protecting vulnerable headwaters in the upper catchment in the pursuit of enhancing sustainable flows and improving water quality, as well as controlling flooding, across the whole Mole catchment.

(Note: if you enjoy these posts I’d be grateful if you please consider donating to the running cost of this site and my research. Please scroll down to find the donate button. Thank you, Simon)

The contrast in rainfall totals over the drainage basin provides a good opportunity to see which parts of the catchment have most control over river response. This thunderstorm event is particularly useful to study because the two previous convective thunderstorms in May and June were both centred over Crawley and caused a distinctively flashy response, dropping similar amounts of rain but over the Upper Mole. On this occasion the tables are turned…the Lower Mole got most rain so this invites us to ask: what happens to the river when most rain falls over the Lower Mole?

What was the pattern of rainfall?

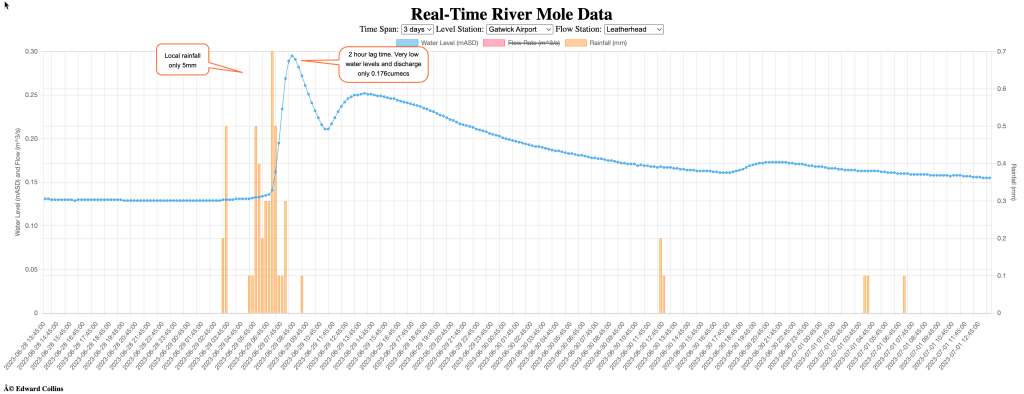

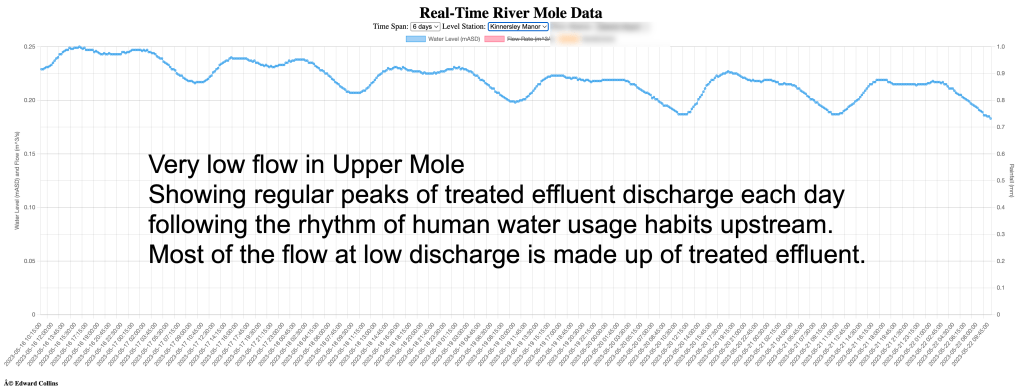

Prior to these overnight storms on 29 June the river was in very low flow, a characteristic of this year when intense convective rainfall events have been separated by prolonged dry periods.

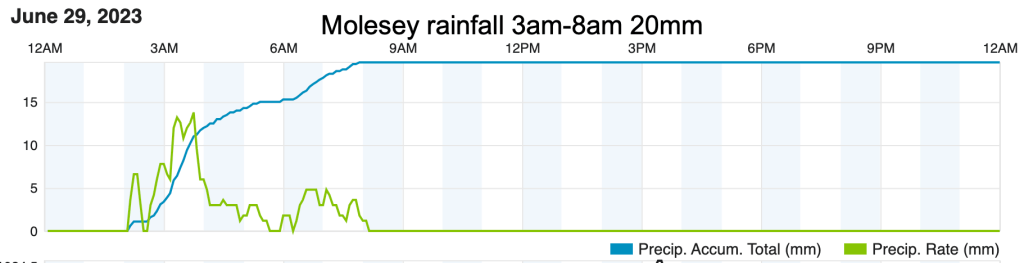

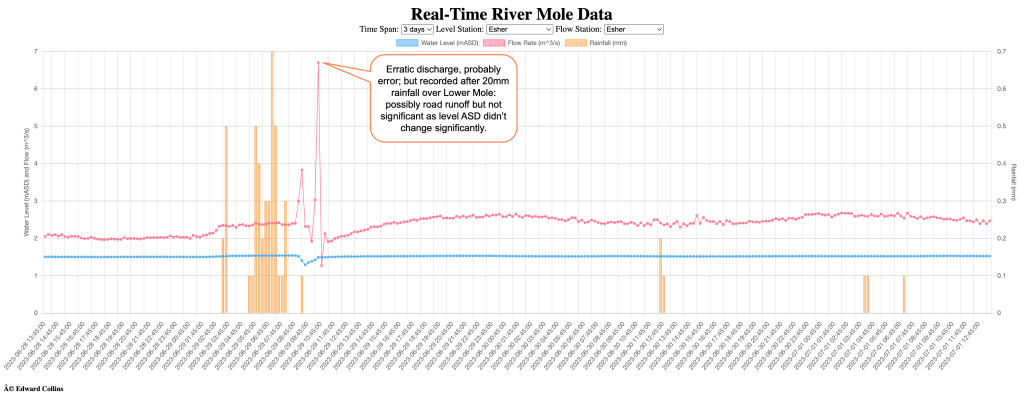

The rainfall chart for Molesey above shows that thunderstorms over the Lower Mole dropped 20mm of rain between around 3am and 8am. This contributed little to total flow apart from a brief initial uptick in discharge representing runoff from roads and drains arriving a few hours after the storm.

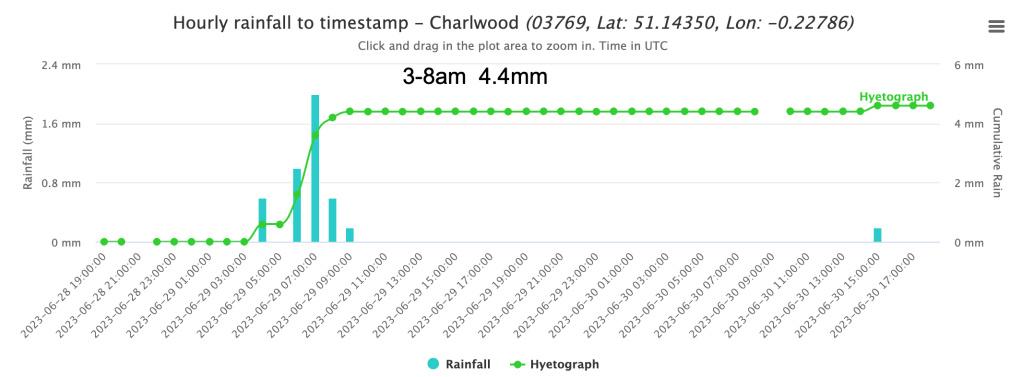

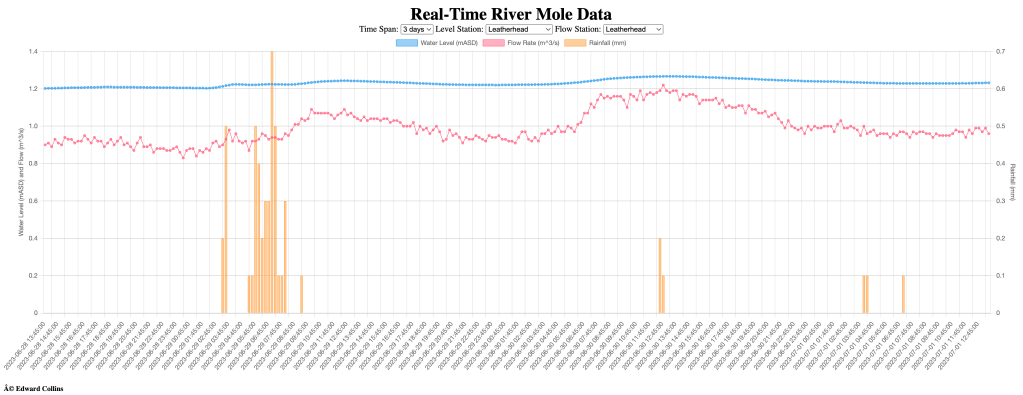

In contrast, the paltry 5mm of rain that fell over the Upper Mole, shown above at the official Charlwood weather station, could be traced far downstream in the hydrograph. The modest rain in the Upper Mole significantly augmented river flow downstream while much heavier rain in the Lower Mole barely shifted river levels locally. It’s rainfall in the Upper Mole that matters to flow.

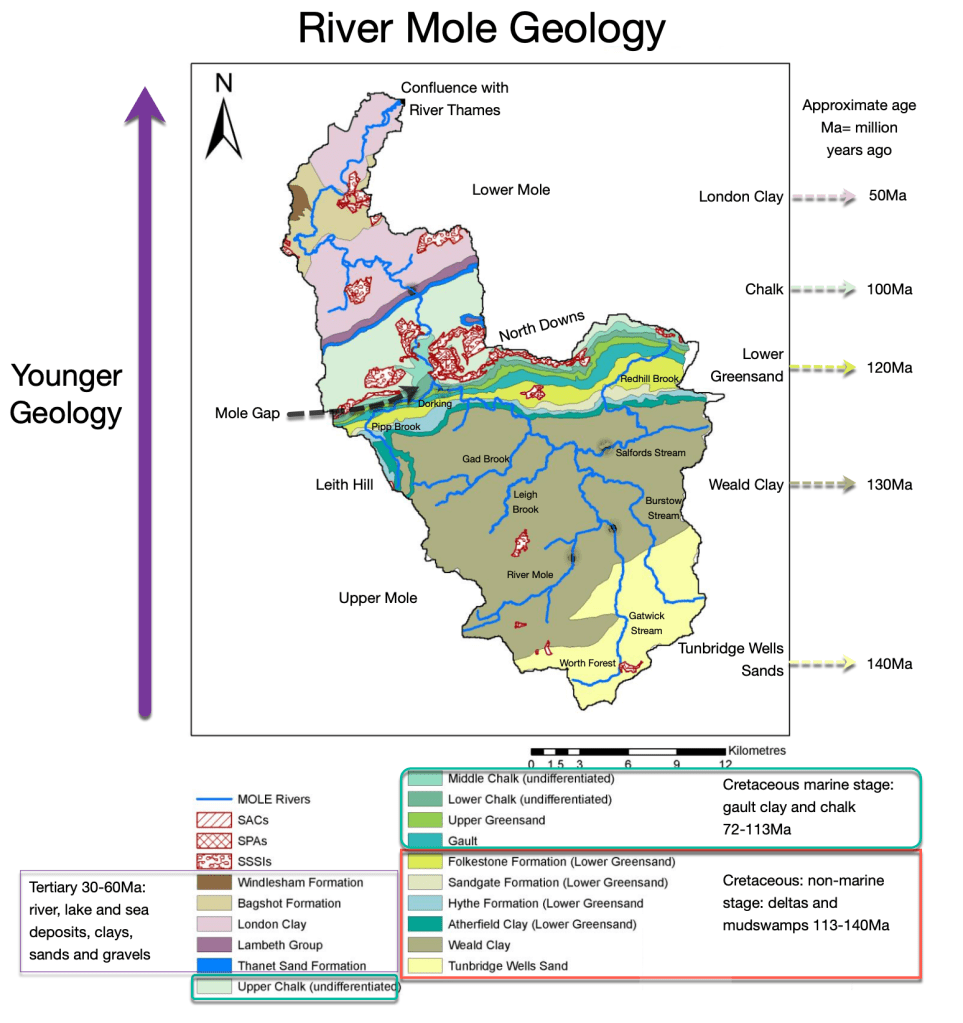

Of course, this characteristic is not unusual in drainage basins where it’s common for a dense network of first order streams near the watershed to collect rainfall which is then delivered further downstream. However, the importance of first order streams and water gathering slopes in the upper catchment area seems to be exaggerated in the Mole catchment due to basin shape and geology. In particular, the Mole has no significant tributaries contributing to flow north of Dorking and the Mole Gap. Furthermore, impermeable geology dominates the Upper Mole, the “collecting basin” of the catchment, while the Lower Mole is broken by the significant band of permeable Chalk in the form of the North Downs. While the contribution of groundwater is not to be ignored, there are few surface streams contributing flow to the Lower Mole other than The Rye from Ashtead and Bookham Brook rise from the chalk Downs. The Lower Mole is deprived of significant additional surface flow north of the Mole Gap. This means that response to any rainfall downstream of the Mole Gap will be significantly muted compared to rain falling over the Upper Mole.

So even the heavy rain of 29 June over the Lower Mole appeared to make little impact on flow, while modest rain over the Upper Mole caused a noticeable response in hydrographs.

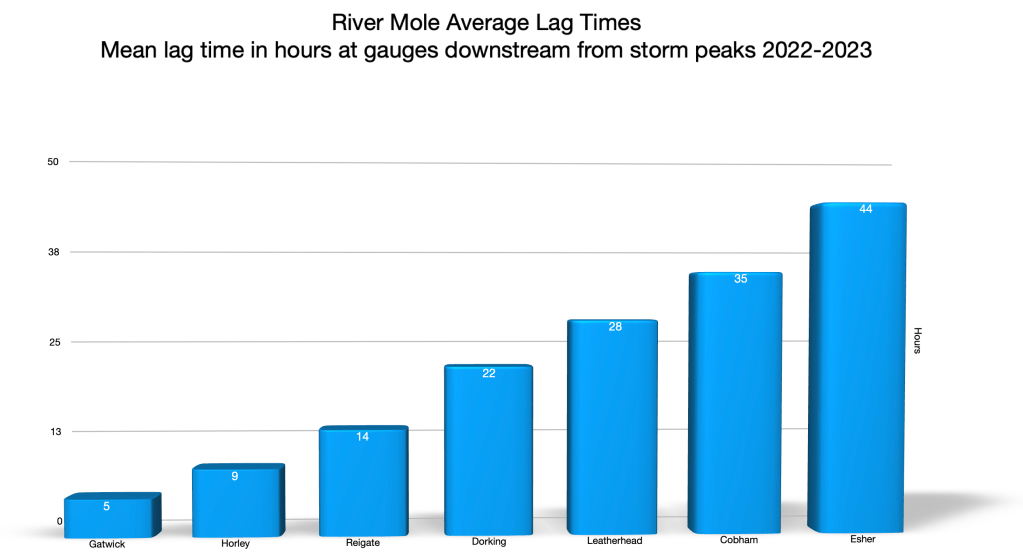

This characteristic, where the flow of the River Mole is heavily dependent on conditions in the Upper Mole, has implications for flood control and water quality. For flood control it gives at least 24 hours of warning before flood peaks from the Upper Mole arrive in the Lower Mole. Furthermore, these hydrological characteristics clearly show the need to protect and enhance sustainable flows in the Upper Mole in times of drought and to mitigate flooding in times of deluge. Natural flood management techniques applied strategically in the Upper Mole headwaters can address both of these issues and provide enormous co-benefits to the whole catchment. In short, what happens in the Upper Mole strongly controls flow and water quality through the populated Lower Mole.

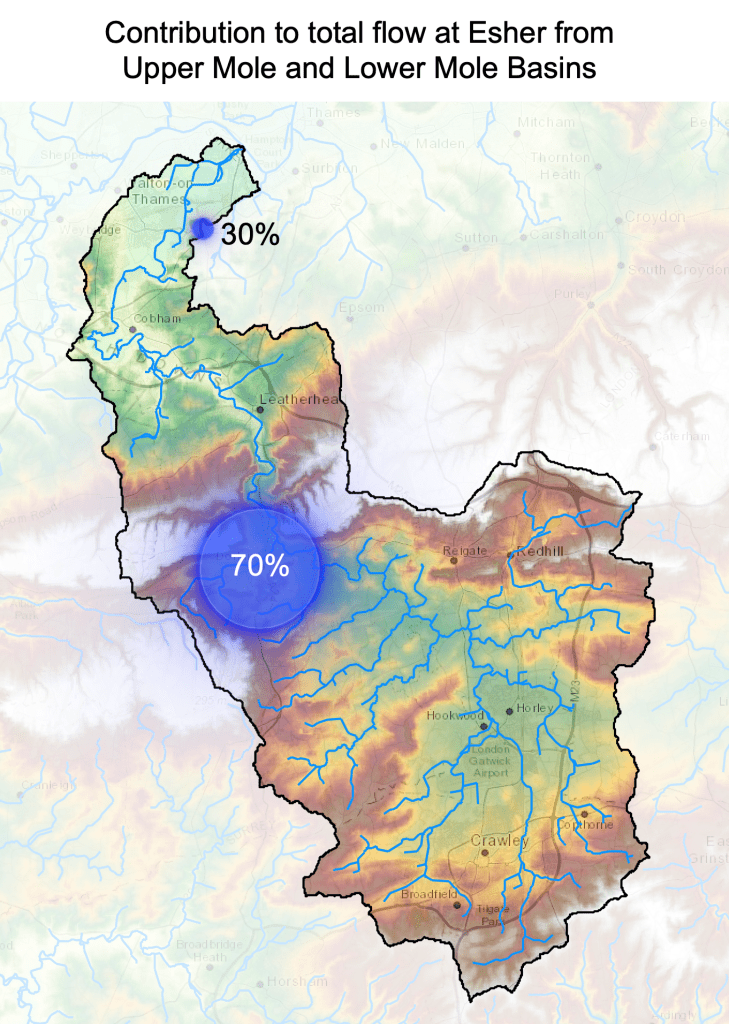

On average, at least 70% of the flow of the Mole discharging into the River Thames at Hampton Court is already in the river at Dorking. Only around 30% additional flow is contributed downstream of the Mole Gap.

This is perhaps even more surprising when you think that Dorking is only half way to the confluence with the Thames. I wonder how this compares to other rivers?

The pattern of rain on 29 June in the radar above shows how the north of the catchment caught thunderstorms tracking towards the NE, while the south of the catchment only caught the edge of these storms.

How did the river respond?

Previous conditions had been dry for several days and discharge was very low. In the Upper Mole the 5mm of rain caused a modest but flashy peak of discharge at Gatwick within 2 hours, a short lag time even for here, but levels remained very low at just 0.3m asd and discharge only 0.175 cumecs. The peak was nevertheless noticeable and can be traced all the way downstream to Esher.

At Leatherhead, where 10mm of rain fell, a modest bump in discharge was recorded around 4 hours after peak rainfall. This first bump is almost certainly local runoff arriving from a brief intense downpour causing overland flow into roads and culverts, possibly also augmenting effluent discharge from treatment works. It is, in any case, too soon to have arrived from further upstream so must be derived locally.

The second, larger “bump” in peak discharge arrived at Leatherhead some 30 hours after the rainfall over Gatwick. This timing conforms to the average lag time for discharge peaks to reach this part of the river from the Upper Mole. So this suggests that the 10mm of rain falling locally over Leatherhead had little impact on discharge while the 5mm of rain over the wider area of the Upper Mole was more discernible as a larger peak flow arriving on time from upstream. The modest rainfall over Upper Mole provided the bulk of flow despite heaviest rain over the Lower Mole.

Further downstream at Esher the changes in discharge at low flow are less clear. In addition, the effect of the Lower Mole Flood Alleviation sluices at low flow means there are often erratic changes in discharge recorded by the Esher flow gauge. Nevertheless, there are subtle changes in discharge that support our theory that rainfall over the Lower Mole has little impact on river discharge. The thunderstorms were particularly heavy over Esher and Molesey and the north of the catchment dropping 20mm in a few hours. The runoff from these storms does appear to register as a sharp change in discharge at Esher 4 hours after peak rainfall. This, like Leatherhead, is probably local overland flow running off from roads and into drains. It might also be additional flow through the treatment works upstream. The sudden increase to 6 cumecs looks suspect as the level hardly changed at all, in fact it decreased temporarily, so actual change may not be recorded reliably here. Nevertheless, flows seem to settle after local overland flow arrives and the discharge at Esher eventually peaks at around 2:30am on 1 July some 44 hours after the peak rainfall. This again conforms to average lag time for this location and so would seem to equate to the expected arrival of the peak discharge from the modest rainfall over the Upper Mole.

So the results of this rainfall event, with heavy rain over the Lower Mole and light rain over the Upper Mole, seem to support our theory that rainfall over the Lower Mole has little impact on discharge of the main river while it is events in the Upper Mole that control flow in the river.

The reasons for this are clear: the wider, rounded shape of the Upper Mole contributes to the efficient capture of rainfall and the high drainage density (large number of water courses and tributaries feeding the main river) across impermeable clay also ensures that storm discharge is quickly transferred by first order streams and water courses to the main channel in relatively short order. The Upper Mole catchment at Horley is some 15-20km wide while the Lower Mole at Leatherhead is 10km and at Cobham only 5km wide. This means there is far less area for rainfall capture in the Lower Mole. The geology also means that, through the Mole Gap, there are no tributaries and to the north of the Chalk Downs there are only a handful of minor tributaries such as the Rye, Bookham Brook and the Dead River. These contribute little to additional flow in the River Mole.

It is worth remembering that, at low flow conditions, little water in the River Mole is base flow (i.e draining naturally from permeable rocks and soil). As much of the catchment is impermeable, at low flow, most water in the river is treated effluent and much of that has been abstracted from groundwater in the chalk aquifer. Indeed, some estimates suggest some 75% of the flow of the Mole can comprise treated effluent from the big treatment works at Crawley, Horley, Earlswood and Dorking, Leatherhead and Esher. Nevertheless, when it rains, there is immediate addition of additional flow from rainwater runoff and that is what we are really discussing here.

An additional complexity to Mole discharge is the effect of the river passing over chalk through the Mole Gap. As the river passes over the chalk geology there is a measurable loss of flow into the chalk through the famous swallow holes. Downstream, as the river passes back over London Clay around Leatherhead, the groundwater resurges again from springs at Fetcham and Leatherhead. Subsequent posts will explore the total contributions these make. Suffice to say, at this stage, the net additional contribution to discharge of resurgent springs to the total flow of the Mole is likely to be small. My hunch is that the complex plumbing through the Mole Gap simply pipes the water from swallow holes at Mickleham and Norbury to rejoin the river at Fetcham. They therefore contribute little additional groundwater but rather simply reroute river water from further upstream into resurgent springs which emerge at Fetcham and Leatherhead. This is just a working theory for now.

To conclude, most of the flow in the River Mole is collected from rainfall in the Upper Mole catchment. On average some 70% of the flow that joins the Thames at Hampton Court is already “in the river” by Dorking. Little additional discharge is added downstream of the Mole Gap. So even heavy rain over the Lower Mole makes little impact on river discharge. This has enormous implications for the future management of the whole River Mole catchment.

I hope you enjoyed this post. Please consider donating to help me run the site and continue to write about our much loved River Mole. Click the donate button below. Many thanks indeed.

Leave a comment