This is Part 3 of the epic story of the formation of the River Mole catchment and the Weald. It’s a challenge piecing together the key events of the Tertiary relating to the Mole landscape. This post has become a discussion weighing up different theories and following threads of evidence from various articles and references. I hope you enjoy the story!

Part 1 is here: https://themolestory.com/2023/01/31/making-mole-hills-out-of-mountains-the-formation-of-the-mole-and-the-weald/

Part 2 is here: https://themolestory.com/2023/02/21/making-mole-hills-out-of-mountains-part-2-the-mesozoic-trough/

What happened in the Tertiary, stayed in the Tertiary!

The Tertiary period started 66 Million years ago and ended with the onset of the “Ice Age”, the Pleistocene, 2.6 million years ago. The immense 63 million year time span takes us from the end of the dinosaurs, basking in a greenhouse climate, to the eve of human beings evolving in a much colder world. During this time, extraordinary Earth forming events contributed to dramatic global changes in climate and life. Whole mountain ranges and oceans across the World came and went. Meanwhile, the fabric of our own local landscape was formed.

However, my feeling is that, whatever happened to the Weald in the Tertiary, stayed in the Tertiary! What I mean by this is that, while the importance of Mesozoic rocks are clear to see and geological events in that period are well documented, the evidence of what happened to the Weald during the Tertiary is opaque and much harder to piece together as a clear story. Ironically, the story of the ancient Mesozoic is arguably less of a mystery than the more recent Tertiary. Nevertheless, let’s have a go and dive into the goings on in the Weald through the Tertiary !

Looking through the Mole Gap, darkly… is it possible to imagine the mysterious imprint of the Tertiary on our landscape?

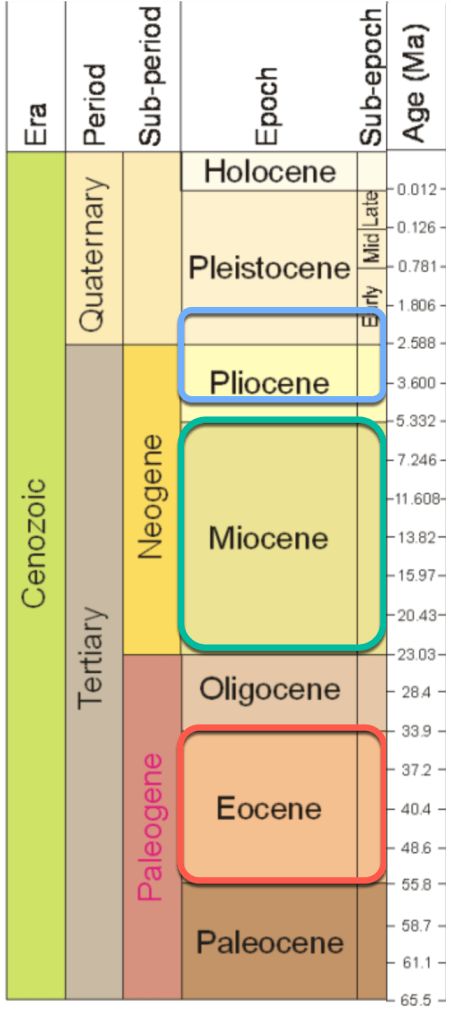

Let’s start with what we know. The Tertiary is split into two sub-periods, the Palaeogene and Neogene, which are further divided into five epochs. The term Tertiary is a little old fashioned but I’ll use it here as it is familiar and makes sense preceding the next big period, the Quaternary. All five Tertiary epochs have, at one time or other, laid claim to be the decisive moment in Weald formation!

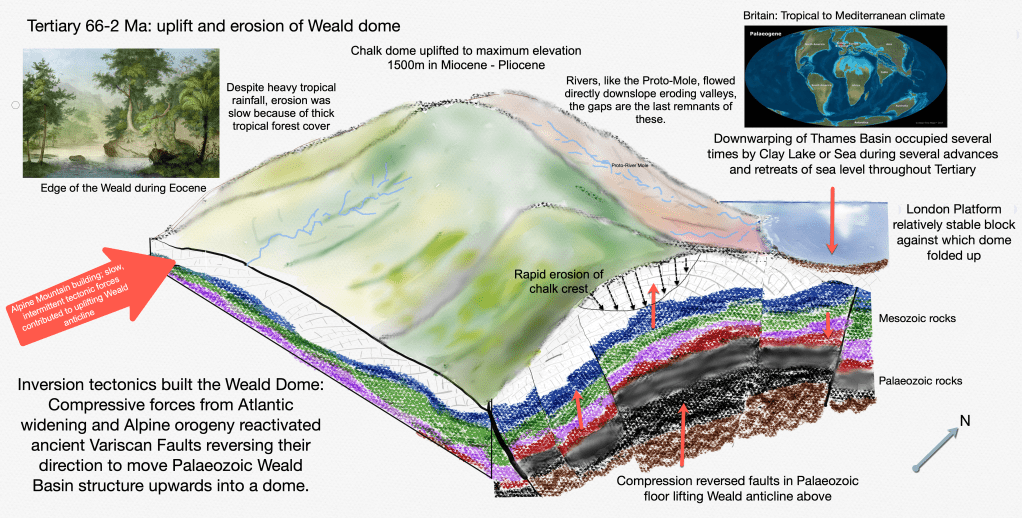

Without doubt the Tertiary was the main period of “construction” of the Weald but putting together what happened when is challenging. The traditional theory is that, part way through the Tertiary, a great uplift of land forced the rocks of the Mesozoic Weald basin into a giant dome. The summit of the dome eroded most quickly and may have looked a bit like the chalk mountains of Kazakhstan today but you’ll need to imagine dense vegetation covering the hills to fit the tropical Tertiary Weald accurately.

The usual story of Weald Formation explains the uplift was due to the collision of Africa and European plates causing the layers of rocks in the Weald Basin to fold up into a giant dome. The dome theory, while not entirely abandoned, has had to be adapted in the light of new evidence so that one single episode of uplift is now considered unlikely.

New evidence includes, for example, research that shows tectonic earth moving forces affecting the Weald were not restricted to one episode but occurred throughout the Tertiary and included extensional forces from Atlantic Ocean spreading as well as compressive Alpine tectonic forcing later on. In addition, the existence of overlying patchy “marine” Tertiary deposits overlying, unconformably, the Chalk downs complicates the chronology of one single uplift and there’s little evidence at any time of a dome structure emerging as an island surrounded by a Tertiary Clay Sea (D.K.C.Jones). So one big Wealden anticline seems unlikely.

Furthermore, deep borings and seismic surveys conducted in the Weald by the hydrocarbon industry have lit up new discoveries from as deep as the Palaeozoic Floor suggesting that the underlying basin structures, including those Variscan faults mentioned in previous posts, had a lot more control over our landscape formation than previously known.

So, perhaps regrettably, there is less likely to have been a single “key moment” of uplift for the Weald resulting in one enormous dome like mountain rearing above Brockham, Dorking or Reigate! More likely is a series of earth movements occurring throughout the Tertiary which raised a Weald land surface more modestly above the waves, only then to be weathered and eroded each time and, on occasions, submerged beneath the sea again. These cycles repeatedly and progressively “exhumed” the bones of a landscape mainly by rivers picking away at less resistant rocks (eg clay) while leaving more resistant rocks (eg chalk) as higher ground.

I’d summarise Tertiary events thus: the Weald landscape has been repeatedly “raised, eaten and rinsed” over the 60 million years of the Tertiary, each time producing somewhat similar arrangements of hills from the same geological cake each time. So no single mighty dome as such but a series of eroded mini-domes perhaps?! But this is a personal theory based on unpicking articles. The single raising of a one dome is still valid and I’ll be referring to it throughout.

When exactly each phase of uplift, denudation and inundation occurred is not crystal clear. Indeed, every epoch during the Tertiary seems to have a good claim to “that” critically important earth movement moment that gave shape to our modest lumpy landscape.

To clear the fog, here’s a summary of important earth forming events in the Weald that took place in each of the five Tertiary Epochs. We’ll go into more detail and tie up loose ends later in this post so please excuse any apparent repetition.

Paleocene: 65-55Ma: some accounts argue that uplift kicked off straightaway in the Tertiary and probably coincided with the regression of the Late Cretaceous Chalk Sea. This early uplift would have raised a largely “intact” chalk landscape above the waves for the first time, allowing 30 million years for weathering and erosion to “unroof” the Chalk over the highest land. Unroofing or denuding of that first appearance of the chalk surface is said to have been complete during the Eocene. So the first appearance of a chalk dome at low elevation would have been it’s last… as weathering and erosion immediately set to work denuding rock layers.

There is a gap in deposition between the Cretaceous Chalk and overlying Tertiary deposits. Such geological gaps are known as unconformities. This one shows extensive erosion took place of overlying chalk layers before the next rocks were laid down in the Tertiary. This unconformity is evidence that a great deal of chalk and Wealden series rocks were eroded away before younger Tertiary layers were deposited over the top. Early Paleocene uplift also allowed plenty of time for later sea level rise in the Eocene to deposit overlying layers of London Clay and other “marine” deposits across the eroded Weald.

Remember also the end of the Paleocene was a time of rapid global heating called the Paleocene-Eocene-Thermal-Maximum (PETM). This heating was possibly triggered by a massive methane burp from the widening of the Proto-Atlantic disturbing methane hydrates. The hot Paleocene greenhouse world triggered enormous tropical downpours of rainfall, likely accelerating erosion from uplifted land, despite a dense cover of lush forest.

Eocene and Oligocene: 55-23Ma: the Eocene epoch is frequently cited as a critical period of Weald uplift because sea level rise continued from the Palaeocene further submerging the Weald and depositing overlying Tertiary deposits, including London Clay, very likely over the entire Wealden anticline. The Late Eocene was also a phase of “intense” Alpine mountain building with some suggesting the peak elevation of the Chalk Dome, some 1500m (if ever that), was reached during the late Eocene.

As mentioned, several accounts strongly suggest that there had been a complete removal of the Chalk cover from the crest of the Weald dome by 40 million years ago. This would require the erosion of up to 420m thickness of Chalk plus at least 400m of the Hastings Beds from the Central Weald in the space of about 30 million years, ample time to achieve this.

Oligocene and Miocene Periods both have claims to be the top dog of Epochs responsible for Weald formation. The Oligocene experienced several marine transgressions followed by regression into brackish or freshwater environments. Importantly, the main Alpine mountain building phase also occurred during the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene. The Miocene itself was an immense 18 million year epoch during which it is widely suggested that the “Alpine Storm” of mountain building occurred, the building of the Alps!

The Miocene was the most intense folding and faulting of the Tertiary caused by the collision of the African and European Plates in addition to sea floor spreading widening the Atlantic. Nearer to home, these events are widely considered for being responsible for the folding of Mesozoic and Jurassic rocks of Southern England, like the Lulworth Crumple in Dorset, and for compressing the Weald basin structures and up-warping of the Weald Dome.

The Alpine Orogeny formed the Alps, Pyrenees and Carpathian Mountains in Europe. With the UK being over 1000 km from the collision zone, only minor structures record the orogeny. The majority of evidence comes from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic rocks of southern England, where it gave rise to localised folds and faults.

https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Plate-Tectonics/Chap4-Plate-Tectonics-of-the-UK/Alpine-Orogeny

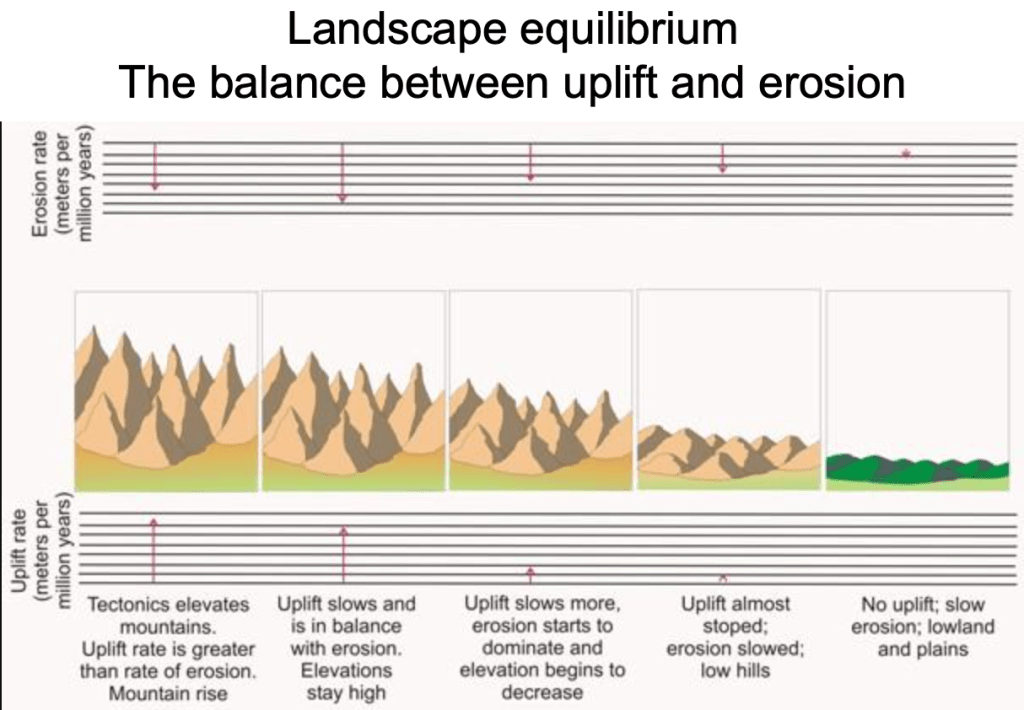

During earth moving activity, landscape formation speeds up or slows down according to relative uplift. As landscapes are forced up, denudation is accelerated as weathering rates increase with altitude, slopes become steeper and rivers erode more vigorously, incising through elevated strata to reach the new “base level”. Base level for rivers is usually sea level but local base level can also be at the confluence with a larger regional river. The base level for the Mole, for instance, is usually taken as its confluence with the Thames.

Given enough time, upland relief is ultimately lowered into a more subdued low-relief landscape, initially with isolated hills around broader lowland river valleys. This simple denudation process can be sped up or slowed down and even reversed by later uplift. Sea level change and vegetation cover will also have an impact on denudation rates, so climate is important too.

Pliocene: We finish our summary tour of Tertiary epochs in the Pliocene when further gentle folding uplifted the eroded, low-relief landscape of the Weald possibly by as much as 400m. This uplift presented the Ice Age, the Pleistocene, with the raw material ready to sculpt into the fine detailed landscape we see today.

So, newer theories suggest that there was not one single uplift but several pulses of uplift and downwarping that occurred through the Tertiary epochs with attendant relative changes of sea level. This suggests that a single large dome was probably never built and that, instead, a series of modest low-relief landscapes existed through the Tertiary. These landscapes emerged from and submerged into the sea quite frequently during the immensely long Tertiary period. This is evidenced by the existence of younger Tertiary deposits found on top of the Downs today.

The preservation of the residual soils for 60 Ma implies a land surface across much of southern England throughout the Tertiary of low elevation and low relief, except that, in the last 3 Ma it has been elevated by 250–400 m.

DCK Jones

The lowering of a landscape due to weathering and erosion is called “denudation”. For much of the time, and it was a very long time, denudation of the Weald kept pace with uplift so they balanced each other out. As uplift occurred, removal of youngest overlying rocks, like Chalk, exposed progressively older geology beneath. An obvious point is that the rocks exposed were exactly the same as today. Whilst all Wealden rocks are relatively “soft”, they have varying levels of resistance to erosion. This leads to differential erosion which, back in the Tertiary, exhumed landscapes that were probably comparable to today, with similar ups and downs of relief resulting from the same relative resistance of the same geology we have today.

Wealden Clay, for example, is impermeable and more easily eroded than resistant Hastings Beds or Lower Greensand or Chalk, so Weald Clay will always have formed lowland plains such as those found around Gatwick while more resistant Lower Greensand will always have been responsible for higher elevation land such as today’s Leith Hill which, at 294m, is the highest hill in the South East. It seems reasonable to assume that similar landscapes have repeatedly formed in the Weald over the last 60 million years.

To complicate things, the sea was never that far away and there is evidence that all or part of the Weald anticline was submerged by the sea several times during the Tertiary leading to the deposition of layers of younger sedimentary deposits over the top of the older Mesozoic Chalk and Greensand such as London Clay and Bagshot Sands.

Dynamic Equilibrium

The balance between uplift and denudation in a landscape is known as “dynamic equilibrium”. The story of the Weald landscape formation is a 60 million year battle between emergence and submergence, deposition and erosion, uplift and denudation, formation and destruction.

Over time, denuded landscapes tend to reach a dynamic equilibrium, or steady state, when erosion settles down as uplift slows. During periods of accelerated uplift, the balance may be upset causing rivers to either rapidly incise or deposit in response, a situation called disequilibrium.

As a low-relief landscape is uplifted by tectonics, erosion rates naturally increase over time in response to river channel and hill slope steepening, enhanced by increased rainfall at higher elevations. As the Weald was uplifted, denudation rates must have increased.

If climatic, tectonic and lithologic conditions are constant, a dynamic equilibrium between uplift and erosion is established, generating a steady state landscape.

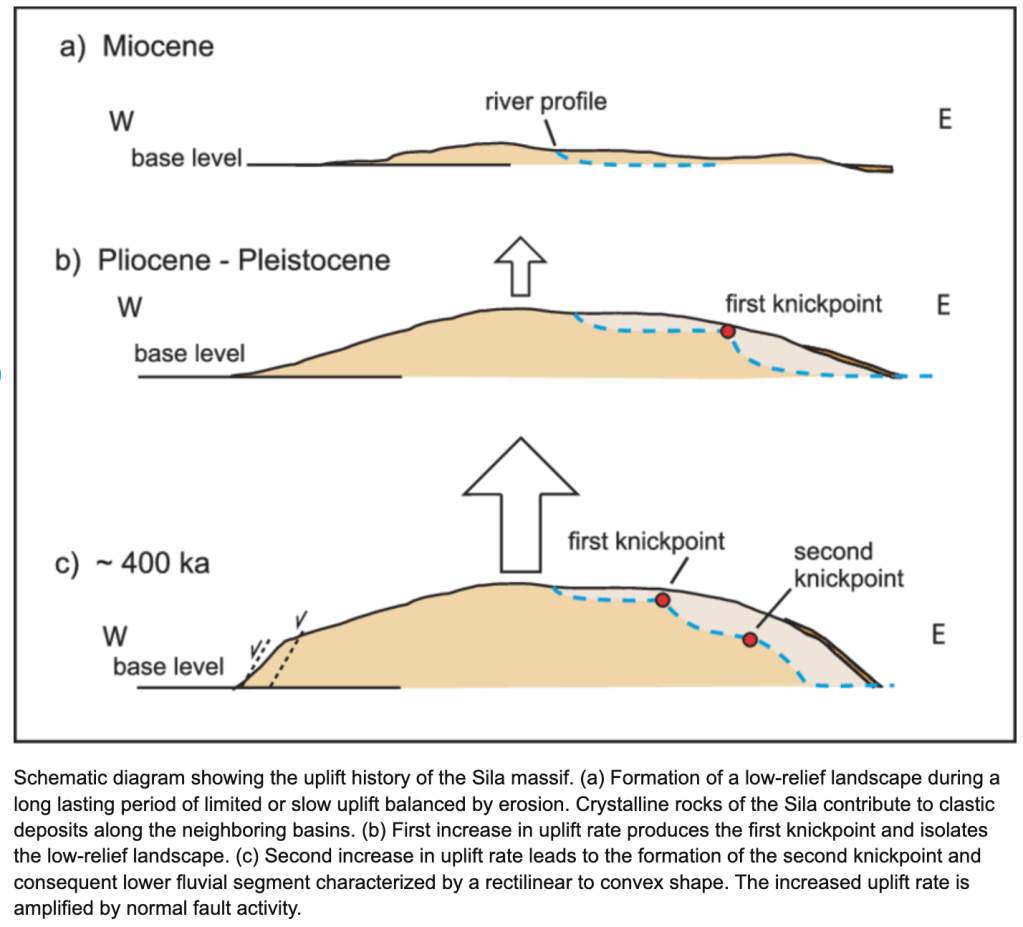

Uplift history of the Sila Massif, southern Italy; Valerio Olivetti, Andrew J. Cyr, Paola Molin, Claudio Faccenna, Darryl E. Granger

This negative feedback means despite substantial uplift causing landscape elevation is often kept in check. For example, over the last 2 million years the Sila Massif in Southern Italy has experienced rapid uplift rates of 1mm per year. Without erosion keeping pace, this rate of uplift would mean the summits should be at least twice the height of Everest (8848m) by now! Instead, the highest peak is a modest 1764m.

Rivers flowing off the Sila Massif have responded to the increasing height by furiously cutting through the landscape to reach the relatively lower base level (sea level). This means the landscape of the Sila is in disequilibrium as rivers are furiously cutting through rock, trying to “catch up” with recent rapid uplift. This is evidenced by knick points shown on the diagram below. Knick points are often waterfalls and gorges and areas of river incision and show rivers responding to lower sea levels by cutting back from new base levels. Knick poiints gradually migrate upstream through erosion.

There are knick points and even a modest gorge that have been discovered in the River Mole at Meath Green but these were not formed in the Tertiary. Instead they are relics from the Ice Age which we will cover in the next post.

So, instead of being created in one upheaval that was then eroded, rather like Michael Angelo sculpting his towering block of marble into the Statue of David, our current landscape might better be described as being gently uplifted and then “exhumed” or uncovered as overlying layers of different resistance were uplifted and then gradually removed by denudation, perhaps as an archaeologist painstakingly reveals walls and buildings by purposefully scraping away at layers they find of different hardness with their trowel.

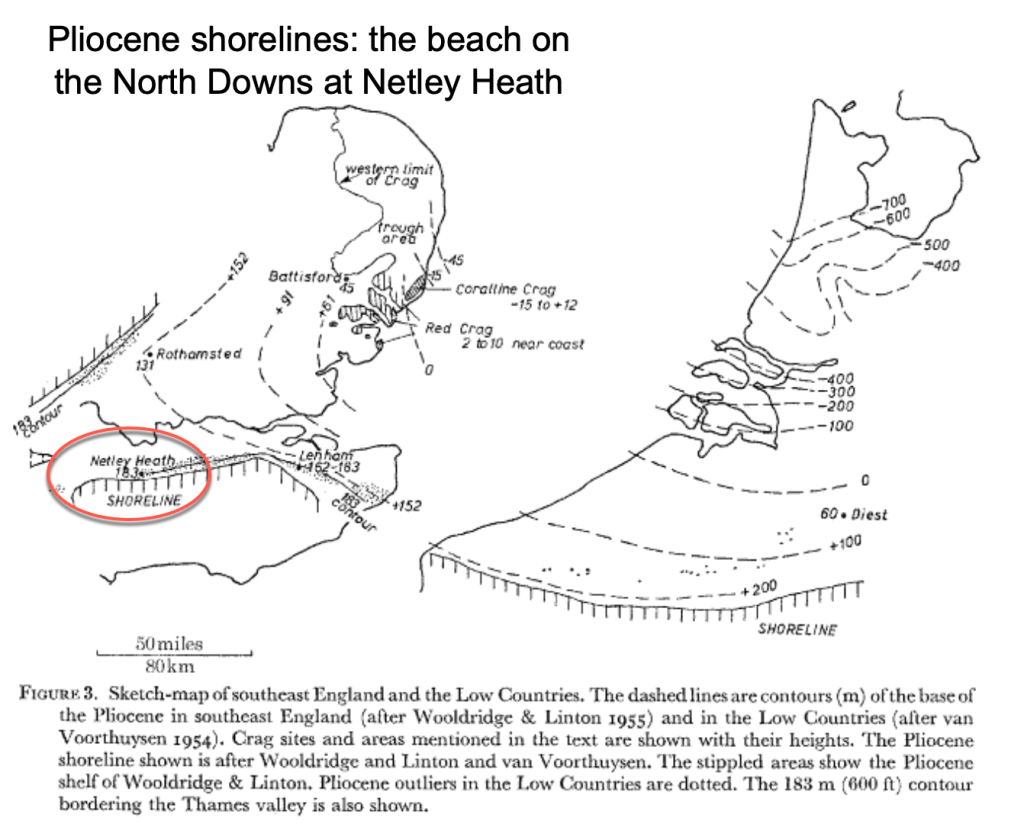

As the climate gradually cooled through the Tertiary, overall sea levels fell, a process called regression. However, there were also significant transgressions, when sea levels rose and submerged the land, in places leaving marine deposits now found mysteriously high up on the North Downs. Netley Heath “beach” deposits, for example, are found over 180m up on the North Downs near Gomshall, not far outside the Mole catchment area. I think it’s fair to say that the intriguing story behind these disturbed marine deposits, including Clay-with-Flints, has yet to be entirely resolved by geologists. Nevertheless, they illustrate the great changes in the vertical position of land and sea level during the Tertiary.

Overall, regionally, the North Sea and London Basin have both been areas of relative downwarping during the Tertiary while tectonic pulses have caused the Weald anticline to mostly rise. This explains the great thickness of London Clay found in the London Basin while none of it survives over the elevated Chalk Downs and Central Weald.

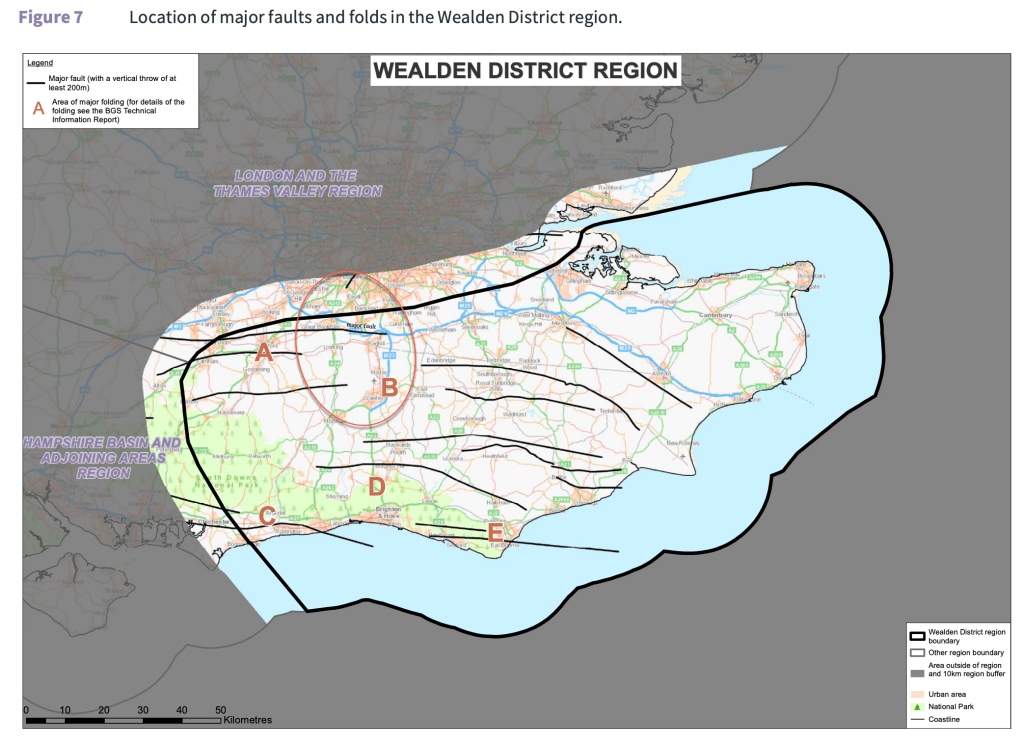

So we have to imagine slow relative changes of land and sea level: both moving up and down, the land sinking at times to meet a rising sea, and vice versa. Importantly, not everywhere in the Weald rose and fell uniformly or at the same time because the ancient faults allowed blocks of land to move somewhat independently of each other, meaning that some areas in the east of the Weald might have been completely submerged while land further west may have at times been dry land.

The point is that the 63 million year window of the Tertiary is plenty of time for sea level to change, land to rise and fall numerous times and hills to be built and eroded and uplifted again. There was no rush to create our modest landscape in one “hit” and it seems unlikely to be the result of a simple monumental event but instead a series of modest repeated events including uplift and denudation, sea level and land level rise and fall. The provenance of our beautiful hills including Leith Hill, Box Hill, Ranmore and many more, make a fascinating story. So let’s get on with some more details.

The story of the Tertiary formation of the Weald

During the Tertiary the climate was predominantly warm and humid, especially at the start, but global temperatures were overall on a downward trend to the Pleistocene Ice Age.

The Weald started off Tropical, with seasonal wet and dry seasons, for a time spiking to very hot conditions in the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum 55 million years ago (PETM in the chart above). By the end of the Tertiary, in the Pliocene, the climate was warm and temperate and dense forest covered any uplifted land. Weathering and erosion was hampered by dense forest that limited erosive runoff despite heavy rainfall. Nevertheless, time-scales were so immense that even this modest erosion kept pace with uplift for much of the time so that raised relief was probably kept “low”.

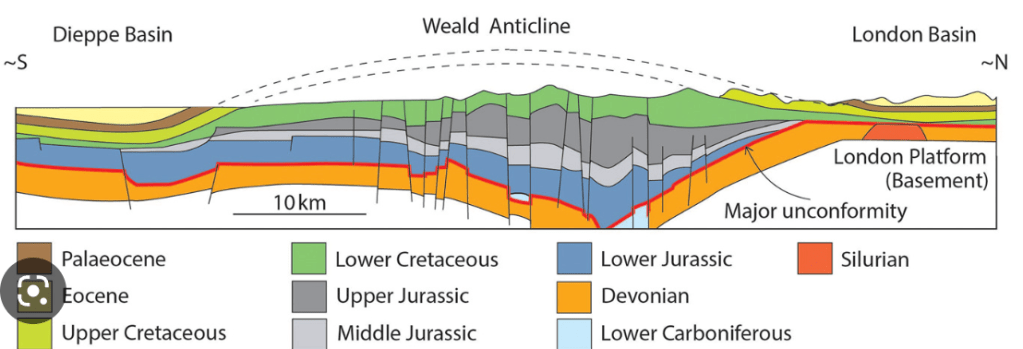

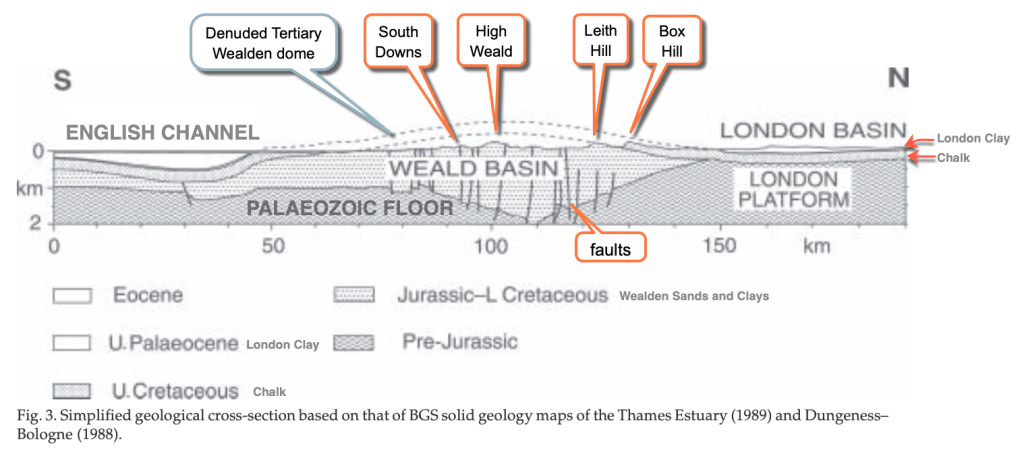

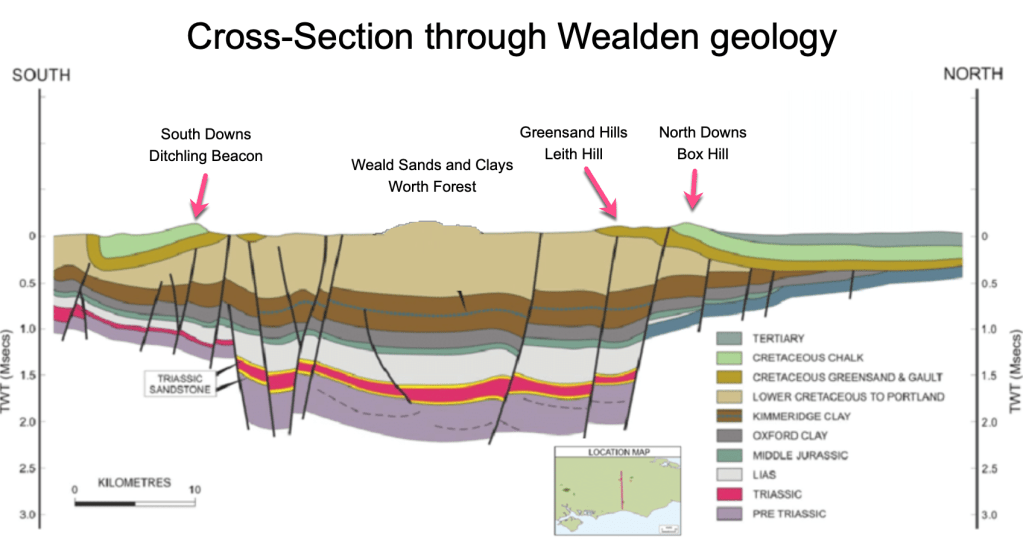

The traditional story of Weald formation, as previously outlined, tells of tectonic forces caused by the Alpine orogeny (mountain building) folding up the Mesozoic rocks into a substantial chalk dome. This was caused by the collision of the African plate with Europe which created the Alps and caused tectonic forces to compress the crust further north. In theory, given the thickness of Mesozoic deposits, the dome could have reached an absolute maximum height of 1500m if raised in one event during the Tertiary. The cross section below represents the Weald Basin and outline of the eroded dome and current profile.

However, the Tertiary timescale is so immense that a single episode raising a 1500m dome and eroding it more-or-less flat again would take a lot less than the 65 million years available even given the pedestrian erosion rates of the Weald calculated by geologists! For example, the Jura Mountains just north of the main Alpine belt, are extremely young, only 3-5 million years old. At around 1700m the resistant rocks have already undergone significant erosion. The youthful Jura mountains show how little geological time is needed to build and erode a substantial mountain range. Given the much softer rocks of the Weald it seems a single dome structure built any time during the Tertiary would have disappeared without a trace by the onset of the Pleistocene. For me, the theory of repeated phases of modest uplifts resulting in accelerated episodes of denudation and differential erosion, followed by marine transgressions of greater or lesser extent, makes more sense.

Estimations of the original thickness of Chalk (400-460m) and other Mesozoic strata indicate a complex fold structure which, if ever fully developed, would have had a summit elevation of 1400-1500m. The additional accumulation of an estimated 60-220 m of Palaeogene sediments reveals gross denudation of up to 1350m in 66 Ma or 20.4m Ma-1, a low rate on relatively erodible strata indicating periods of relative morphostasis (no denudation or deposition happening!) in the Tertiary.

On the uplift and denudation of the Weald DAVID K. C. JONES p26

So recent theories of Weald formation suggest several “pulses of uplift” happening throughout the Tertiary rather than one single big uplift. There were possibly three prominent uplift episodes in the Eocene 55Ma, another in the Miocene 15Ma and then again in the late Pliocene/ Early Pleistocene 2-3Ma. During and between times of uplift, emerging land was eroded and lowered and even submerged under sea level where fresh Palaeogene (Early Tertiary) deposits were laid down, such as London Clay.

When uplifts occurred, erosion and denudation was accelerated as relative sea level fell and rejuvenated rivers flowed off raised hills gaining energy to erode weathered material and wash it downstream into lagoons, lakes and seas. In this way, hundreds of metres of the crest were removed. The first layer to be removed from the crest was several hundred metres of Chalk, followed by progressively older layers of Wealden Sandstones and Clays.

My sketch diagram below is an interpretation of key landscape forming processes in the Tertiary. I’ve chosen the Miocene-Pliocene for the maximum dome elevation of 1500m but this is diagrammatic and, as explained, seems less likely than a series of modest uplifts.

Mechanism of Tertiary Uplift

Tectonic forces started influencing landscapes in the Southern England in the Late Cretaceous and in “pulses” throughout the Tertiary. Compressional forces creating the Alps also had distant effects in the Weald. These effects rumbled along through the Tertiary probably reaching a peak in the Late Eocene with significant further uplifts in the Miocene and Late Pliocene. However, there are debates about how far the Alpine Orogeny alone was responsible for building the Weald as Goudie et al state here:

Widespread faulting occurred, frequently rejuvenating pre-existing

Migoń, P. & Goudie A., Pre-Quaternary geomorphological history and geoheritage of Britain.

ancient structures and causing broad warpings of the crust. However, it is not entirely clear that these foldings, faultings and warpings necessarily have an ’Alpine’ pedigree. As Anderton et

al. (1979, p. 255) suggest: They could reflect crustal readjustments following the Palaeocene departure of Greenland due to sea floor spreading. In any case, “Alpine” effects in Britain were probably magnified as a result of early Tertiary Atlantic opening.

Whether the earth moving force was Alpine or sea floor spreading, the compression of the Weald Basin caused an uplift of the overlying Mesozoic sedimentary rocks (Chalk, Greensand, Weald Clay etc) forming an anticline.

The up-folding of rock structures formed in a basin is known as “tectonic inversion”. This involved compression reversing the original faults in the Palaeozoic Floor so that overlying rocks were squeezed up into a warped dome. A dome overlies the ancient hidden downwarped basin, hence the idea of inversion.

The burden of the Mesozoic rocks on the Palaeozoic Floor was so great that the ancient basement rocks had sagged along the Variscan faults. Importantly, these ancient faults aligned east-west along the axis of the Weald basin so that the dome was uplifted along an East-West ridge axis, at times forming a continuous ridge all the way to France called the Weald-Artois Anticline.

Compression shortened the crust across the basin, squeezing the overlying Cretaceous strata, reversing the faults and folding the basin rocks up into an anticline. An anticline is an arch-shaped fold where rocks get older towards the middle.

You can see the “inversion” in the cross-section above showing the sagged Weald Basin structure surviving in the Palaeozoic rocks and the overlying anticline in younger Cretaceous rocks. If you look to the North (right hand side of the diagram above) you can also see the London Basin, an old part of the relatively stable crust of the Brabant High which sagged in the Tertiary along with the rest of the North Sea, forming the Clay Sea. This subsiding stable slab was left relatively undisturbed by the folding isolated by the Weald Basin: which perhaps acted as a soft “crumple zone” for Alpine compressive forces, so to speak.

So the coincidence of the alignment of the Variscan faults and the Weald basin axis and the axis of the Tertiary dome uplift, has made geologists think the landscape of the Weald has more to do with ancient faults than Alpine folding alone.

“..the lines of small surface folds (the Greensand Hills and Chalk Downs), are now interpreted as drape structures developed over major faults in the Mesozoic strata which, in turn, pass downwards into southward inclined thrusts in the Variscan Basement”

In this final section of the post I’ll revisit each period of the Tertiary to further pin down what happened to the landscape in the Mole catchment.

Early Tertiary: Palaeogene 23-65Ma

Deposition of Chalk ceased around 70 Ma. This was due to uplift of the crust in Southern England which occurred in sporadic pulses starting in the late Palaeocene and going on to the Late Eocene and Miocene. At the same time the London Basin subsided to the north and, with rivers carrying eroded debris, this became a depositional basin known as the Clay Sea. For much of this time the central Weald was emergent and any exposed Chalk was quickly eroded.

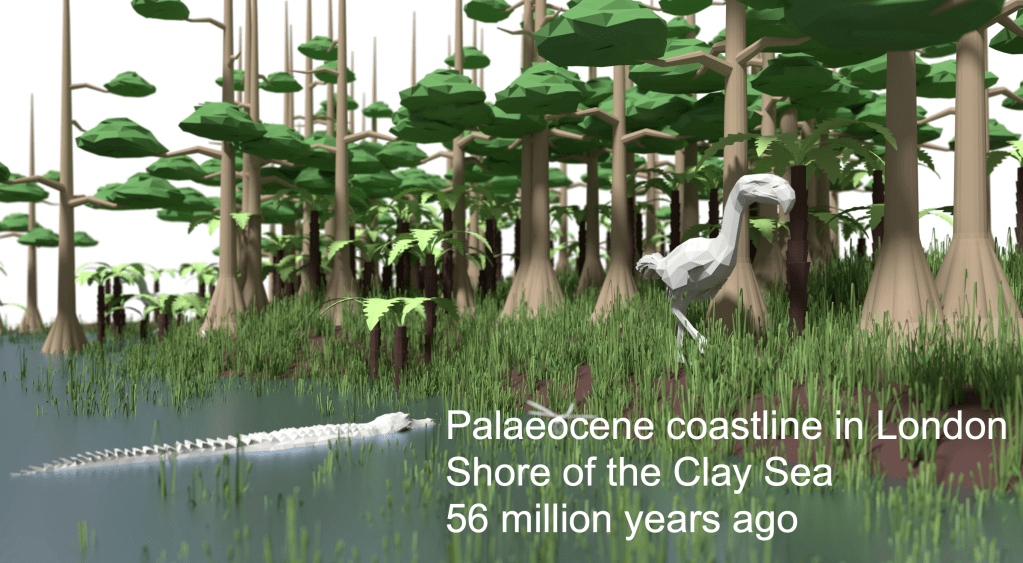

For much of the first 10 million years of the Tertiary, called the Paleocene, the entire South East of England was covered in the Clay Sea and had a substantial covering of clay, predominantly London Clay, deposited by the time it receded.

The London Basin was an area of subsidence through most of the Tertiary but, not far south, the Weald slowly became an area of uplift along the developing axis of the Weald-Artois anticline. Land that first appeared above the waves was probably a very muddy wet low relief landscape. The mud, clay and sands were washed by rivers, including a Proto-River Thames, into the Clay Sea.

A Palaeocene shoreline was discovered 33m under London during the building of HS2. The black clay rich layer was named Ruislip Beds and forms part of the London Clay formation.

“(The shoreline) would have been formed during the Palaeocene period, which was a time of intense change, with new animals evolving following the extinction of the dinosaurs. Most of Southern England was covered by a warm sea between 50 and 58 Ma and this clay helps us to pinpoint where the variable coastline was.”

https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2018/03/19/workers-discover-ancient-coastline-in-west-london/

It’s uncertain how much of the Weald emerged above the Clay Sea in the Early Tertiary but the London beach suggests that parts of the Weald were certainly land for a time. Moreover, there are Early Tertiary river, marine and lake deposits now found on top of the North Downs up to 180m aod.

In the Mole catchment, for example, the Thanet and Lambeth clays, sands and gravels lie on top of the Chalk and are found as high up as 180m on Nower Wood, Headley Heath and Burgh Heath. They were deposited in estuaries or on the shore of seas and lagoons. These deposits show that sea levels were higher than now and the area had yet to be substantially elevated. Subsequent uplift and regression of the sea meant these patchy deposits are the sole survivors of more extensive coverings.

By the Late Palaeocene and Early Eocene 56 Ma, the basic pattern of Britain’s major rivers, flowing from highland west to lowland east was set. Many of them flowed into the Clay Sea which, in the Early Eocene, still submerged much of the Weald.

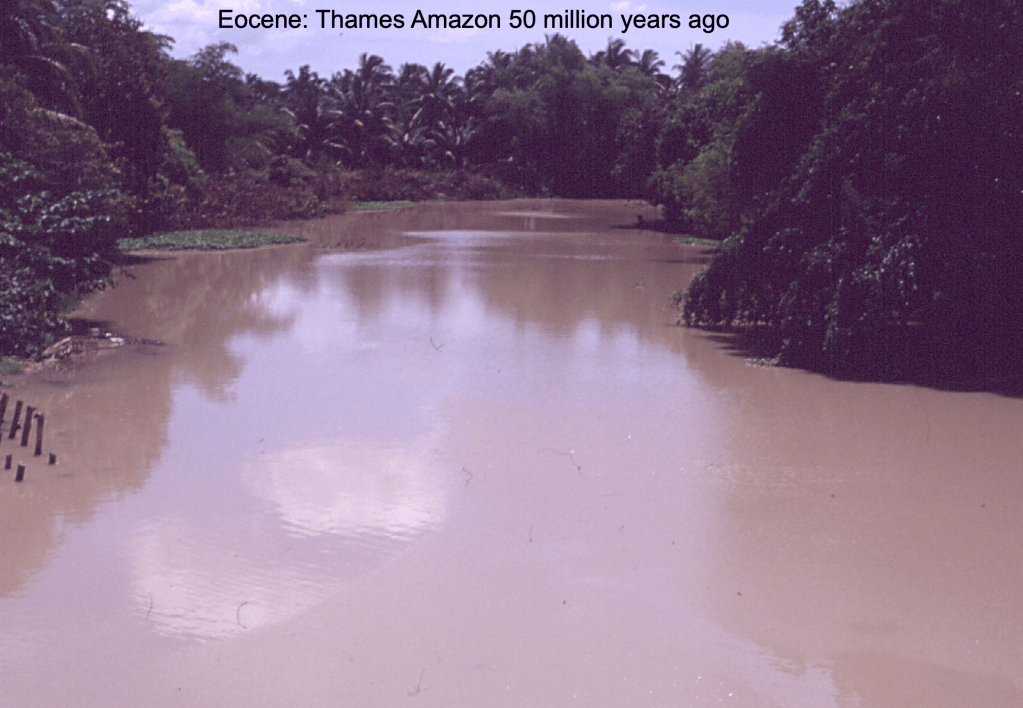

In the humid Tropical climate of the time, deep chemical decomposition of rocks was the predominant form of weathering. Long periods of chemical weathering created a thick weathered mantle. Rivers washed this clay debris into mangrove swamps and deltas around lagoons and seas. This included a Proto-River Thames which has been named the “Eocene Amazon”. The London Basin accumulated 280m thickness of clay by the end of the Eocene.

Later in the Eocene, the Weald emerged from the Clay Sea probably as isolated hills.

(In the Thames Basin) …at least 5 transgression-regression cycles are represented in the Eocene, reflecting periods of sea-level rise followed by shallowing and coastline progradation.

https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/tertiaryrivers/earlyeo.html

The Early Eocene was very warm, occasionally hot. Swathes of tropical forest covered the land around the estuaries, similar to Southern Thailand now. Rocks were subjected to chemical weathering and were then eroded by rivers as evidenced by Lower Greensand debris (resistant chert) found in Eocene sediments in the London Basin.

“…various lines of evidence point to the existence of a well developed Weald upwarp in the Early Tertiary and significant, if not total, removal of the Chalk cover from the crest of the (Central) Weald upwarp by the Eocene.”

On the uplift and denudation of the Weald DAVID K. C. JONES

Further evidence points towards the Early Tertiary uplift of the Weald occurring in pulses that lasted about 1 million years causing at least 100m of uplift on each occasion. These were accompanied by rapid erosion and sedimentation in the surrounding basins of the Clay Sea… so it’s likely the Weald never reached it’s ultimate 1500m height as pulsed uplifts were constantly being eroded to prevent land reaching higher elevation: dynamic equilibrium!

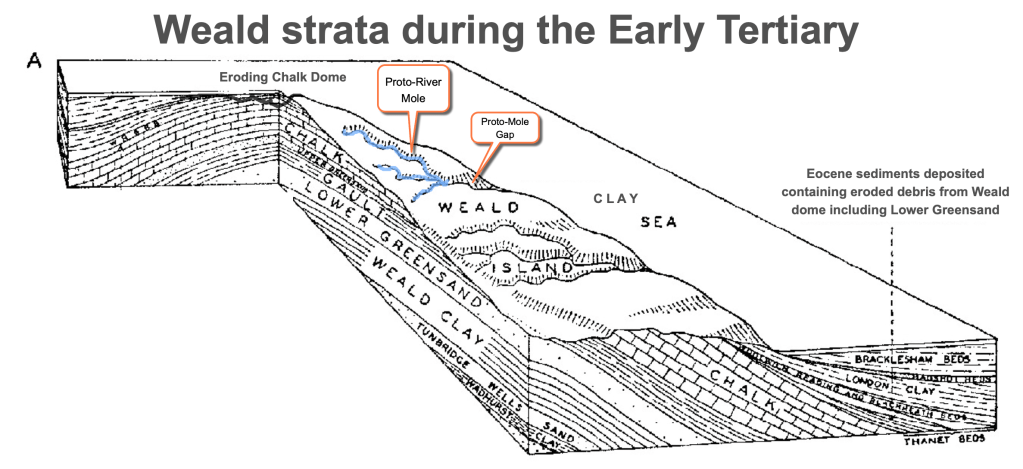

As shown in the diagram below, it’s possible that early versions of the Rivers Mole, Wey and Medway flowed off the emerging hills, eroding valleys and carrying sediments into the Clay Sea to be deposited in the London Basin. So we can imagine the very earliest River Mole eroding chalk and sandstone hills 55 million years ago, carving valleys similar to the Mole Gap now. Estimates vary but over 400m of chalk is likely to have been removed from the crest of the dome by the end of the Early Tertiary. In addition, several hundred metres of Hastings Beds and Wealden Clay must also have been removed.

Sedimentation of surrounding basins stopped in the Oligocene 23-33 Ma and in the Late Tertiary, from around 20Ma, during the Miocene and Pliocene (23-2.6 Ma), the Weald experienced further tectonic uplifts.

Late Tertiary: Neogene 2.6-23Ma

The Miocene experienced the “Alpine Storm” which is a period associated with the most intense Alpine mountain building. Many geologists think this was a time of further uplift in the Weald matched by down-warping of the London Basin.

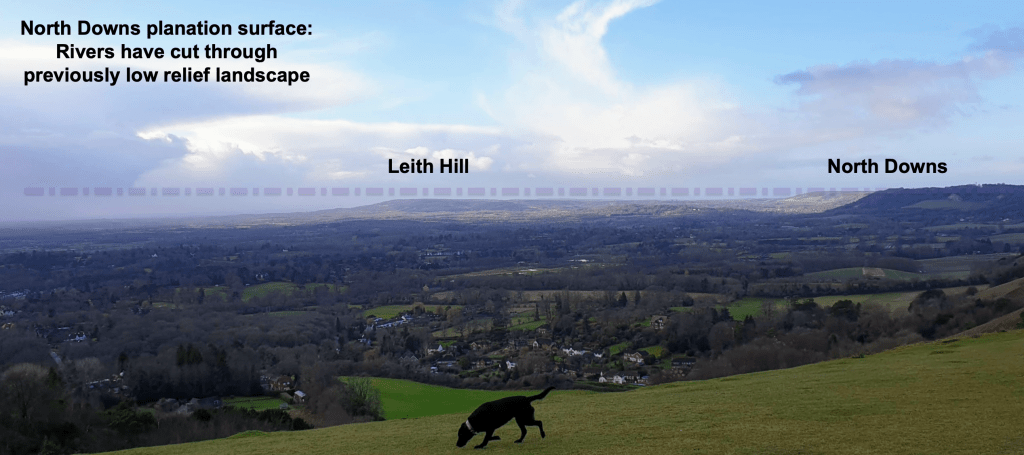

The raised hills of the Weald would have been vegetated with tropical forest slowly transitioning to a warm temperate forest by the Pliocene. By this stage it’s possible the Wealden dome comprised of hills planed off by weathering and river erosion, perhaps looking like the scene below.

During this time the Weald was part of an elongated ridge extending into Northern France. The whole ridge was called the Weald-Artois anticline and formed a continuous land bridge across to France. River drainage lines off the Weald developed during this time, including a version of the River Mole.

Near the end of the Pliocene (3Ma) it is likely the Weald had been eroded to a low relief hilly plain with few of the scarps we see now. The undulating plain would have been on average around 100m higher than now and highest in the centre of the Weald over the Hastings Beds (Worth) and the Greensand hills ridge, which may have been higher than the Downs and connected to them with a single slope to the London Basin i.e. not much of a chalk scarp yet. However, with lower land elevation relative sea levels were at times very high.

A brief period of high sea levels during the Pliocene is shown by sparse evidence of coastal gravel deposits now found on the top of the North Downs from this period. An example local to the Mole Catchment is Netley Heath marine sands and gravels, known as a “beach deposit”.

At the end of the Tertiary much of the Chalk slope was probably covered in a significant layer of Tertiary deposits like London Clay deposited earlier in the Tertiary. In addition, and even higher up on the Downs, there are also sands and gravels of “marine or estuarine origin” (with marine fossils) such as at the Netley Heath, now found 183m aod on the North Downs.

Such deposits may have provided the Chalk with a protective cover from weathering but they also show how the relative level of land and sea can change dramatically to form “marine” deposits so high up on the Downs.

The exact formation of the Netley Heath beach deposit is much debated with some geologists proposing they are a combination of marine deposits and debris washed down onto the Chalk from higher slopes of the Greensand Hills by the end of the Tertiary and further disturbed by cold-weather processes through the Quaternary.

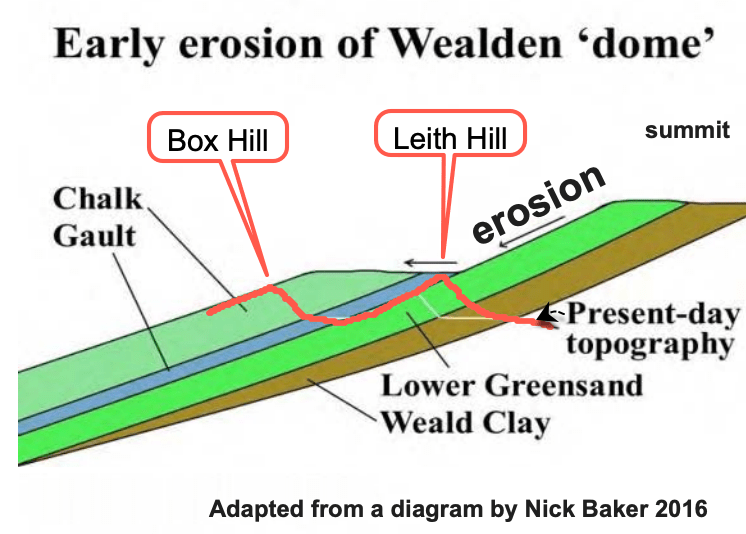

Nick Baker’s theory suggests that during erosion of the “dome”, the Chalk adjoined the more resistant Greensand forming a single slope down which older Greensand material could be derived as there was no escarpment or Clay Vale at the time. To quote directly from his essay:

…the material at Netley Heath is definitely not in-situ (formed in place). Interestingly, examples of Lower Greensand ironstone and sandstone can be seen only a few metres from the Netley Heath ‘Crag’. All of this material, both older and younger than the Chalk, is lying on top of Chalk. While the Wealden Dome was still being eroded, beds older than the Chalk could still be at higher altitude than the Chalk on the eroding slopes.

Nick Baker 2016: The Problem of Post-Cretaceous Drift Deposits

An added complexity is the existence of Clay-With-Flints which are probably older deposits found widely in our area laid on top of the Chalk Downs plateau on Box Hill and Ranmore Common. The Geology map shows them laid on the flat hill tops but neatly removed from dry valleys, the formation of which must post-date Clay-With-Flints, most probably during the Pleistocene. The British Geological Survey lexicon states that Clay-With-Flints is a range of “residual” clays, sands and gravels which may have formed any time between 23.03 million and 11.8 thousand years ago during the Neogene and Quaternary periods. This 20 million year window suggests a lot of uncertainty surrounding how this deposit got onto the Downs and, once there, how it survived the rigours of 20 million years of uplift, submergence and denudation. It’s especially difficult to explain when Netley Heath deposits are found very close to Clay-With-Flints on the North Downs.

Let’s recap the story so far using this amazing diagram from DCK Jones:

The cross-section diagram above, adapted from DCK Jones 2016, shows the denudation (erosion) of the Weald Dome since uplift in the Early Tertiary.

The diagram might appear to support the single Dome uplift and subsequent denudation theory but what it really shows is the estimated thickness of rocks that “needed to be removed” to exhume the landscape of today. For example, geologists are pretty sure there was a coverage of at least 400m of Chalk laid down across the top of the Weald by the Late Cretaceous. After uplift, erosion would have removed some (or all!) of the youngest Chalk. By the Early Eocene 55ma there is known to have been a Clay Sea where further marine Palaeogene deposits were laid down over the Chalk (e.g. London Clay, possibly including maybe Clay-with-Flints or similar). The Jones diagram above shows the thickness and sequence of rocks that needed to be sequentially removed or added to reach our current landscape. The absolute height of these surfaces is not certain and, in any case, both sea and land levels changed a lot during the Tertiary so a single absolute altitude scale is not going to tell the entire story.

Starting from the oldest layer at the bottom: the diagram shows the Palaeozoic Floor, now buried over 1km below the South Downs, dipping to 1.6km below the crest of the Weald before rising abruptly beneath the North Downs and London to form the London Platform. The London Platform was a stable block that was responsible for providing a source of the immense thickness of sediments that built up in the Weald Basin during the Jurassic and especially the Cretaceous. The steep rise in the Palaeozoic Floor under the North Downs is related to the northern limit of mountain folding associated with the Variscan Front. The London Platform became a buffer zone against which folding up of the Weald anticline occurred. The steeper gradient of the North Downs dip slope, compared to the South Downs, is testament to this deep resistant foundation.

There are three numbered locations shown on the diagram that refer to the Mole Basin:

- The total thickness of chalk strata is highest over the Central Weald where it is exceeds 400m. Chalk strata then decreases away to the North and South Downs, though it increases in the Channel basin. Beneath the Chalk, there is an enormous thickness of Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks which is again greatest in the Central Weald Basin at over 2km in total. A total lowering of some 1200m occurred in the Central Weald to reach the current landscape profile over the Worth Forest.

- The shape of the dome shows a steeper gradient descending on the north slope, towards London, than the south slope towards the Channel. The steeper incline is suggested due to the buffering of tectonic forces during the Variscan Orogeny against the stable London Platform. Over Leith Hill some 600m of lowering has occurred to reach the current summit, involving mostly the removal of Chalk. This puts the theoretical absolute max height of Leith Hill at around 900m, if a dome ever existed. But did it? Was Leith Hill ever 900m in height, similar to a substantial Scottish mountain today? Or, as has been proposed, were repeated pulses of tectonic uplift and denudation more likely to be the story?

- Interestingly, the steep slope and the relatively thick Palaeogene deposits over Box Hill, laid down after and on top of the Chalk during the Early Tertiary, suggests surface lowering on the Chalk Downs has been least and slowest of all our hill tops since uplift. The removal of some 300m of Palaeogene deposits was estimated to reach the Chalk by the start of the Quaternary, just 100m above the current profile. This shows that, of all the local landscapes, the North Downs have been least lowered since the start of the Pleistocene. However, weathering and erosion still had a major impact shaping the Downs by modifying and carving deeper Gaps and Dry Valleys in the Downs. Actively “decorating” the Downs with the features we see today.

From these figures, the average denudation rate for the Central Weald is around 20m of rock removed per million years (m/Ma) and for the North Downs this declines to 8m/Ma. Remember the Sila Massif in Italy? It has risen by a rate of 1mm per year over the last 2 million years. If we convert to the same units, the equivalent Wealden denudation rate is 0.02 mm per year, incredibly slow, geologically speaking.

As D Jones suggests these are “exceptionally low mean denudation rates indicating (their) plausibility”. Rates may have gone up at times, in particular during the very active phase of the Pleistocene, but would be much lower at other times, for example under the dense forest canopy of the Early Tertiary. Returning to our first idea… the Weald landscape through the Tertiary was subjected to several pulses of uplift which were met with resultant increases in denudation…a broad state of dynamic equilibrium. Everything occurring at a geologically pedestrian rate! This steady-state equilibrium would be seriously upset in the next part of our story … the Pleistocene Ice Age!

The Pleistocene is a relatively short span of just 2.6 million years when colder climates meant weathering and erosion rates were at their greatest at any point in the prehistoric formation of the Weald.

References:

Wealden District Regional Geology : Radioactive Waste Management https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/834550/Wealden_District_Regional_Geology_V1.0a.pdf

History of the major rivers of southern Britain during the Tertiary Compiled by Philip Gibbard & John Lewin https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/tertiaryrivers/

D K C Jones London School of Economics: The Weald p73-101 A. Goudie and P. Migoń (eds.), Landscapes and Landforms of England and Wales, World Geomorphological Landscapes,

Nick Baker 2016: The Problem of Post-Cretaceous Drift Deposits https://mfms.org.uk/pages/pdf/Muck%20notes.pdf

Pliocene beach under London https://www.archaeology.wiki/blog/2018/03/19/workers-discover-ancient-coastline-in-west-london/

Hansen, D.L., Blundell, D.J. & Nielsen, S.B. 2002–12–02. A Model for the evolution of the Weald Basin. Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, Vol. 49, pp. 109–118. Copenhagen.

South East Research Framework Resource Assessment and Research Agenda for Geology and Environmental Background (2018 with additions in 2019)Geological and Environmental Background Martin Bates and Jane Corcoran

Migoń, P. & Goudie A., Pre-Quaternary geomorphological history and geoheritage of Britain. Quaestiones Geographicae 31(1), Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań 2012 https://sciendo.com/pdf/10.2478/v10117-012-0004-x

British Geological Survey: Geology Viewer and Lexicon https://geologyviewer.bgs.ac.uk/?_ga=2.7037298.1327190817.1675929737-1868444071.1675929737

Mole Valley Geology Society https://www.mvgs.org.uk/geomorphology

How Britain Became and Island: Lecture with Professor Phil Gibbard. https://www.qpg.geog.cam.ac.uk/research/projects/englishchannelformation/

Variscan Orogeny https://variscancoast.co.uk/variscan-orogeny

The Geology of the Weald. William Topley FGS. Published HMSO 1874

Relative Land-Sea-Level Changes in Southeastern England during the Pleistocene, Vol. 272, No. 1221, A Discussion on Problems Associated with the Subsidence of Southeastern England (May 4, 1972), pp. 87-98 (12 pages) R. G. West Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences

Leave a comment