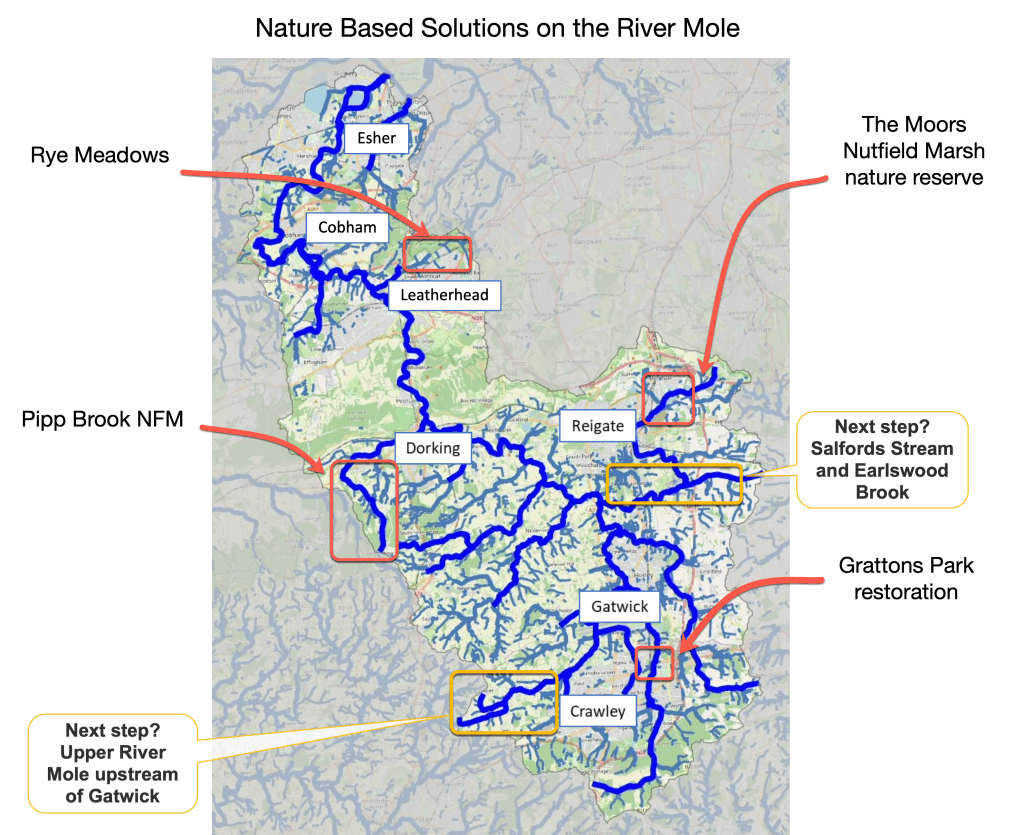

I recently had the great pleasure of joining a group from the Environment Agency on a site visit to a Natural Flood Management Scheme (NFM) in the River Mole catchment. There are very few NFM schemes in the Mole catchment (more on that later) so I was delighted to get the opportunity to visit the scheme. My sincere thanks go to Ben Tonkin and Karrie Doust at the EA for arranging this inspiring trip. This post arises from that trip and goes beyond to consider where else in the Mole catchment might benefit from nature based solutions such as natural flood management. It’s quite a long read, hope you enjoy it!

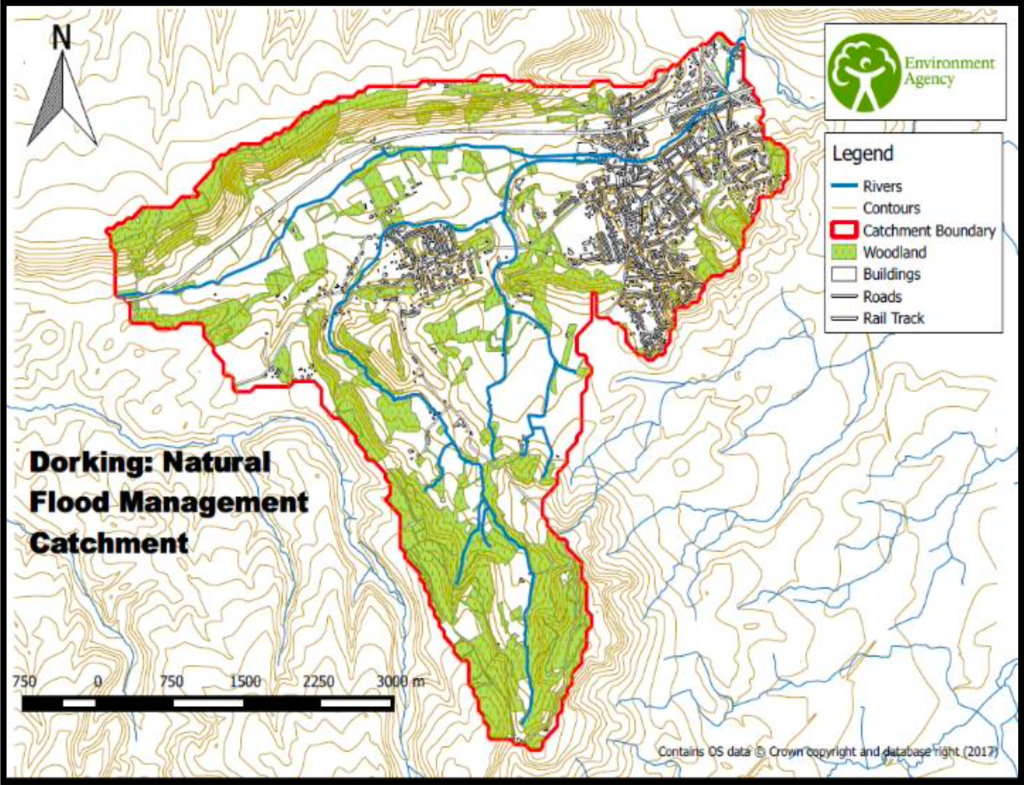

Ben is from the EA who is also a PhD student at the University of Surrey in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. Ben’s PhD research is modelling the effectiveness of leaky dams to inform practice for future natural flood risk management. His focus is on hydraulic modelling of 30+ leaky dams installed by the Environment Agency on the Pipp Brook above Dorking. The project began in 2015 and construction of the NFM scheme was completed in November 2019. The whole project is a 10 year catchment monitoring programme to assess how the dams perform and inform modelling for future NFM schemes.

In this post, I review flood management in the Mole catchment as it is now, including other nature based schemes; I also look at the benefits of Natural Flood Management and how they can contribute to flood control, reduction of pollution and increase resilience to drought; I also review NFM techniques, including benefits and potential problems, and, finally, I make suggestions as to where in the Mole catchment future NFM techniques might be located. It’s a long read!

The current public narrative on rivers is understandably focussed on sewage pollution. However, this risks hiding the numerous other problems faced by our rivers such as excessive runoff caused by development, barriers to fish passage, invasive species and agricultural and urban pollution amongst many other problems. Natural Flood Management and Sustainable Urban Drainage and a Catchment Based Approach are key parts of solving these wider issues sustainably.

As usual, I’ve used numerous sources to research and write this. A full list of references can be found at the end. I’d like particularly to thank Emma Wren, Natural Flood Management Lead at Mott Macdonald, for the kind permission to use her beautifully drawn illustrations of the different NFM techniques published in the NFM Manual Ciria 2022. All photos are my own, unless otherwise indicated.

What are NFMs?

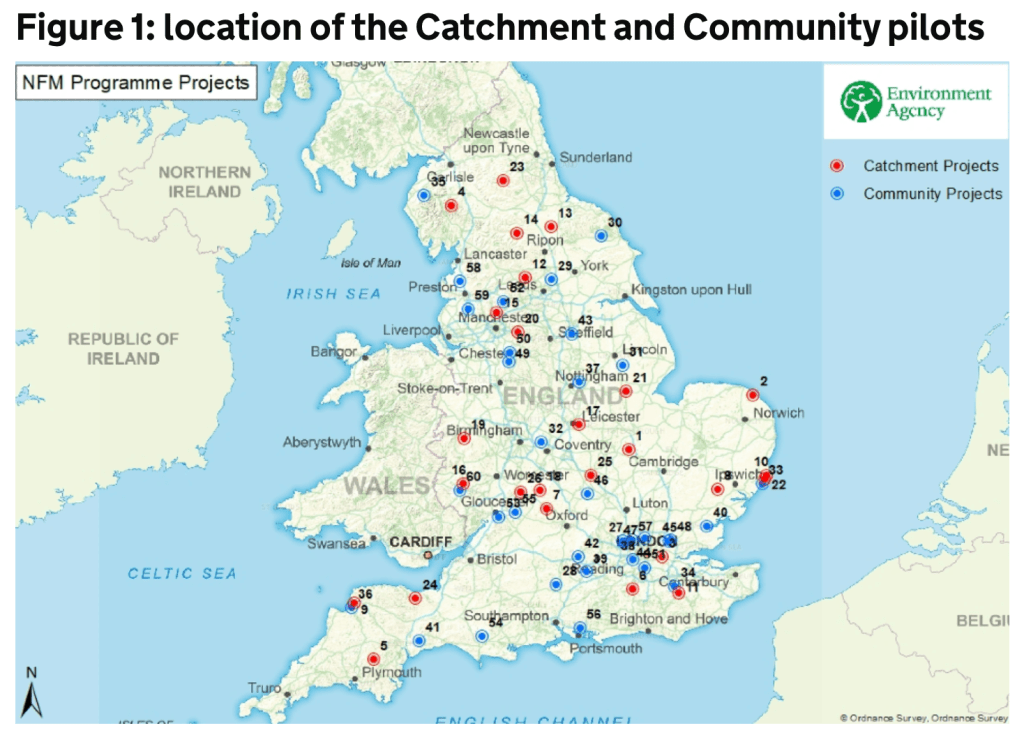

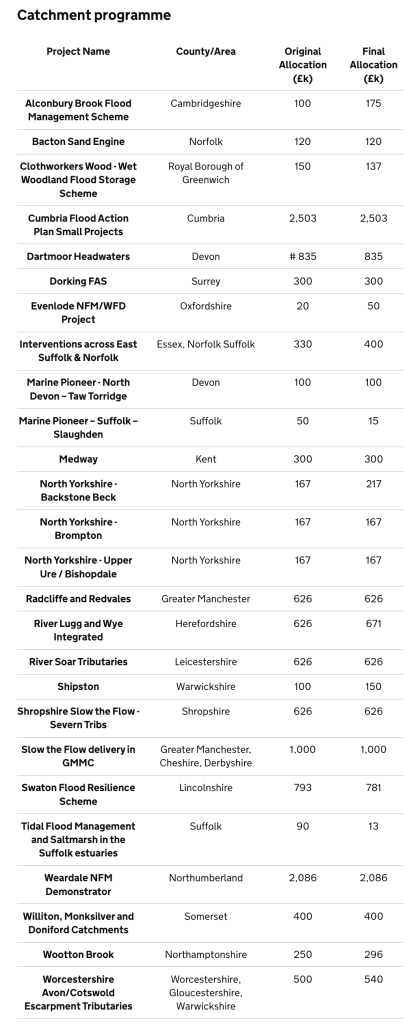

The PippBrook leaky dams project is one of 60 Natural Flood Management pilots across England. The Government invested £15 million into these programmes.

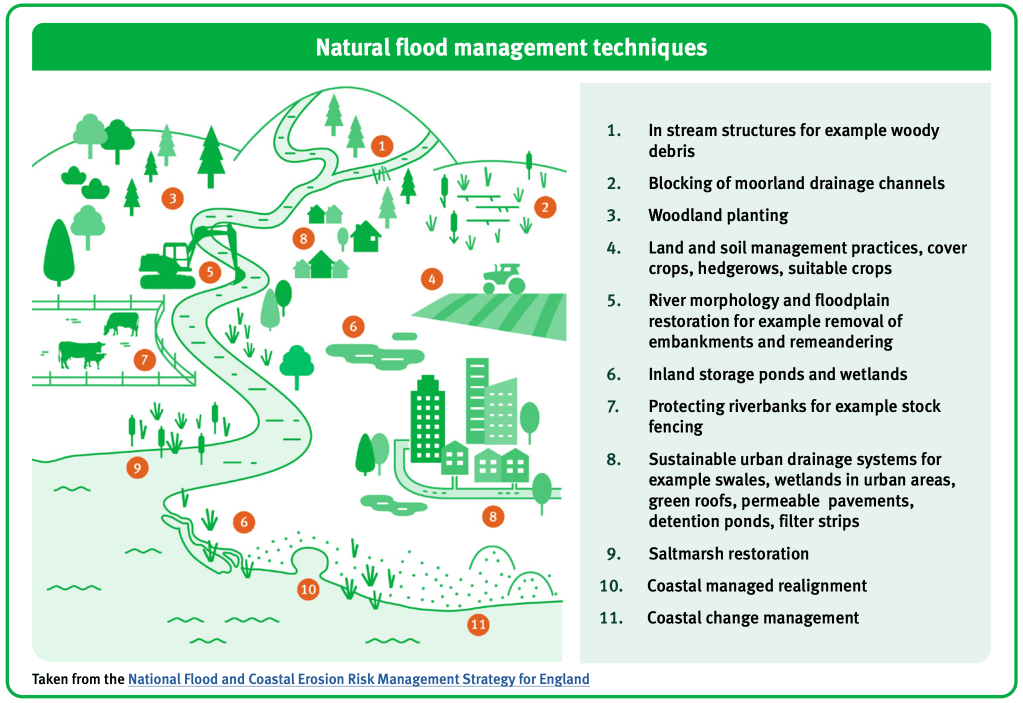

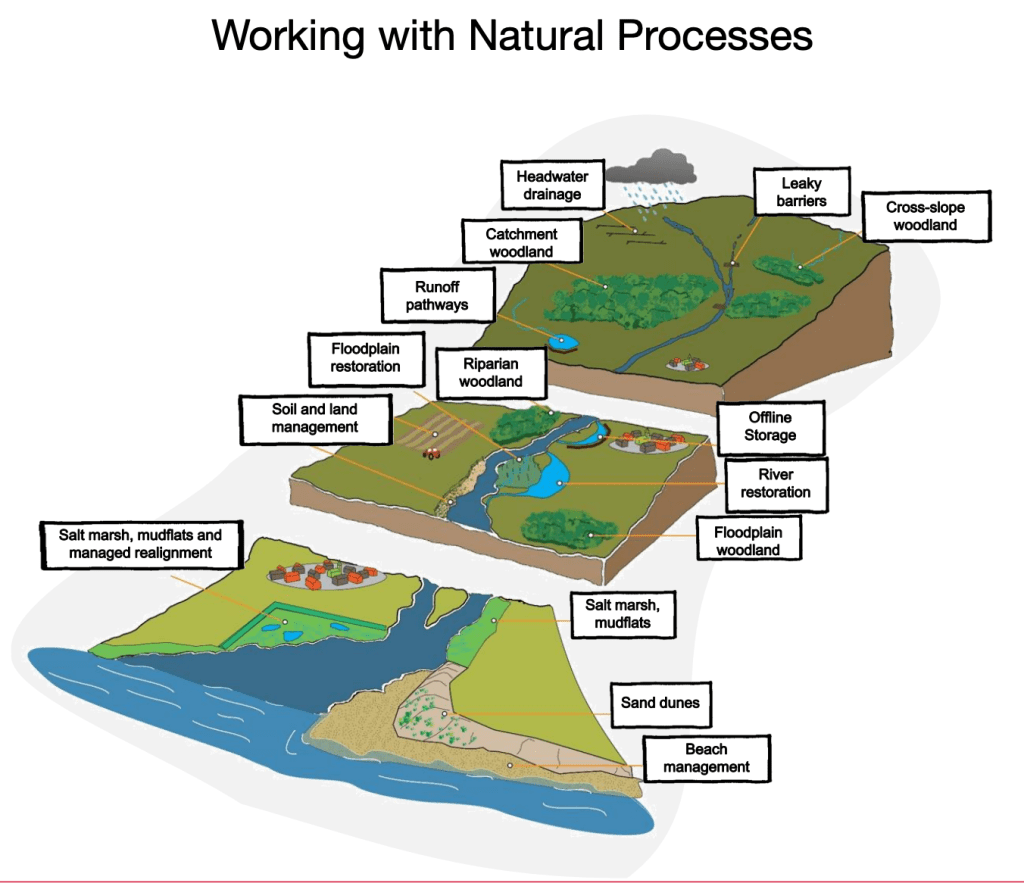

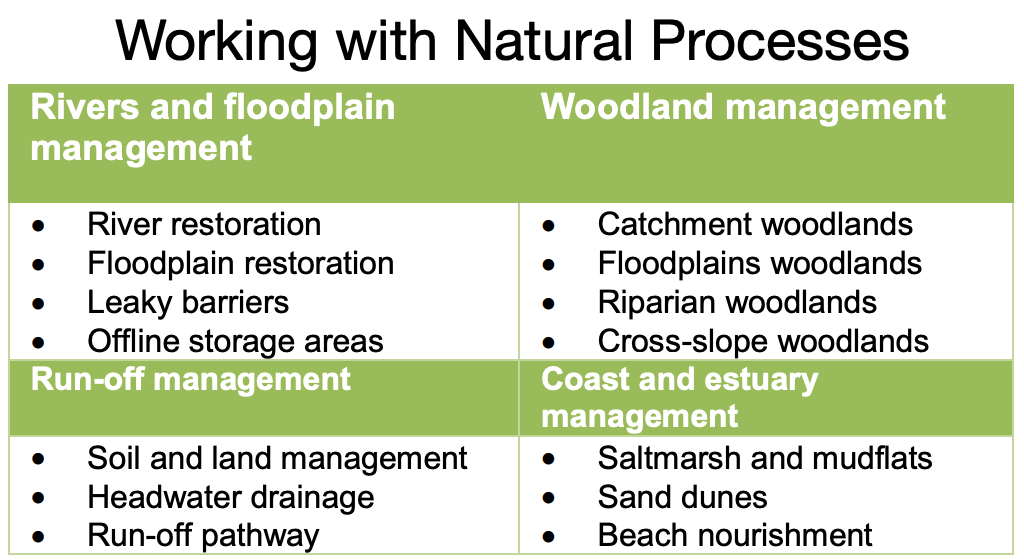

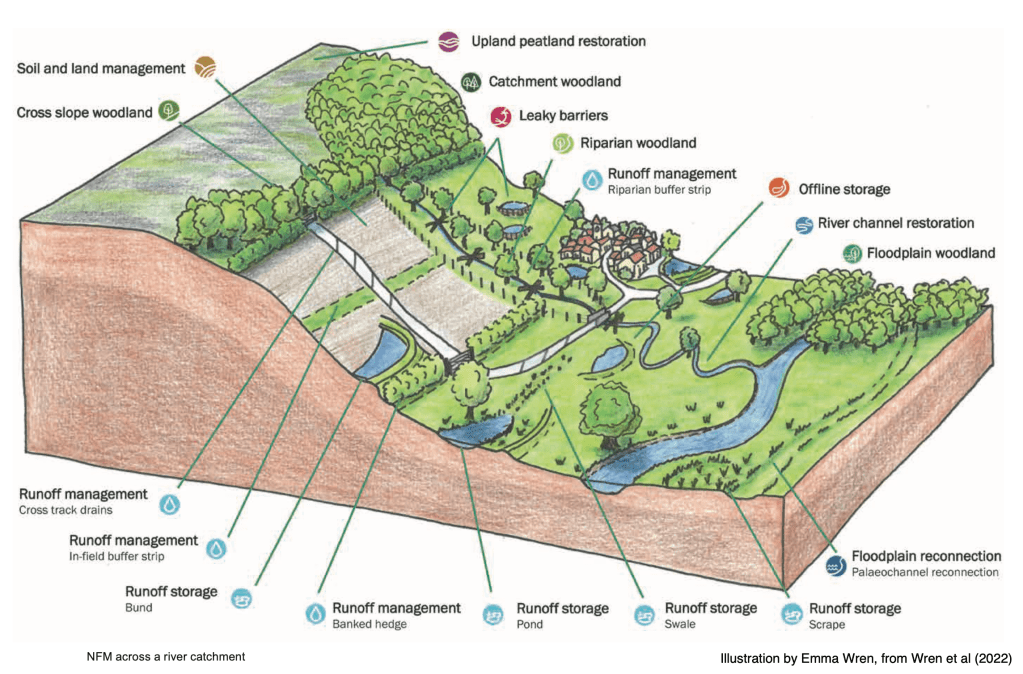

Natural Flood Management is part of a wider approach called “Working with Natural Processes”. This approach seeks to reduce flood risk and protect and restore natural functions of catchments, floodplains and rivers. The overall aim of these nature based solutions is to find more sustainable, some might also say cheaper, ways to reduce flooding by slowing runoff and storing more water in landscapes.

By slowing the flow and storing water in the landscape NFMs can build resilience against flooding and drought. Whilst they will not be the solution everywhere or in isolation, they can contribute to flood protection if part of a catchment based approach. There is a growing menu of flood management solutions including NFMs, SuDS, mobile defences and more traditional hard management solutions in vulnerable places. The future of flood management is to identify the right selection of measures for the benefit of the whole catchment.

As NFMs can be cheaper than more traditional flood protection approaches, it’s not surprising that the Government is keen to promote them! Where possible, NFMs are being encouraged in preference to and/or in combination with expensive, carbon emitting, hard engineering techniques. Greater use of NFM is a feature of the government’s Flood and Coastal Erosion Risk Management: Policy Statement 2021 which states:

The power of nature will be part of our solution to tackling flood and coastal erosion risks. We will double the number of government funded projects which include nature-based solutions to reduce flood and coastal erosion risk.

Civil engineering firms also research and promote the use of NFMs where appropriate:

We can help alleviate flood risks more sustainably if we work with natural processes to manage river catchments. …. In other words, flooding by design, rather than by default.

Emma Wren, Principal Hydrologist, Mott-Macdonald

Part of the attractiveness of NFMs is that they provide numerous co-benefits including those associated with biodiversity net gain and net-zero targets. Co-benefits include improving habitats and biodiversity, reducing pollution, increasing water quality and availability of drinking water, and improving health and wellbeing. NFMs can also capture and store carbon, contributing to climate change mitigation and net-zero targets.

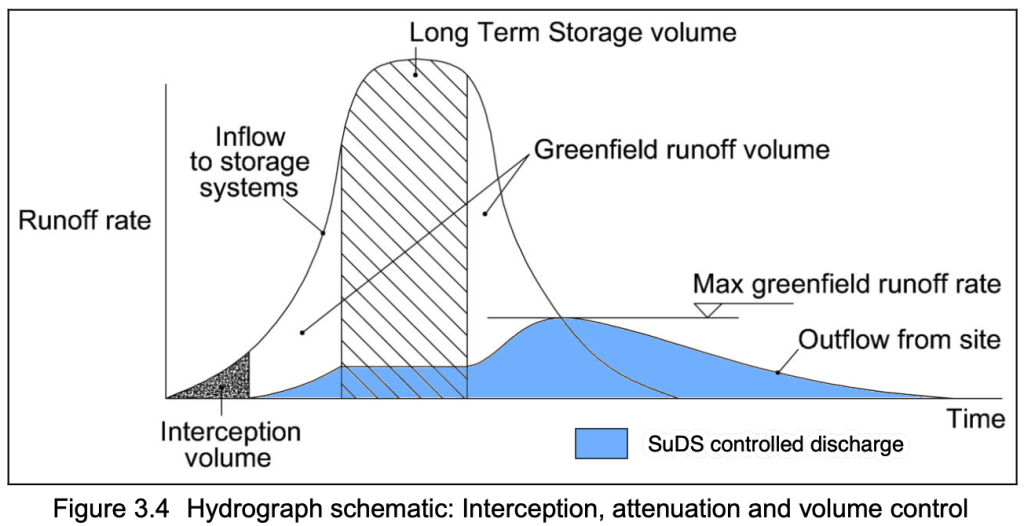

There is considerable overlap between Sustainable Urban Drainage Schemes (SuDS) and NFMs. They both seek to slow the flow. Sarah Bentley, Thames Water CEO, called SuDS methods “spongifying” the urban environment by employing techniques such as planters and rainwater butts, permeable pavements, ponds, swales and scrapes. The aim of SuDS is to minimise surface runoff and store the additional volume of discharge running off new developments.

So, while SuDS are designed to reduce runoff and mitigate the flood impact of urban developments, Natural Flood Management Schemes are usually installed in more rural catchments, often in upper courses of streams, and most often upstream of significant urban development.

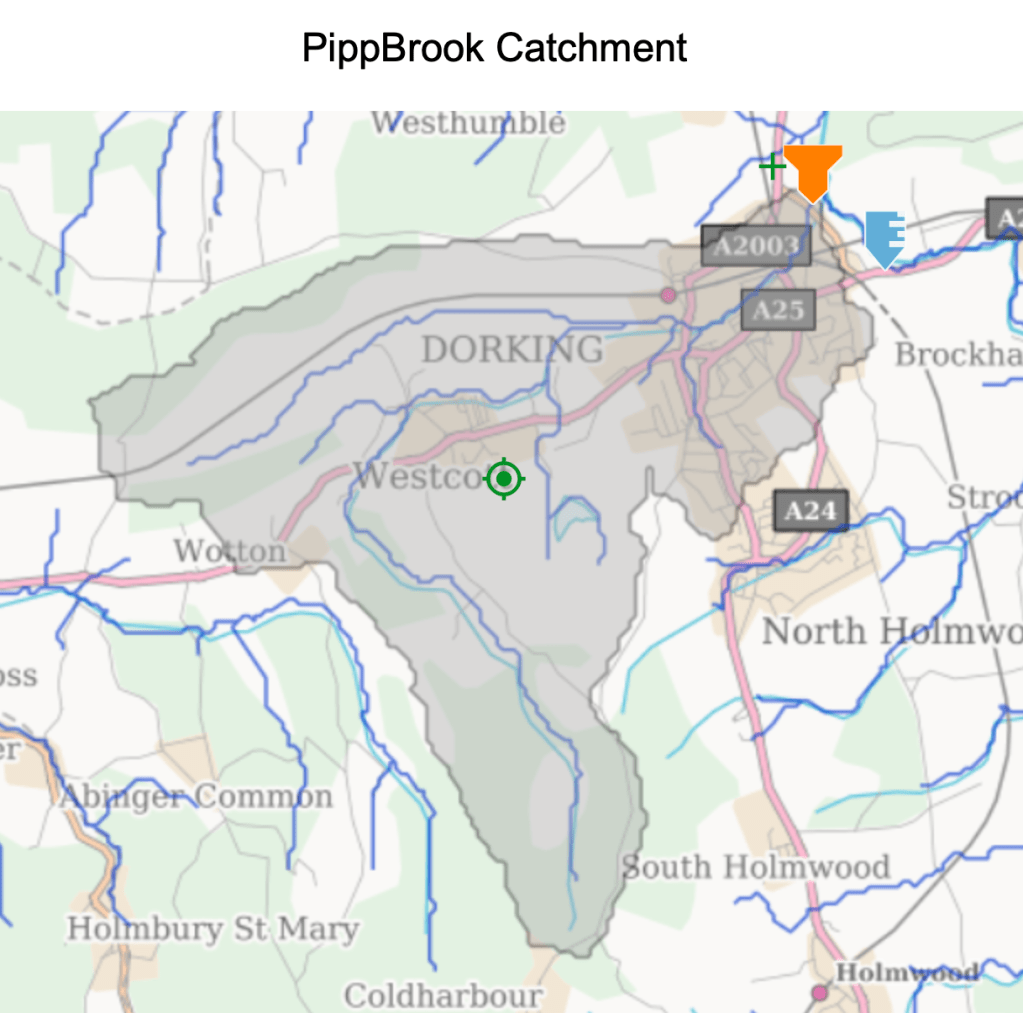

Where is the Pipp Brook NFM scheme?

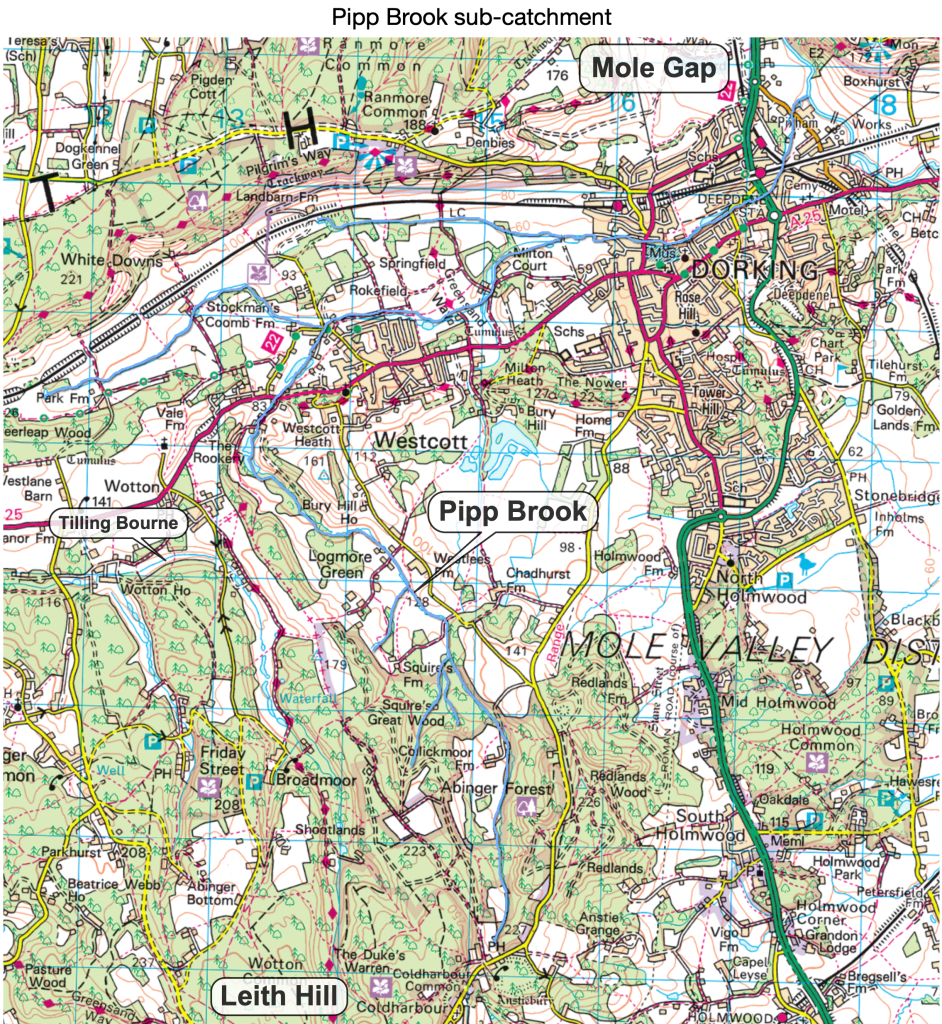

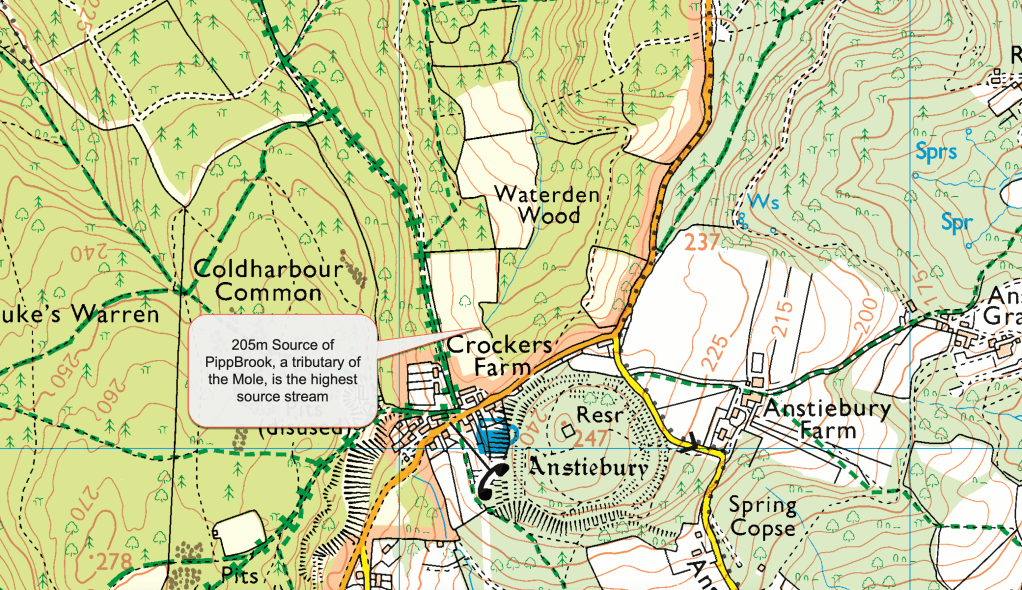

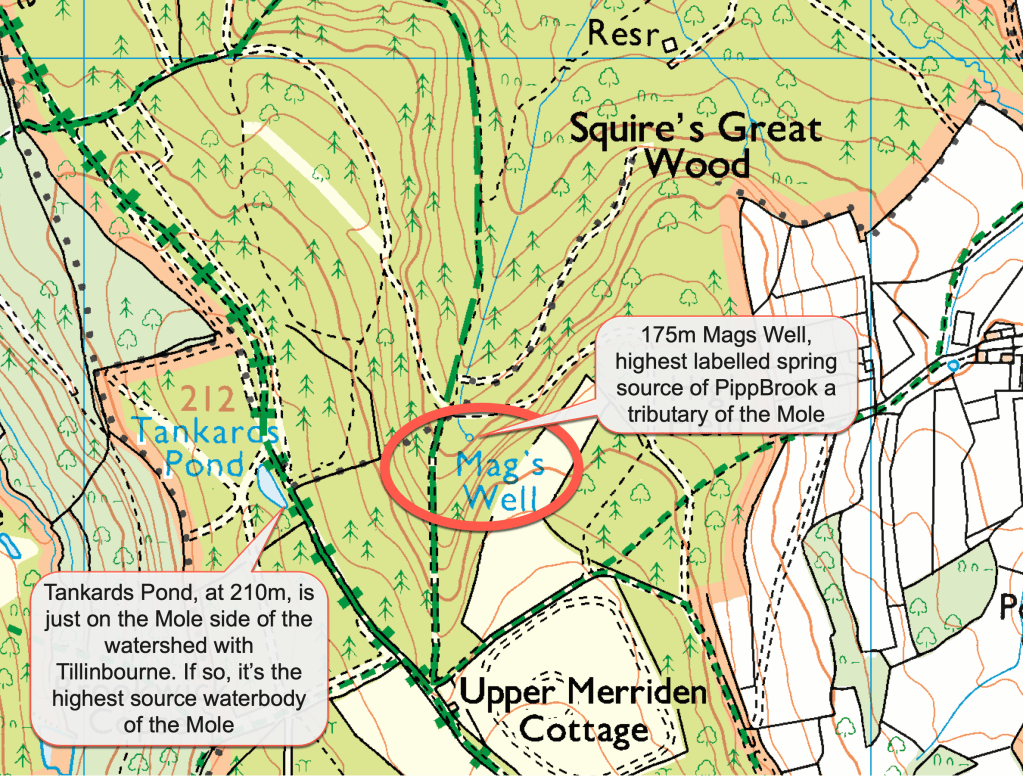

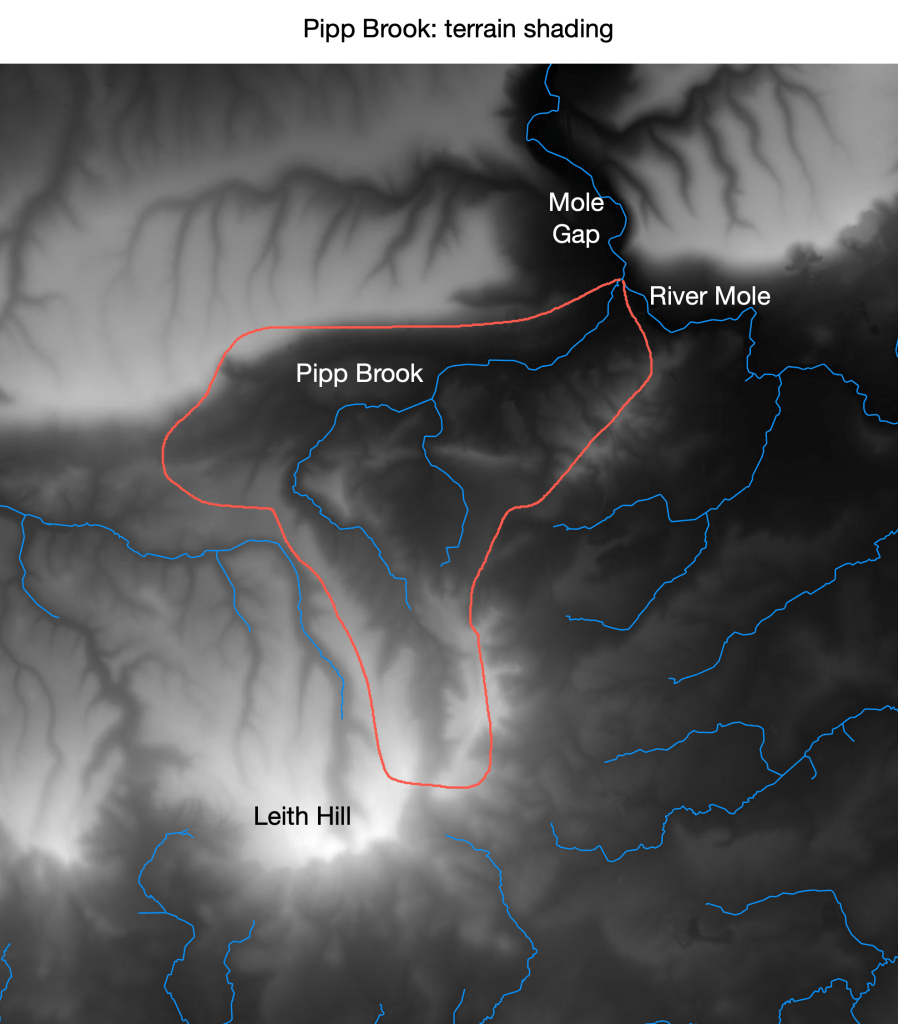

Pipp Brook is a small tributary of the River Mole. It rises in a wooded valley SW of Dorking, 1km NW of Leith Hill and just north of Coldharbour village. It is within the Surrey Hills AONB and is a beautiful area of hills, woods and heaths.

From it’s source, Pipp Brook flows north west from the Greensand Hills into the clay Vale of Holmesdale at the foot of the chalk scarp, where it turns sharply east, flowing through Dorking to join the River Mole at the mouth of the Mole Gap below Box Hill. Roughly half the catchment is rural, forests and farmland, while the lower course of Pipp Brook is urban, flowing through Dorking and its suburbs.

Pipp Brook lays claim to being the most elevated tributary on the Mole catchment, rising at the highest altitude of any source at just over 200m.

Mag’s Well, another source of the Pipp Brook, has an air of mystery as the iron rich waters were said to be a source of healing during the 19th Century. Coldharbour may have become a spa town!

The relief and terrain maps above and below show the interesting drainage pattern and relief of the area. The contour map above shows the steep gradient of the upper course with a curious asymmetry to the valley cross section shortly before reaching the broad Vale of Holmesdale that runs east-west. It also shows the neighbouring Tillingbourne stream which is a tributary of the River Wey so outside the Mole catchment. The lighter shades on the terrain map below show higher elevation with Leith Hill almost glowing as the highest point. Sadly, the summit of Leith Hill, at 294m, lies outside the Mole catchment, sitting on the watershed between tributaries of the River Arun and River Wey. The highest elevation hereabouts in the Mole catchment is 270m on Coldharbour Common

The Mole Gap shows up clearly as a dramatic cut through the Chalk Downs with attendant consequent dry valleys lying at right angles to the Mole. It’s interesting to note that the Pipp Brook is almost “through” valley, with a wind gap passing through Coldharbour marking the watershed between the Mole and Arun catchments.

The confluence of Pipp Brook with the Mole at Dorking lies at 37m, so the Pipp Brook has one of the steepest descents of any streams in the catchment of 168m over 8.7km. It is an ideal location for a Natural Flood Management Scheme.

Why do we need NFMs in the Mole catchment (and everywhere!)?

Before we tour the leaky dams, let’s review flood defences in the Mole catchment and ask why we need NFMs at all. This will put the Pipp Brook NFM in context.

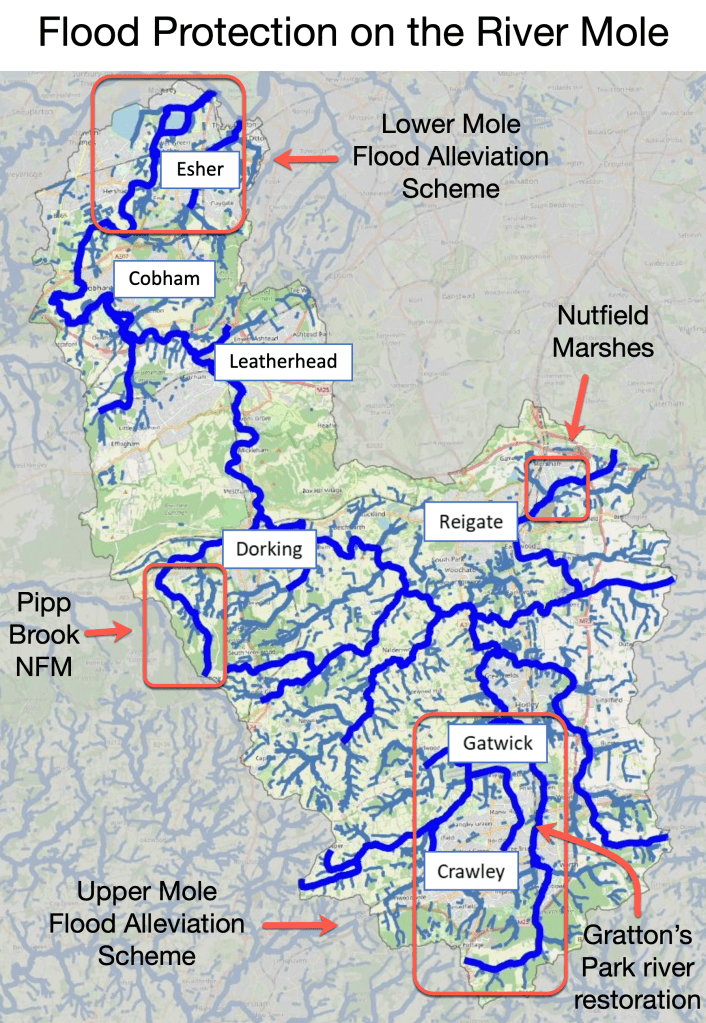

The two big flood protection schemes in the Mole catchment are traditional “hard engineering solutions” which involve a combination of elements such as sluices, dams, penstocks and artificial attenuation storage. These are costly engineering projects, involve significant carbon emissions throughout their life span and do little to address the biodiversity crisis. They do, however, provide reliable flood protection up to 1:100 year floods or more in the case of the Lower Mole scheme. The Mole catchment only has a handful of “soft” or nature based management solutions and the Pipp Brook scheme is the only one of these which has leaky dams, arguably the defining element of NFMs.

The two “traditional hard engineering” flood alleviation schemes are the Upper Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme (UMFAS) and the Lower Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme (LMFAS).

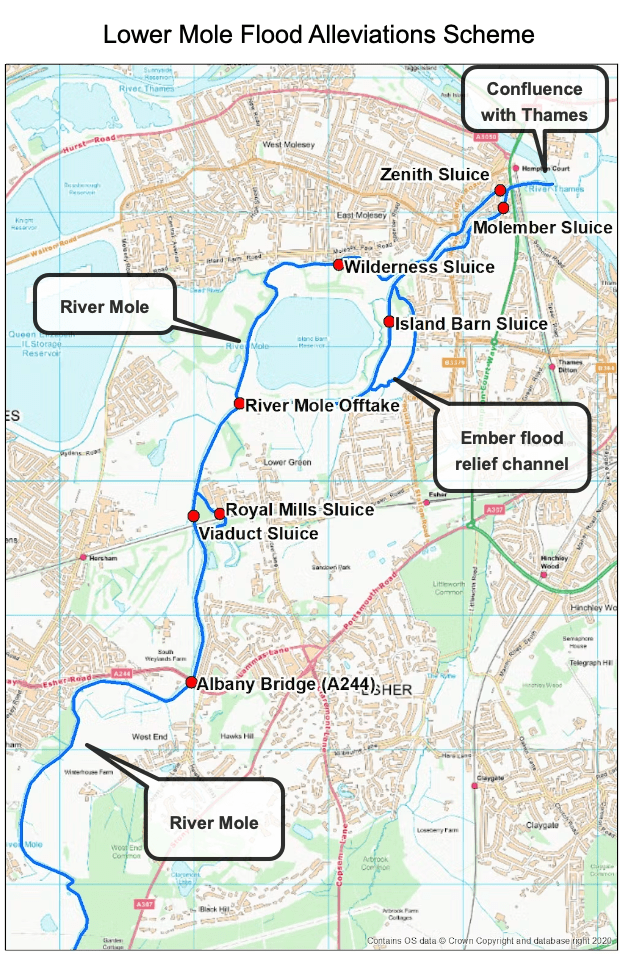

The Lower Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme (LMFAS) is between Esher and Molesey. It comprises a series of large sluices with a flood relief channel, called the River Ember.

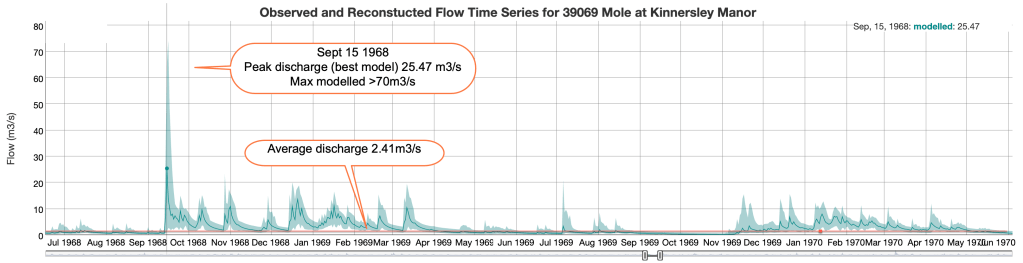

The LMFAS was completed in the 1980s and was built in response to the devastating 1968 Mole 200 year flood which inundated areas downstream of Hersham. Reconstructed flows for the Upper Mole show discharge exceeded 70m³/s compared to the average discharge of 2.4m³/s.

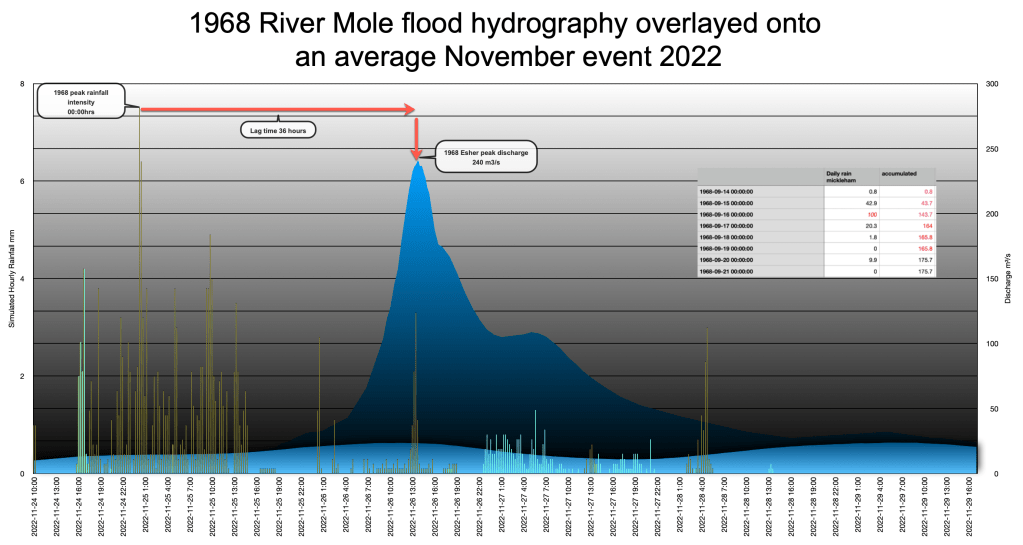

Discharge on the Lower Mole during this 1:200 year storm were over 240m³/s, a phenomenal discharge for the river, more than three times the flow of the Thames through London. Large areas of the Lower Mole were flooded as a result of more than 100mm of rain falling in 24 hours and over 160mm of rain falling over 3 days. The hydrograph below shows a reconstruction of the extraordinary 1968 discharge overlayed onto an average wet period in November 2022 when the river was frequently at bankfull flow.

The LMFAS was needed to address rare but high volume floods and has performed well over the years, protecting the Lower Mole area against all flooding since. However, the LMFAS is now at the end of its life and urgently needs replacing because the sluices and gates are 40 years old, well beyond their design life and no longer fit for purpose (in other words they might fail to operate as designed).

This is a story for another post but, briefly, some of the proposed replacement schemes involve working with nature more by removing hard engineering and encouraging a more natural channel to manage the flow. Although not an NFM solution as such, these alternative approaches show the importance of considering sustainable solutions that will be affordable, low carbon and effective in to the distant future.

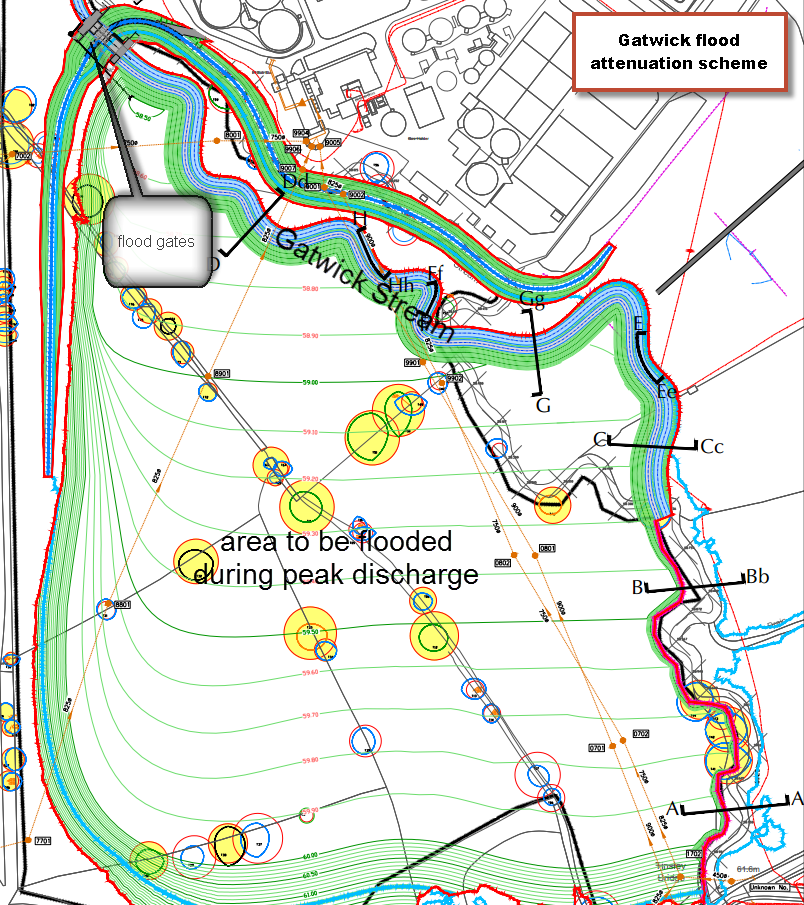

The Upper Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme is more recent, comprising a series of attenuation structures and dams in the Upper Mole catchment located on tributaries upstream of Gatwick airport, in particular on the Gatwick Stream

The UMFAS is a scheme part funded by Gatwick airport and partly in response to the flooding in 2013. It includes hard engineering schemes such as Clay Lake, Worth attenuation scheme, Tilgate Lake and the Gatwick Stream FAS.

These alleviation schemes were designed to protect against a 1% annual exceedence probability (AEP), also known as the 1:100 year flood. However, climate change and development has probably lowered the flood protection to 1:75 year flood now. Whilst these are “hard engineering” schemes, some elements of flood management around Gatwick have enhanced biodiversity through improvements on the realigned sections including channel restoration along the Gatwick Stream.

NFM schemes could be ideally placed in the Upper Mole catchment for a number of reasons:

The UMFAS only covers the Gatwick Stream. The Upper Mole itself, south of the airport, has no dedicated flood protection as such. The Upper Mole is also the scene of extensive residential development including hundreds of new homes being built on sites in the Bewbush Brook catchment as well as a highly contentious application by Homes England to build 10,000 houses on greenfield sites on the Mole flood plain near Ifield. Whilst SuDS are now mandatory for all residential development, the River Mole south of Gatwick is an area that would benefit from NFMs and the rural wooded areas would be an excellent potential site for such schemes.

The LMFAS is at the end of it’s life and some replacement options include sustainable and low carbon technology. An NFM scheme will not offer the protection to the Lower Mole required but could contribute by attenuating storm runoff upstream.

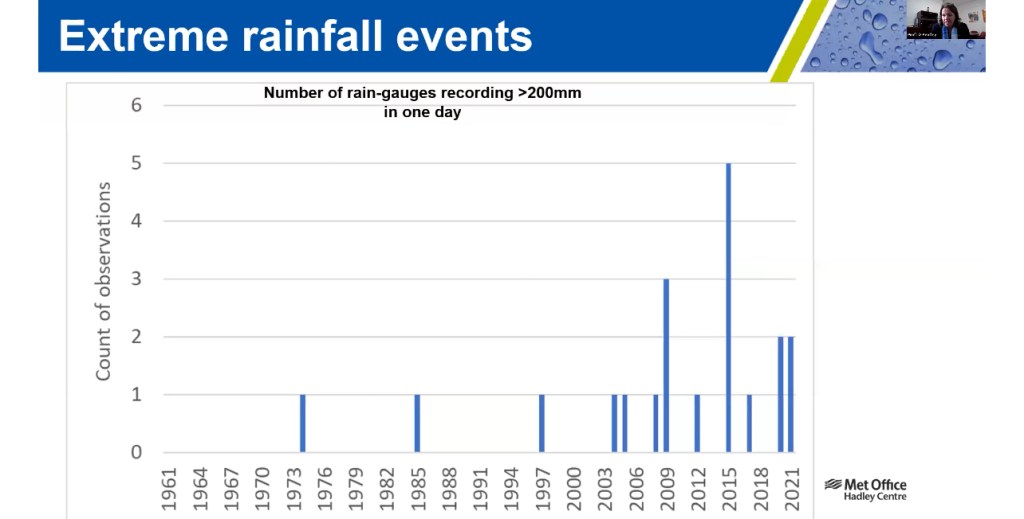

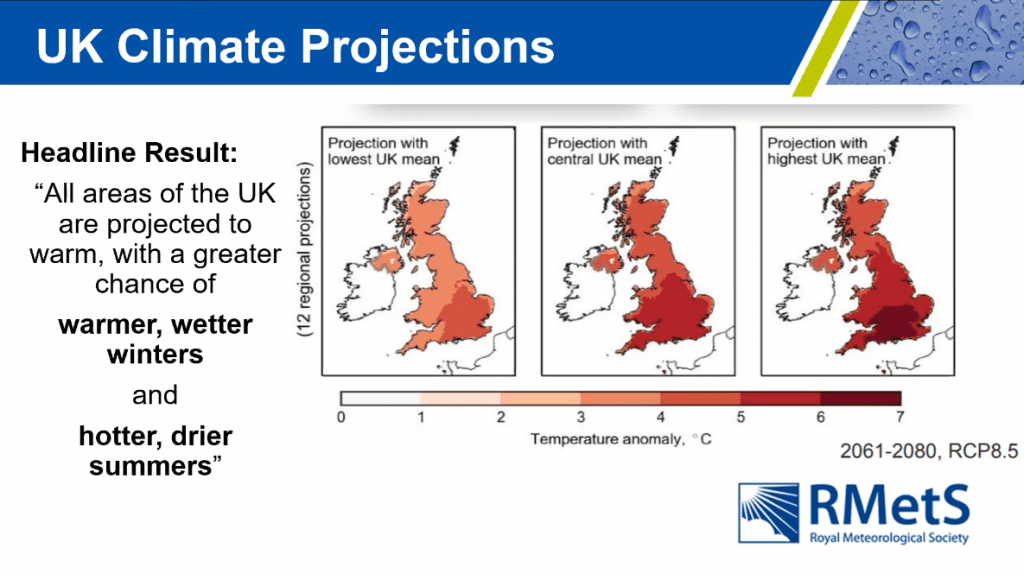

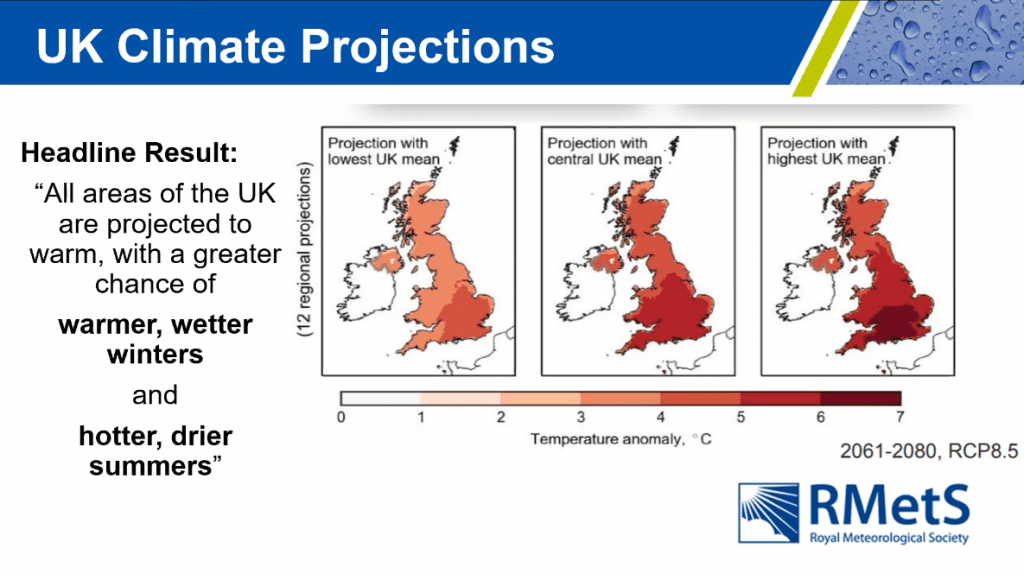

Climate change will subject the Mole catchment to additional stresses and we are seeing some already. Rainfall is projected to increase in intensity which, in our responsive clay catchment, risks flash flooding. Whilst rainfall will get more intense, more summers will be hotter and drier.

Climate change means NFM schemes are urgently needed to store more water in our catchment to combat the twin threats of drought and flooding. Such nature based solutions can also contribute to reducing water stress and protecting our vulnerable habitats from drought. It’s a win win win!

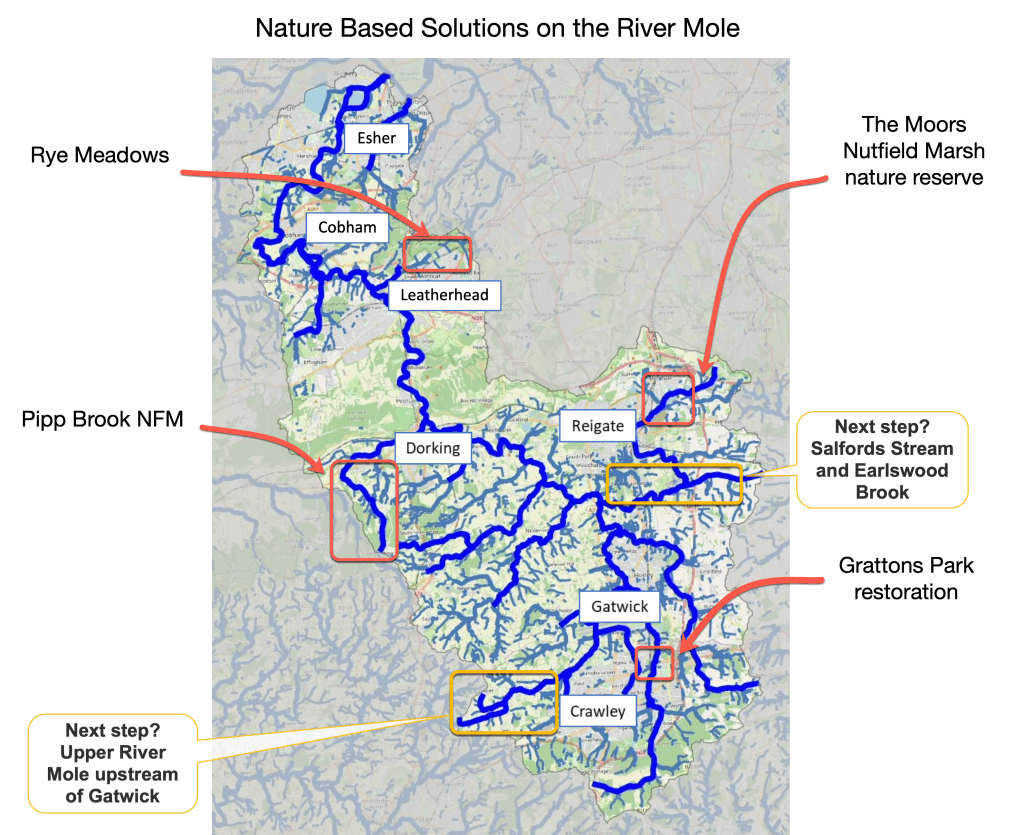

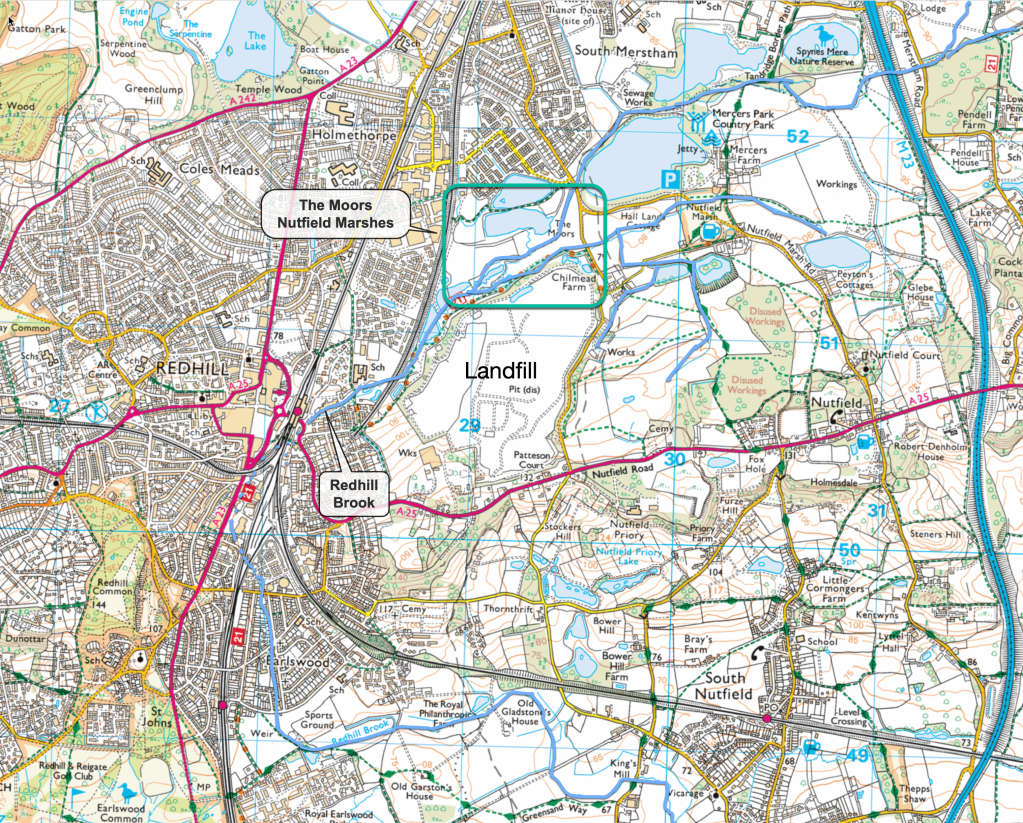

At present, as already mentioned, we only have a handful of NFM or nature based solutions in the Mole catchment. The NFM scheme on Pipp Brook is the only leaky dam project in the Mole catchment but there are three of other schemes which can be included as Nature Based Solutions. Nutfield Marshes in the Redhill Brook catchment includes a wetland nature reserve, called The Moors, which has marshland, scrapes and swales designed to store water and flood in times of high rainfall.

The Moors sits rather incongruously next to the mountainous BIFFA landfill site which rises above the marsh and wafts the smell of waste over the herds of sheep and wetland wildlife.

Whilst Nutfield Marshes was not principally designed as a flood management scheme it is nonetheless important in moderating flow into Redhill Brook just before it enters the lengthy culverted section under the town.

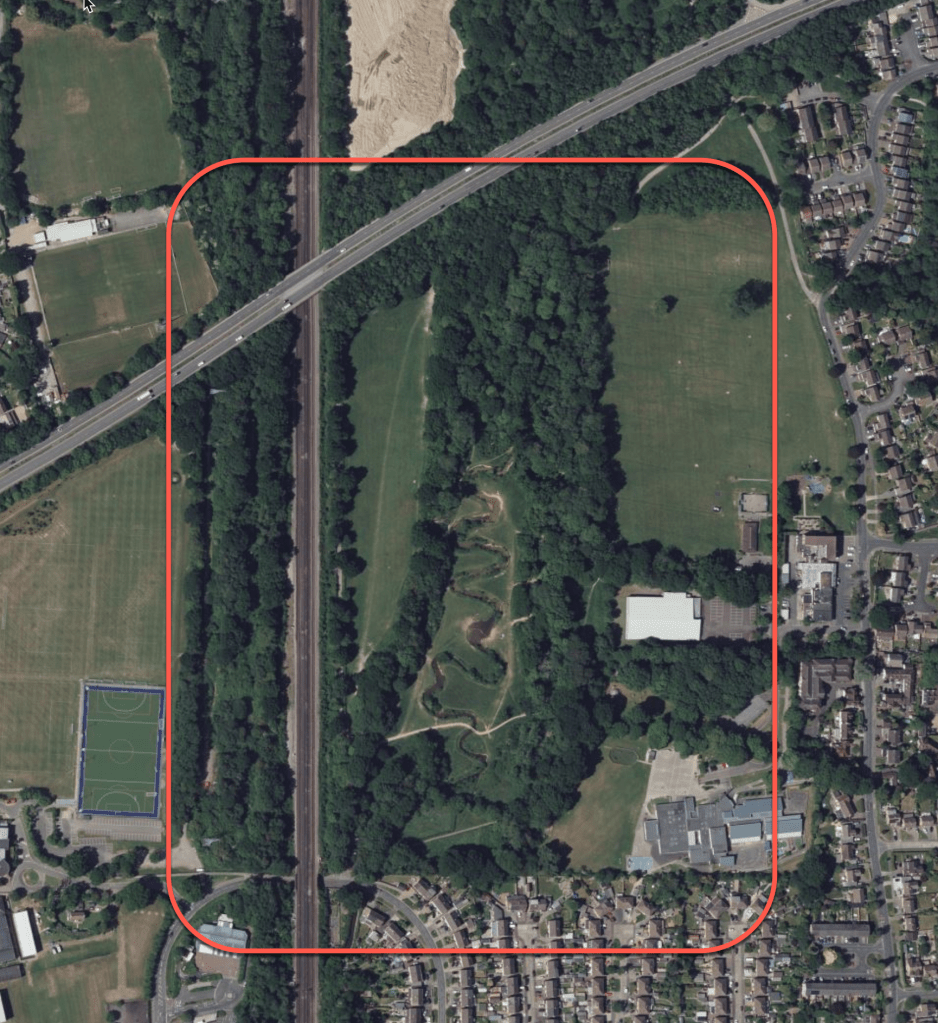

Another notable nature based solution in the Mole catchment is Grattons Park Local Nature Reserve in Crawley. This has elements of NFM.

Here, for a short stretch only, the Gatwick Stream has been reconnected to its flood plain by the creation of a series of beautifully designed meanders through a valuable green space sandwiched between the railway, a major trunk road, a superstore and residential suburbs.

The Environment Agency recreated the natural curves which lengthens the pathway and therefore lowers the gradient and slows the flow in comparison with a straight channel. The sculpted channel complete with gravelly riffles and deep pools provides spawning grounds to enhance wildlife habitat amongst the trees and reeds planted on the banks. Brown Trout and Brook Lamprey live along this stretch of revitalised river. In addition to the meanders there is a scrape (temporary pond filled in wet periods) with a well built hedge barrier. There is more about this restoration scheme in the sections below.

Finally, the third example of working with nature to restore rivers is the excellent Rye Meadows Wetlands Group. This group is delivering NFM improvements along The Rye, an important tributary of the Lower Mole near Ashtead. Working with professional contractors this volunteering group have, amongst many other activities to improve the environment, cleared stretches of the Rye Brook, widened the river and realigned the banks. One major piece of work was to create a wetland area with a new pond and several scrapes. In this way their work has improved habitat, reduced pollution and improved access to the river environment as well as potentially contribute to reducing flooding by storing more water in the landscape.

A close-up of the Pipp Brook leaky dams

Whilst the three examples above show soft management occurs elsewhere, Pipp Brook is the only purpose-built NFM scheme in the Mole Catchment and certainly the only scheme using leaky dams, a staple of Natural Flow Management and slowing the flow.

Back on the tour, Ben showed us a selection of the 30+ natural flood management elements installed on Pipp Brook. The structures included more than 30 leaky dams and the creation of several marshy wetland areas. Details about how these techniques work, and several more, are dealt with later.

Ben’s particular interest is centred on developing catchment scale modelling from calibrated and validated measurements of real world leaky dams so results can better inform effective location and design. To be successful, Natural Flood Management Schemes (NFMs) must be well designed and carefully installed. The results of Ben’s pilot will improve modelling to ensure the success of future schemes.

“The Dorking NFM project has been a unique opportunity to study the hydraulic functioning of these NFM measures (Leaky Dams), in a way in which has not been possible before. Detailed monitoring including river levels, fixed-point photography and structural surveys has given the project access to detailed data, which can then be used to validate hydraulic models used to represent these NFM structures. This gives us confidence that the model is accurately representing the reality, including the inherent leakiness through the structure. This will then assist with others wanting to complete similar projects, providing a basis for modelling and monitoring principles for NFM”.

399_13_SD07 Document template: green 1 column

Ben Tonkin, PhD student and Environment Agency employee

The aim of leaky dams is to “connect the river to its flood plain” by pushing flood water out of the channel and onto the flood plain and storing it in wetlands.

Leaky dams cause peak discharge to be reduced by delaying a considerable volume of flood water behind dams on the flood plain. The water is absorbed in marshy wetlands and slowly released after the flood peak has passed. The wetting of the flood plain also increases the resilience of the ecosystem to drought which is such an increasingly insidious threat to wildlife which has caused untold damage to native woodland habitat in the Upper Mole watershed in Worth Forest (ref Dave Bangs, Ecologist).

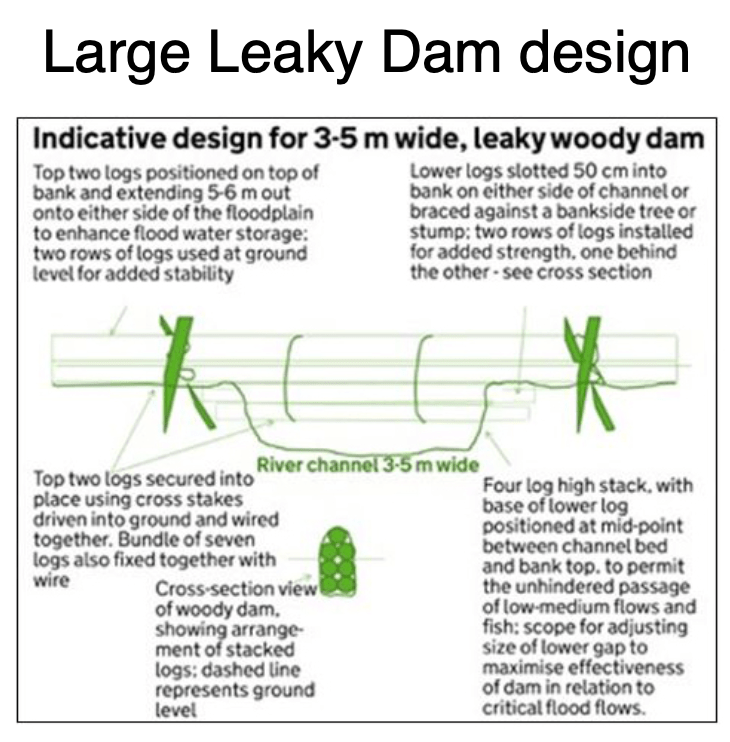

Leaky dams are not simply piles of logs haphazardly strewn across channels! Although based on naturally fallen trees, to be effective and not counterproductive to flood management or even hazardous, Ben had to ensure his dams met the current scientific thinking in modelling log dam design that ensured they performed as desired.

Log dams need to be firmly secured to the flood plain. This avoids dams being dislodged during high flow and potentially causing a hazard downstream, damage to bridges or other infrastructure, unwanted blockage or localised flooding. Leaky dams are designed to attenuate moderate flooding and not the more rare floods with recurrence intervals of 1:100 or more years. This means they must be built to withstand rare events when they could be overwhelmed. The photos above and below shows a dam on the Pipp Brook where pine logs have been firmly driven into the ground to support the embedded logs. A variety of native tree species were chosen to construct the dams to test tree type performance during the monitoring period.

There is also a risk of flow washing out the banks around the leaky dams and causing a reduction in effectiveness, increased flood plain erosion and even dam failure. To reduce the risk of washout, dams are usually built across the entire flood plain width to ensure flood water is retained and high flow does not erode new courses when pushed out of banks.

Another crucial part of the design of leaky dam design is to leave a gap under the logs. The “base-flow gap” is usually about 300mm above the winter base flow level allowing to flow to discharge unimpeded below the logs. Furthermore, the gap also allows for unobstructed fish passage, ensuring that NFMs have co-benefits for ecosystems. A biodiversity species study prior to the Pipp Brook NFM project proved the priority need for fish passage as important species such as Brown Trout, Brook Lamprey and Bullhead were found.

The base-flow gap also allows for sediment to be transported downstream. This is important to reduce the risk of silt being trapped by the dam causing sediment starvation and clear-water erosion issues downstream. In addition, a build up of sediment against dams would reduce their useful life-span by rendering them gradually less effective over time and requiring increased management and disturbance to clear unwanted deposition.

The most effective NFMs combine a series of elements downstream to act in combination, a so called pyramid design with dams increasing in size downstream. Spacing of each leaky dam was calculated on the basis of 7x the width of the channel.

How do NFMs control flooding, reduce pollution and increase drought resilience?

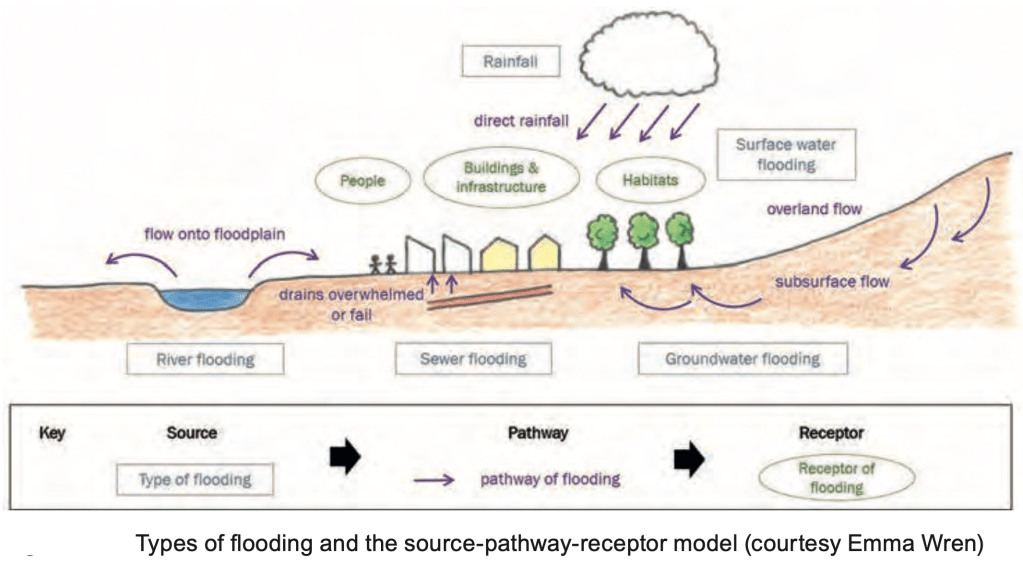

Both SuDS and NFM techniques benefit rivers, habitats and people in numerous ways by slowing runoff, storing water in the landscape and improving river quality by reducing pollution.

There are three key aims of NFMs and SuDS which can be summarised as “slowing the flow”:

- slow runoff rate: the speed with which rainfall reaches the river.

- reduce runoff volume: the amount of water reaching the river.

- reduce pollution: manage water quality and / or sediment load.

Well designed NFMs and SuDS manage both high and low rainfall intensity events which deliver different volumes of runoff and at different runoff rates. Runoff also delivers pollution to rivers.

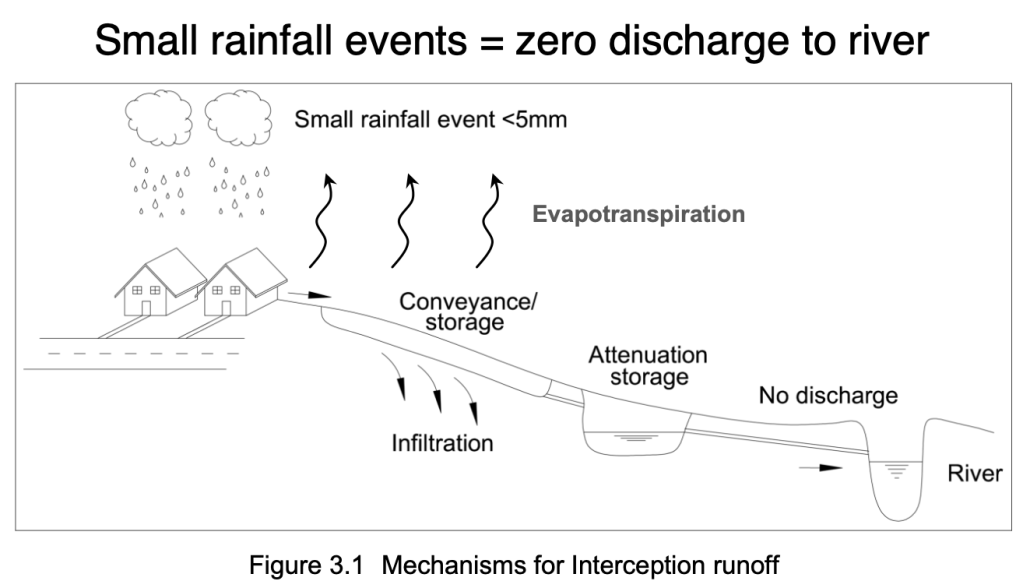

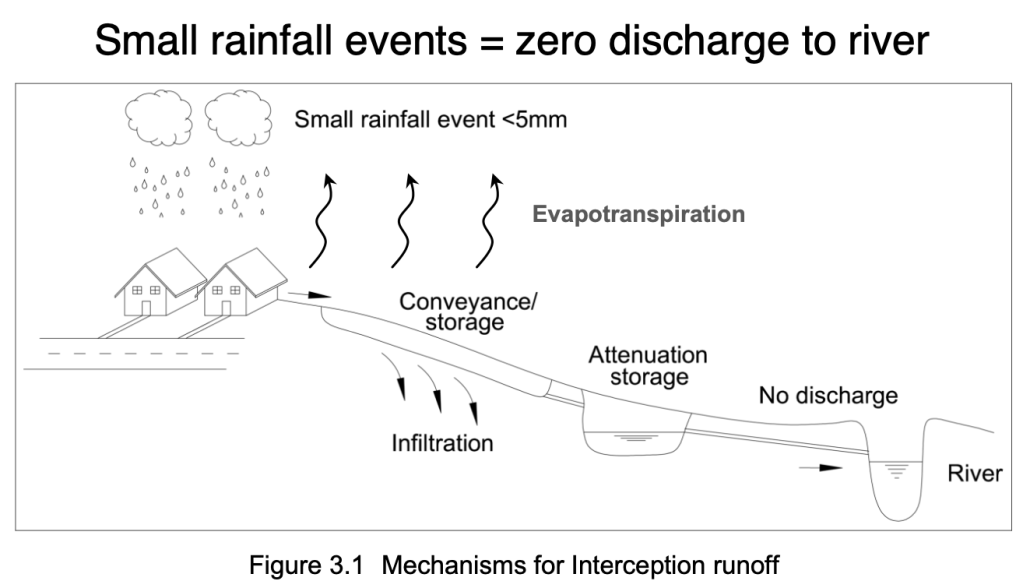

Pollution control: In natural catchments, light rainfall is intercepted by vegetation and infiltrates into soil. This means little, if any, runoff reaches the river. At least half of all rainfall is low intensity and is naturally “mopped up” in this way. However, land use change increases the cover of impermeable or less permeable surfaces leading to more rain, even light rain, reaching the river more of the time and more quickly. This creates a near-continuous stream of water into rivers even during periods of light rain. This continuous, unabated runoff also delivers polluted discharge to the river whether it’s pollution from roads, urban or industrial land use or sediment rich runoff carrying pollutants from open fields or cleared rural landscapes. NFMs and SuDS seek to abate this light rain and ensure that land use change does not cause a continuous feed of pollution from which rivers “never get a break”. Storing and filtering water through leaky dams, vegetated swales and scrapes all help to reduce runoff and so reduce pollution.

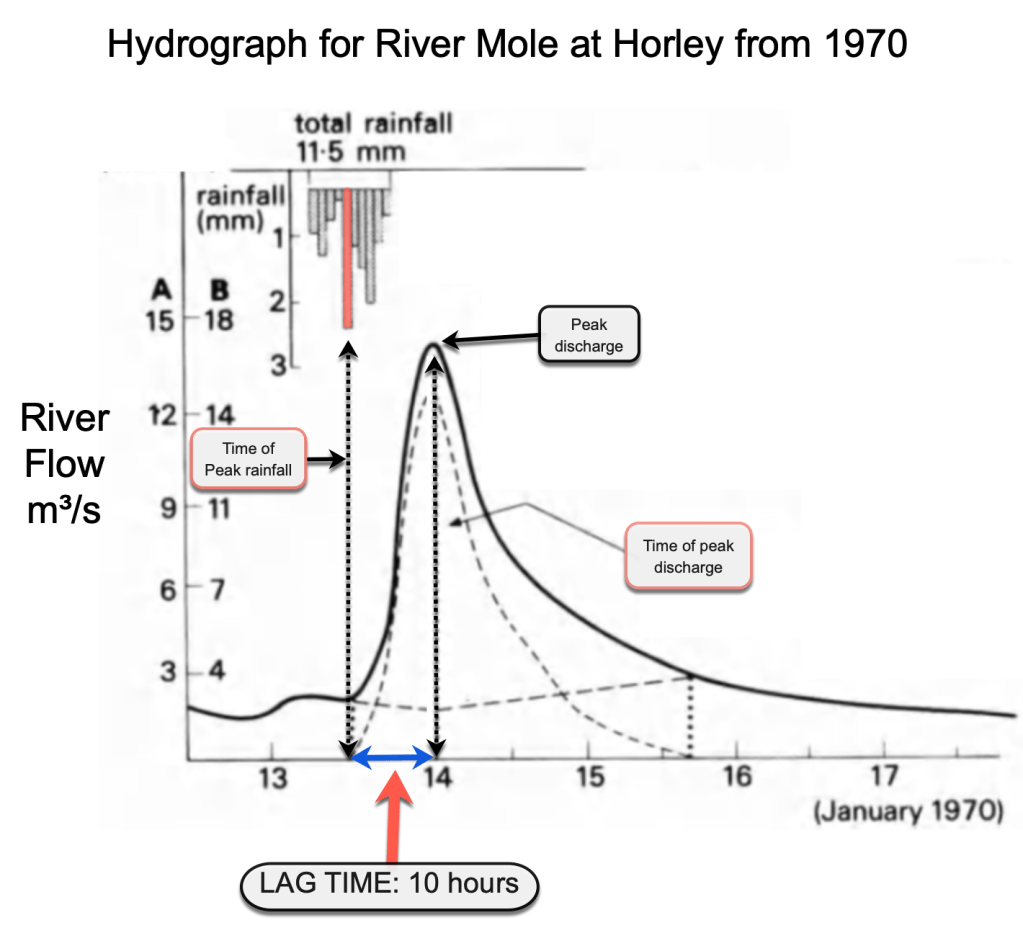

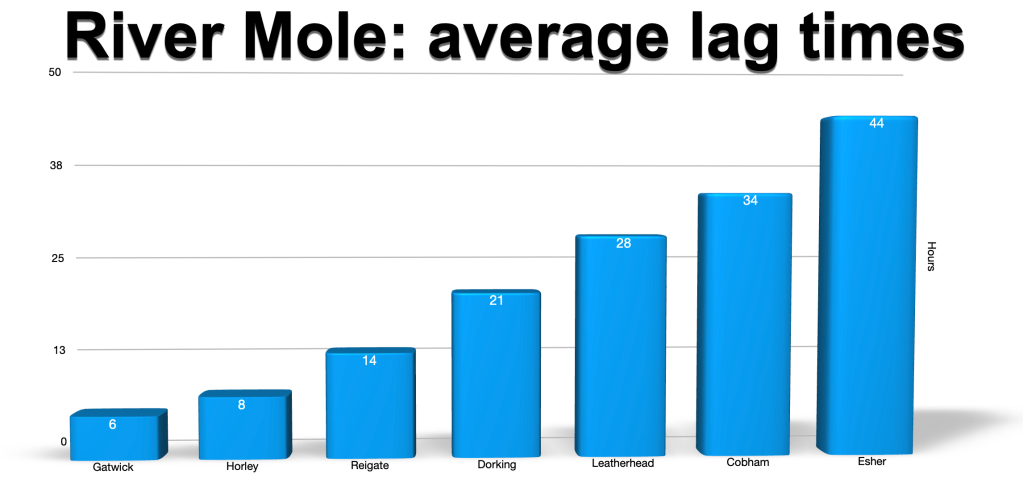

Flood control: During high rainfall events, NFMs and SuDS come into their own by storing the extra volume of runoff and attenuating flow behind leaky dams or in scrapes or similar structures. The time taken for rainfall to reach gauging stations, called the lag time, is reduced by development and land use change such as deforestation: water gets to streams quicker! Recent average lag times have been calculated for winter 2022-23 for gauging stations on the River Mole and are shown below. Notice the lag time for Horley is 8 hours compared to the 10 hours shown in the hydrograph above from 1970. This means runoff takes 2 hours less time to reach Horley than in 1970 causing more risk of flooding. This might be due to more extensive housing development during that time.

Reduced lag time causes the river to become more flashy, increasing the risk of flooding, increasing the wash-off of pollutants and increasing sediment load reaching the river and so decreasing river health and impacting river behaviour and damaging wildlife. So rate and volume of runoff is intimately linked to pollution and both of these are mitigated by NFM and SuDS.

Improving drought resilience: It is widely understood that both NFMs and SuDS are designed to reduce flooding after heavy intense rainfall. However, well designed schemes should also address river catchment behaviour at low intensity rainfall and especially in dry periods and drought.

For example, low intensity rainfall events of less than 5mm account for 50% of rainfall in UK catchments. Light rain usually contributes no measurable runoff at all in a natural catchment area because the rain is intercepted by vegetation, infiltrates into healthy soils or evaporates before reaching water courses. Infiltration augments soil water storage and increases the resilience of the catchment to drought.

After development or deforestation, runoff can occur after virtually every rainfall event. This means that streams can receive polluted or sediment laden wash-off from exposed surfaces from almost every rainfall event. Pollutants washed into rivers include sediments, hydrocarbons, suspended solids and metals. In this way, development and land use change means that rivers are constantly fed polluted and sediment rich runoff, with no breaks for recovery. It also means unabated flow is lost from the catchment, reducing resilience to drought.

Well designed NFMs and SuDS can seek to reduce this near-continuous runoff of pollution from even low rainfall events into rivers and improve aquatic ecosystem health. Furthermore, the attenuation of water in a “spongified landscape” increases the resilience of basins to drought, more slowly releasing stored water into rivers.

Drought is an insidious and serious threat to wildlife. The repeated drying out of water courses and springs in watershed habitats is hugely damaging to wildlife. Well designed NFMs can improve the storage of water and slow the desiccation of landscapes during droughts that are likely to become more frequent and hotter as climate changes.

In summary, well designed NFMs can directly reduce flooding by:

- Reducing the volume of water reaching rivers by increasing interception, infiltration and evapotranspiration by planting trees and increasing vegetation cover.

- Slowing the rate of runoff and flow by lengthening pathways, recreating meanders and adding obstructions and barriers to flow.

- Storing water in attenuation features but which include rapid emptying before the next storm arrives to maximise available storage.

- Holding back sediment to reduce soil erosion from fields and loss by outwash into rivers.

NFM can also have co-benefits such as:

- Enhancing biodiversity by creating wildlife corridors, improving habitat resilience, removing invasive species and enhancing ecological resilience. NFMs are likely to achieve biodiversity net gain so can attract partners and further funding opportunities.

- Improving soils by reducing erosion and sediment transport by rivers.

- Improving water quality through increased infiltration and wetland storage and improving flows during drought.

- Increasing carbon storage through wetland creation, peat storage or tree planting.

- Improving landscapes for recreation, tourism and local communities by increasing inclusive public access through NFM schemes.

- Increasing the resilience of catchments to droughts and thereby reducing biodiversity loss.

What makes a successful NFM?

Get behind the idea! The idea of SuDS and NFMs is to work with nature to reduce flood risk but also improve the wider health of rivers, increase the resilience of catchments to drought and reduce pollution. NFM enhances processes that naturally slow down runoff and store water in the landscape. Techniques to achieve this include the development of healthy soils, growing well managed woodland or allowing streams to meander and spill onto their flood plain.

Vary the techniques! Designing a variety of techniques appropriate for the sub-catchment is important to achieve success. For example, installing a variety of leaky log dams at intervals downstream with space on the flood plain to allow wetland formation and storage is usually more successful than installing a single leaky dam.

Work with everyone! Another key to NFM success is working with others. There are numerous groups to work with that improve the chances of success e.g local communities, land owners and farmers with local flood knowledge. In addition, important connections can be made with River and Wildlife Trusts, schools, water companies and community groups. Dialogue with land owners and farmers is key because they might be skeptical of the costs and time involved compared to the benefits. In addition, liability and ongoing asset maintenance were issues many pilot schemes reported as being most difficult to overcome when seeking landowner permission.

Go global! Importantly, NFM should be part of wider holistic strategy across entire catchments. NFM provides a catchment based approach by reducing flood risk across the catchment close to the source while supplementing traditional flood risk solutions in flood risk zones.

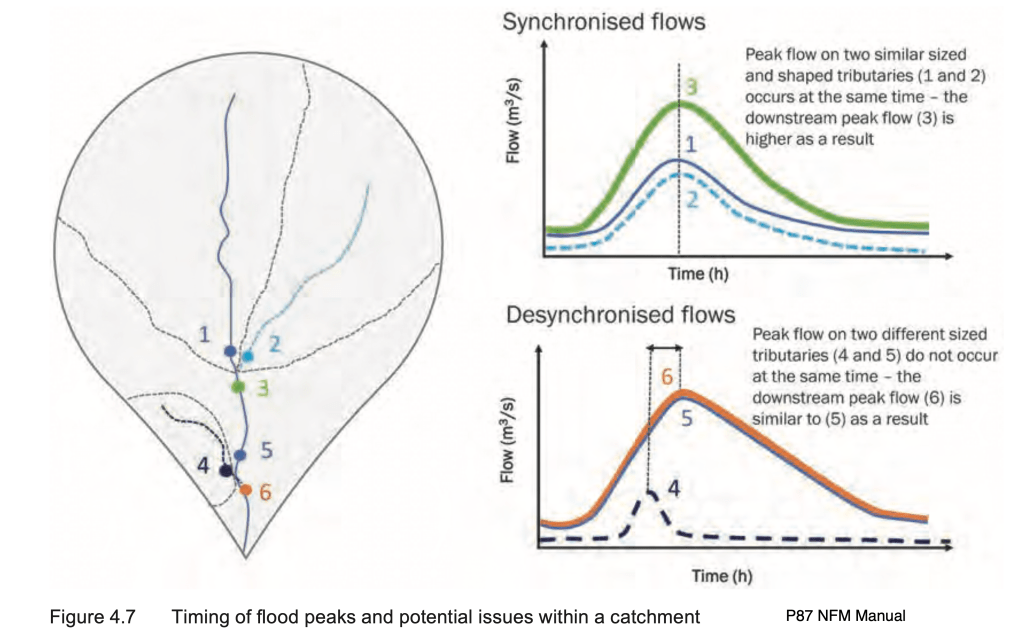

Desynchronise your flood peaks! Flood peaks travel downstream from tributaries and meet the main river at a confluence.

The figure below (from NFM Manual p87 Ciria 2022) the flood peak at location 3 receives flood peaks from streams 1 and 2 at the same time. Flood peaks are said to be “synchronised”. Synchronisation means flood peaks will be higher and flooding worse. There is a risk that flood peaks from NFM sub-catchments are slowed so they may synchronise with flood peaks at confluences with channels draining other parts of the catchment. This would increase the flood peak and make flooding worse downstream. This is called synchronisation and all flood management, regardless of whether it is natural or traditional hard engineering, should avoid increasing peak discharge. Local knowledge combined with hydrological expertise is required to design a desynchronised natural flood management system.

Natural Flood Management: a menu of techniques for the Mole catchment

A successful and effective NFM requires an understanding of the causes of flooding and hydrological processes in the whole river catchment as well as details about the menu of possible methods which are outlined in this section.

NFM requires engagement with land owners and communities to move forward with agreed plans and clarity on liabilities and responsibilities in the longer term, which can be sticky issues! Furthermore, an estimate of costs (e.g installation, loss of land/farming, construction, maintenance etc) and benefits (e.g reduced flood risk benefits and co-benefits) are required to guide decision making.

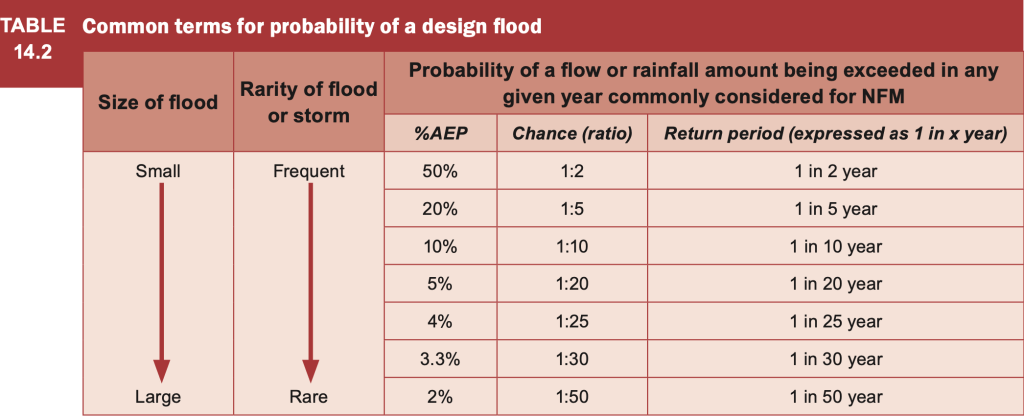

The key aim of NFM is to reduce flooding, so let’s review how we talk about flood risk.

A common way of expressing flood risk is to use Annual Exceedence Probability (AEP). AEP is expressed as the % probability of a flow being equalled or exceeded. Smaller floods occur more frequently and so the annual chance of exceeding these flows is high e.g a 100% AEP would occur every year. Large floods occur rarely and so the annual chance of these flows being equalled or exceeded is very low e.g a 0.01% AEP is a 1 in 1000 year flood. The 1968 flood on the Mole was a 1:200 year event or 0.5% AEP.

The AEP is an accurate way of considering flood risk for a catchment or river.

- 50% AEP has a return period of 1 in 2 years. These are small, frequent flood events.

- 2% AEP has a return period of 1 in 50 years. Typically, this is the maximum design flood for NFMs.

- 1% AEP has a return period of 1 in 100 years. Typically, this is the design flood for larger flood alleviation schemes. e.g. UMFAS

- 0.5% AEP has a return period of 1 in 200 years. These are large, rare flood events.

- 0.1% AEP has a return period of 1 in 1000 years.

NFMs are small scale projects designed to address more frequent flood events that occur every few years (50% AEP) to every 50 years (2% AEP). In larger, less frequent 1 in 100 (1%) to 1 in 1000 year (0.1%) floods, NFMs would be overwhelmed. Flood protection for these extreme but rare events is usually catered for in larger traditional flood alleviation schemes.

NFM measures are small-scale and typically aim to modify flows during flood events that have a 50% to 2% chance of being equalled or exceeded each year. i.e. return periods of 1 in 2 years and 1 in 50 years respectively.

Natural Flood Management Manual CIRIA C802 p178

What follows is an outline of the main natural flood management techniques, including some benefits and some costs. This section was sourced from the Natural Flood Management Manual by Cirio.

1.Land management

Changing farm and land management can sustain good soil health and reduce flooding by soils slowing and storing more water. Healthy soils encourage infiltration. Techniques to improve land management techniques include:

- Crops: Changing crop types or sowing cover crops to increase organic matter, contour ploughing across the slope, minimum or no tillage. All of these techniques can store more water, reduce erosion and run off and enhance soil health.

- Grazing: reduce stock density or move herds to mob-graze new areas and reduce localised erosion

- Vehicles: reducing compaction by changing types of tyre, lower inflation, avoid use of vehicles in wet conditions, move gates to drier areas.

- Reduce compaction: mechanically spiking soils to improve aeration

- Encourage natural habitats: eg wetlands soak up water and release it slowly into rivers and restore habitats that enhance soils.

- Improving land and soil management can significantly reduce diffuse pollution from farmland.

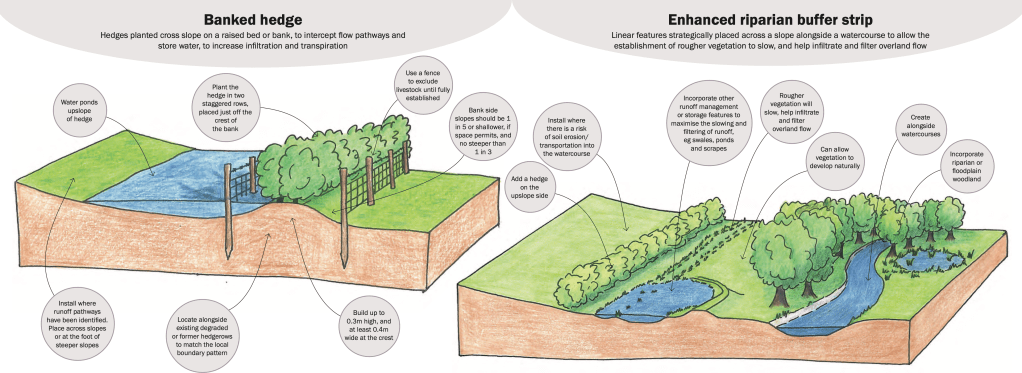

2.Runoff Management

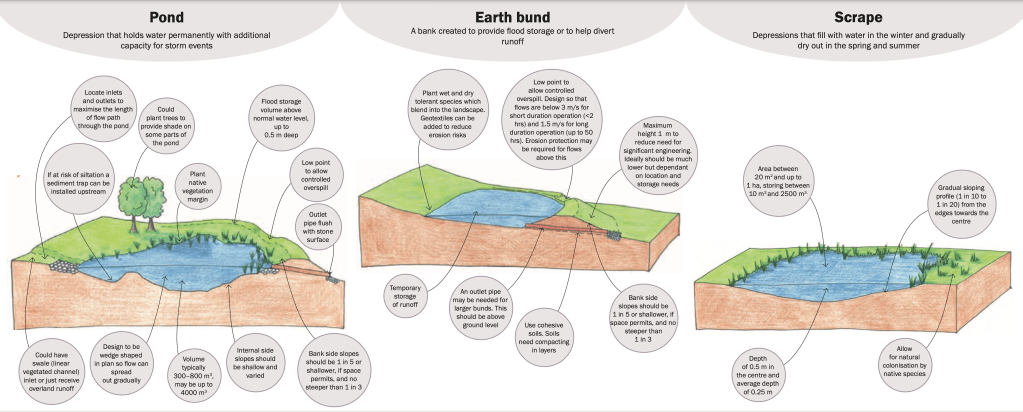

Managing runoff includes techniques to interrupt, slow, store or divert flow to delay it from reaching the river. All of these techniques also improve water quality by trapping sediment and pollutants.

- Ponds: permanent water holding features usually in low points of fields built with additional capacity for storms. Releasing excess water in a controlled manner over a low point along safe pathways.

- Scrapes: depressions which fill up in winter but are usually dry in summer. They are temporary ponds.

- Swales: shallow linear vegetated channels to transfer runoff slowly after rain and, where possible, allow infiltration into permeable soils. Vegetated swales in sunny locations to promote growth can effectively attenuate runoff and filter pollutants. Check dams can slow the flow further and also trap sediment which improves water quality.

- Bunds: usually earth banks built across slopes to intercept runoff and store it.

- Buffer strips: strips of land, often adjacent to rivers, removed from direct management to allow natural vegetation to grow helping infiltration and filtering of overland flow. They also reduce erosion and act as wildlife corridors. Defra require strips of at least 5 m width.

- Cross-slope hedges and trees: native hedgerows of at least 1.5m width provide great biodiversity and wildlife corridors. They increase interception and infiltration and take up water. Hedges can reduce spread of disease to livestock by reducing animal contact. Hedges also improve water quality and capture and store carbon.

- Cross-drains: farm tracks can act as water course. Cross-drains will divert runoff away from tracks reducing flooding, runoff and erosion.

The location and design of these management techniques is important to achieve success. For example, if ponds are too deep they may become anoxic or stagnant, while those built too shallow may suffer from algal blooms. Runoff into ponds from tracks or buildings may also impact the health and ultimate success of water storage techniques.

Runoff storage techniques require maintenance. For example, land owners will need to periodically remove sediment that has accumulated in swales, scrapes or ponds or behind check dams. The sediment can be returned to fields. Blockages may also occur in pipes or culverts or outlets especially after storms. Overgrowing vegetation will need to be mown or cut regularly to maintain effectiveness of storage. Damage to structures can occur and invasive species may also need to be removed.

3. Catchment Woodland

Trees intercept rainfall, increase evapotranspiration, uptake soil water and slow down runoff downslope. Furthermore, woodland filters water and improves water quality at the same time as capturing and storing carbon. Woodland has numerous co-benefits such as attracting wildlife, increasing biodiversity, providing shelter for livestock and additional revenue from wood products as well as providing benefits to people from recreational visits. There are many benefits to trees!

Trees are most effective at reducing runoff when grown in these strategic locations:

- Across slopes: blocks of woodland across slopes interrupt surface flow of water encouraging infiltration into soil and improving water quality.

- Adjacent to rivers: riparian woodland strips along river banks slow the flow and, in time, large woody debris falls into water courses further slowing the flow.

- On flood plains: increasing roughness slows the flow during floods, increasing water storage and delaying flood peaks downstream.

- Across a catchment as a whole: regions with flashy impermeable soils benefit from tree cover.

Trees often require planning consent before planting or changes in woodland cover can be started.

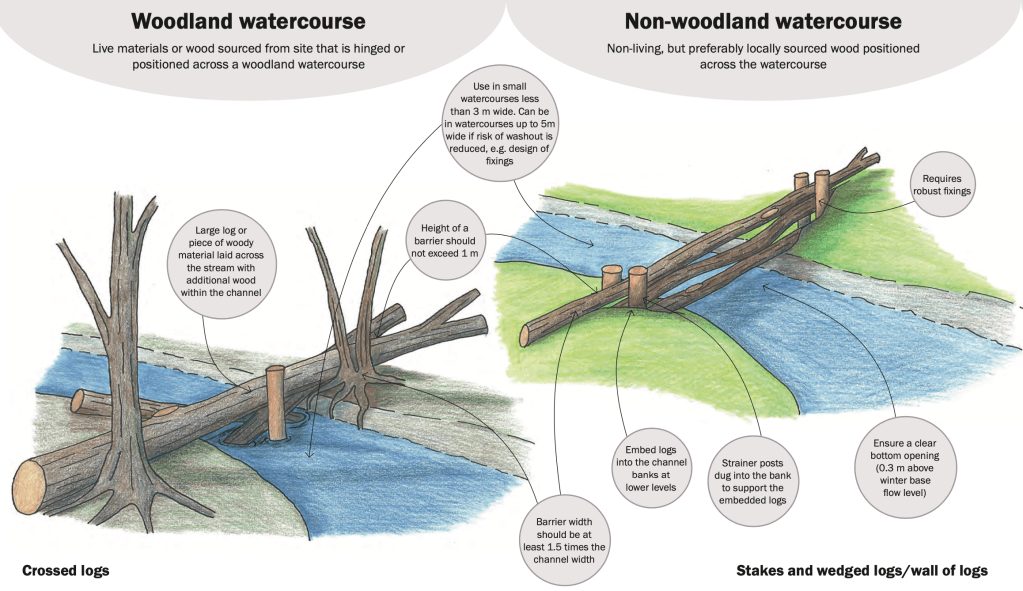

4. Leaky barriers

Leaky barriers or leaky dams are usually wooden barriers installed across water courses and flood plains which intercept river flow, push water onto the flood plain, increasing attenuation storage and slowing the flow. Downstream flood risk can be reduced.

They are usually installed in woodland but can also be built in gullies and streams in open country. They are most effective when designed as a series of barriers at defined intervals downstream. Whilst it’s too early for results from the Pipp Brook leaky dam scheme, a similar NFM in Pickering, North Yorkshire, found the flood risk was reduced by approximately 15-20%.

Benefits and some problems of leaky barriers include:

- Flood risk reduction: flow can be attenuated and reduced but trapped water may increase localised flooding upstream if not carefully positioned. Leaky barriers may also become dislodged and wash downstream blocking bridges and culverts causing flooding.

- Environmental improvement: leaky barriers trap silt and improve water quality, regulating temperature and water level. However, lower sediment load downstream can cause clear-water accelerated erosion.

- Habitat creation: increased wet land areas can improve food sources and shelter for wildlife and regenerate habitats. However, fish or eel passage may be interrupted and may be stranded in subsiding water without careful design. A gap beneath barriers is essential.

- Drought resilience: retention of water during droughts can improve habitat resilience in prolonged dry periods.

- Pollution reduction: Studies have shown that log jams reduce phosphate concentration by 3.6mg/l and Nitrate was also reduced.

There are technical recommendations as to the best designs and locations for leaky barriers. For example, spacing barriers in series should be 7-10 channel widths downstream to encourage channel stabilisation. Furthermore, leaky log dams should extend across the entire flood plain to ensure there’s less risk of washout and erosion undermining the banks around the barrier. Avoiding locations upstream of structures like bridges and culverts reduces the risk of damage and flooding should the barriers become dislodged.

Restraining barriers so that they do not become dislodged in floods is also very important. Recommendations for barrier restraint includes the use of living materials such as partly fallen trees with a hinge allowing them to continue to grow across the water course whilst being restrained from being dislodged downstream in floods. Restraining using natural features such as gaps between bedrock outcrops or standing trees are reliable. Embedding into flood plains can also be effective particularly where stakes are driven into deposits. Use of native wood will encourage habitat biodiversity.

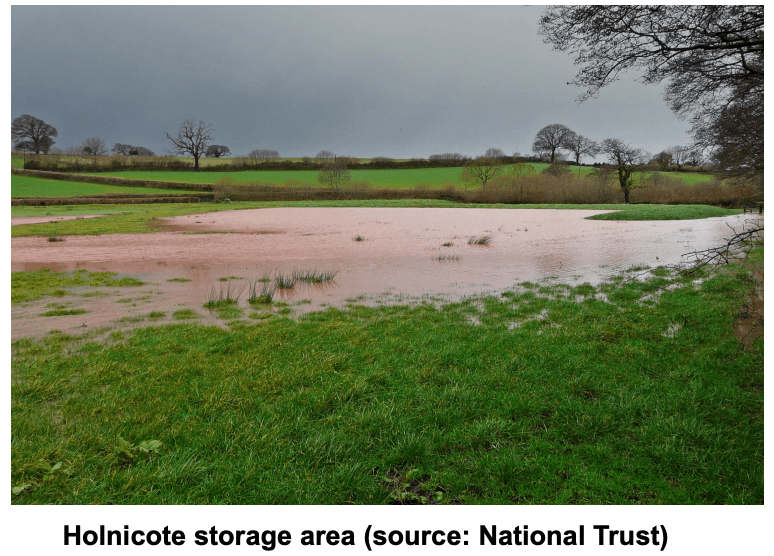

5. Offline storage

Increasing temporary water stores on flood plains can reduce flood peaks. Offline storage areas can be built or adapted to contain water, store it and then release it in a controlled way after the peak flow has passed. Techniques include scrapes, ponds or earth bunds to trap water on the flood plain.

Small temporarily filled ponds called scrapes are designed to attenuate or delay flood peaks until the peak volume has passed. They are engineered bowl shaped depressions trapped by a bund or excavated into the contour of a slope. They usually have an inlet from the river channel such as a leaky barrier or flow control structure that allows water to flow into the pond at peak levels and infiltrate naturally into the ground or drain out slowly as levels subside.

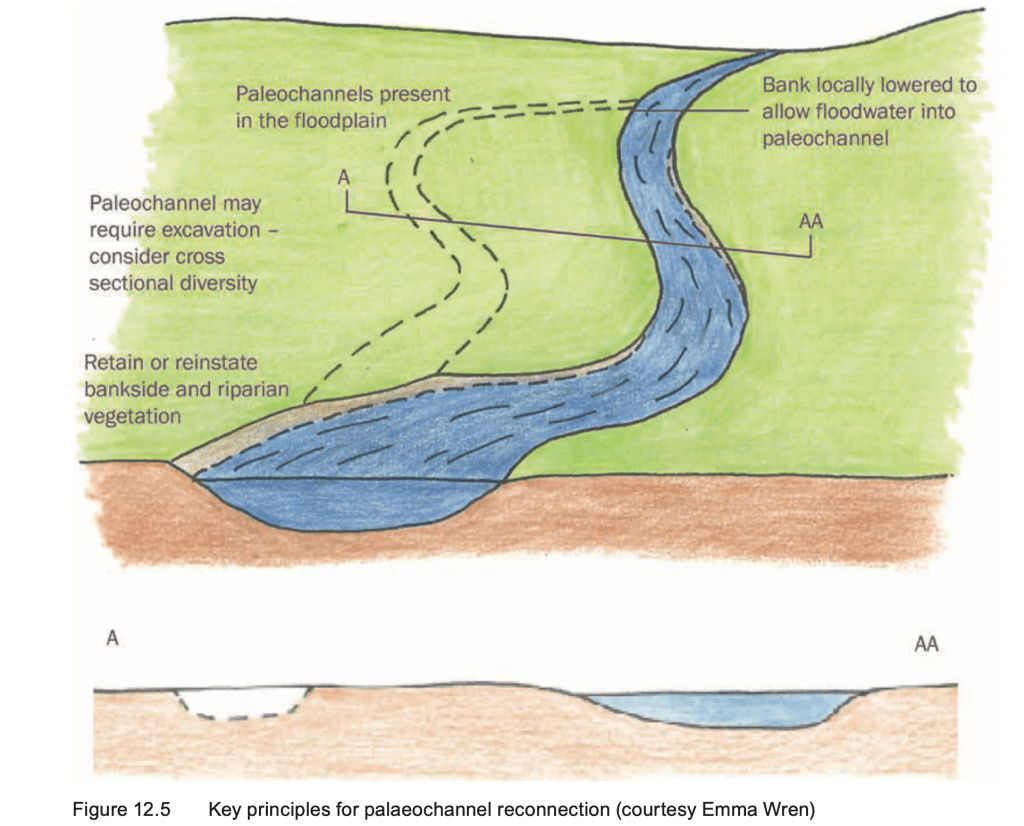

6. Flood plain reconnection and restoration

To accommodate urban and industrial development, over the years rivers have been straightened, realigned and engineered with concrete bed and banks with countless weirs and other flow control structures. This has impacted river health, not least interrupting fish passage.

Restoring the flood plain involves removing or lowering artificial embankments (levees) and other traditional flood defences that prevent rivers from connecting with the flood plain.

Reconnecting the river to former courses, called “paleao-channels” or engineering new ones creates channels, washlands and wet lands that will store water and reduce flooding downstream.

There are numerous benefits from reconnecting rivers to their flood plain.

- Water, sediment and nutrients are carried onto the flood plain improving habitat and supporting wider ecosystem recovery including the creation of wetlands, a threatened habitat. Freshwater wetlands have been valued at £1300 per ha per year (2008 prices).

- Well designed wetlands can improve local recreation amenity with boardwalks encouraging a link between communities and the natural environment e.g creating an extra 50ha of floodplain (Norfolk Broads) £27m of recreational value over 100 years.

- Accompanying wetland restoration will often include tree planting in the flood plain which captures and stores carbon. e.g 1ha of restored floodplain provides £52 per tonne of carbon sequestration benefits.

- Improve drought resilience by storing water in the soils and wetlands on the flood plain. This can also recharge groundwater in connected aquifers.

- Reduce erosion by diverting water out of the channel so that it disperses onto the flood plain.

- Improved soil health with regular inundation and deposition of silt to form alluvial soils.

There are also some risks to mitigate including the spreading invasive species into the flood plain, stranding of fish in depression storage on the flood plain as floods subside and increasing flood risk locally.

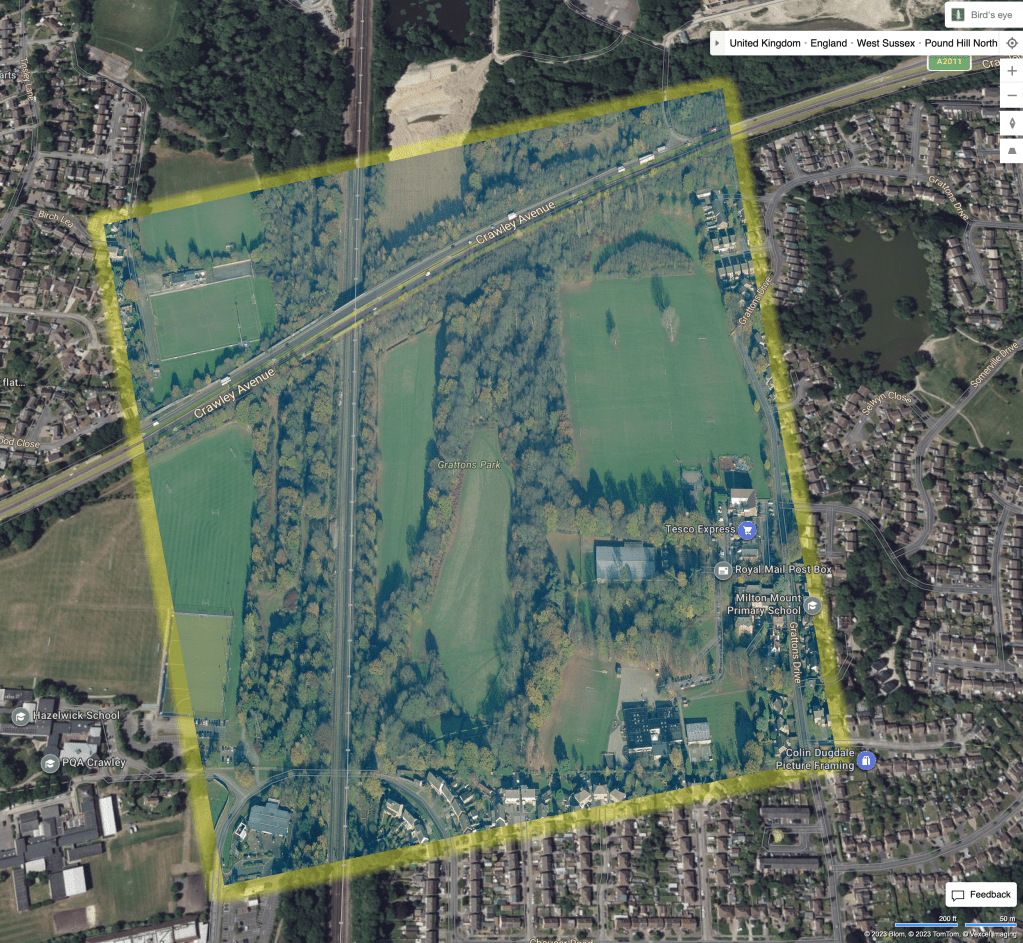

Grattons Park: an example of river restoration in the Mole Catchment

An example of river restoration is found on the River Mole at Gratton’s Park in Crawley. This small location saw the recreation of a natural river channel shape both in plan and profile through the reintroduction of meanders across the flood plain, replanting along banks and construction of scrapes to attenuate flow.

Grattons Park is a green open space sandwiched between a railway, a major road and residential development of Crawley. A series of meanders has been recreated along a short stretch of the Gatwick Stream in Crawley.

The Environment Agency along with English Nature designed the river to emulate a natural course and “reconnect” the river to it’s flood plain. This included not only engineering sweeping curves but also creating natural features such as riffles, pools and a scrape.

Restoring the natural channel shape such as meanders, slows the flow by adding length and connects more of the river to it’s flood plain creating storage, reinstating wetlands and improving habitats. Channel restoration might also include removing barriers to flow such as weirs or constraining structures such as artificial banks all of which allow the river to spread out, naturally deposit and move sediment across the channel bed and build natural geomorphological features.

Furthermore, Grattons Park shows the importance of improving the recreational amenity of a place by restoring and improving river habitats. The bridges and variety of paths in Grattons Parkmakes it a popular open space for urban residents.

Unfortunately, at just over 600m in length, the improvements at Grattons Park are a modest scale and the stresses on the river are returned to all too quickly on leaving the park where it is culverted under the formidable A2011. Before and after entering the culvert a cocktail of toxic road runoff discharges unimpeded into the stream via roadside ditches that collect runoff from the A2011.

And finally…where next for NFMs on the Mole?

There is great potential for more nature based solutions in the Mole catchment. Earlswood Brook and Salfords Stream are both prime candidates for NFM consideration. They have rural or semi-rural catchments with farmland and wooded sections that offer plenty of potential for NFM treatment. They are also of a size that could show measurable change as a result of NFM installation.

The Upper Mole is also a prime candidate. Lag times are short prior to reaching urban areas vulnerable to flooding including Gatwick, an international airport sitting on the flood plain! This sub-catchment is also under threat from significant housing development so an NFM could attract funding from developers seeing options for Biodiversity Net Gain.

While Gatwick Stream, which carries some 50% of the discharge of the Mole at Horley, now benefits from the Upper Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme, the River Mole itself, upstream from Gatwick, has no flood protection at all. This tributary was partly responsible for the flood impact on the airport on Christmas Eve 2013. The River Mole itself would therefore benefit from NFM treatment as it has a short lag time of only 6 hours to the gauge at Gatwick. At present it flows through rural countryside ideal for an NFM scheme. I say at present because there is a planning application for a huge housing development of 10000 homes to be built across the flood plain!

I hope you enjoyed this post on Natural Flood Management in the River Mole catchment. Please leave a comment and hit the “like” button if you appreciated the article. Many thanks!

References

tonkin, B.: Nature-based solutions for flood mitigation:Monitoring and modelling leaky barriers. A case study from the South East of England. , EGU General Assembly 2023, Vienna, Austria, 24–28 Apr 2023, EGU23-7126, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu23-7126, 2023.

Working with natural processes to reduce flood risk [WWW Document], n.d. . GOV.UK. URL https://www.gov.uk/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-research-reports/working-with-natural-processes-to-reduce-flood-risk (accessed 4.10.23).

CaBA Flood Working Group & National Flood Forum https://nfm-theriverstrust.hub.arcgis.com/pages/national-flood-forum

Natural Flood Management Programme: evaluation report [WWW Document], n.d. . GOV.UK. URL https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/natural-flood-management-programme-evaluation-report/natural-flood-management-programme-evaluation-report (accessed 4.11.23).

Applicant’s guide: Capital Grants 2023 [WWW Document], n.d. . GOV.UK. URL https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/capital-grants-2023-countryside-stewardship/applicants-guide-capital-grants-2023 (accessed 4.11.23).

Flood and coastal erosion risk management: policy statement [WWW Document], 2020. . GOV.UK. URL https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/flood-and-coastal-erosion-risk-management-policy-statement (accessed 4.11.23).

Flooding by design – Mott MacDonald [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.mottmac.com/views/flooding-by-design (accessed 4.12.23).

Natural Flood Management Manual, CIRIA: Wren, E, Barnes, M, Janes, M, Kitchen, A, Nutt, N, Patterson, C, Piggott, M, Robins, J, Ross, M, Simons, C, Taylor, M, Timbrell, S, Turner, D, Down, P (2022) The Natural Flood Management Manual, CIRIA, London, ISBN: 978-0-86017-945-0

Rye Meadows Wetlands | Rye Meadows [WWW Document], n.d. URL https://www.ryemeadows.org.uk/ (accessed 4.26.23).

A list of Pilot NFM schemes in England

Leave a comment